At a Crossroads in 2026: The Independent vs Corporate Dilemma

Consolidation Hits Home

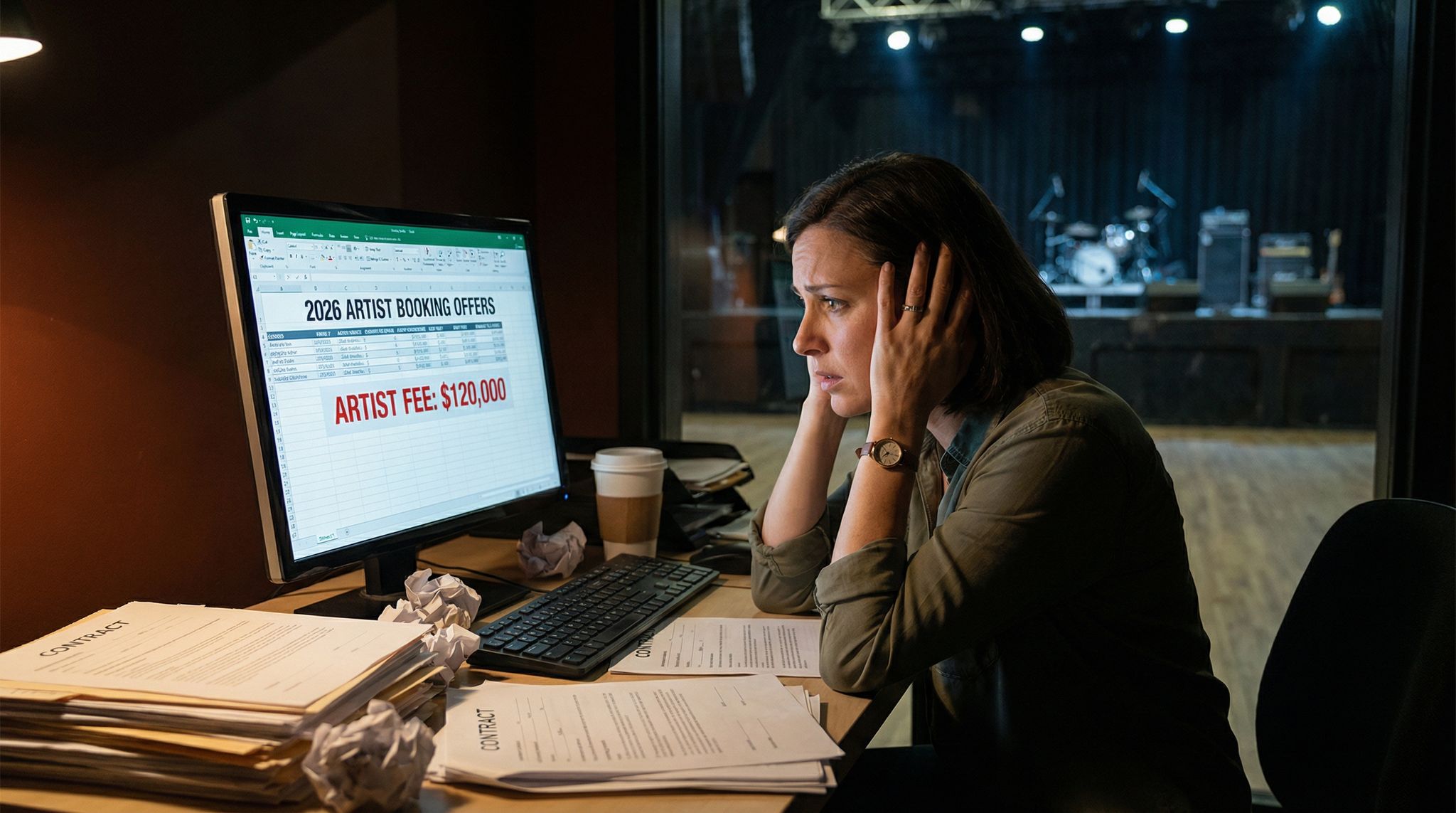

Live music is booming again in 2026, but venue owners face a pivotal choice: stay independent or join forces with a corporate giant. The industry has seen dramatic consolidation – global promoters like Live Nation and AEG now control a huge share of venues and tours. In the U.S., Live Nation’s merger with Ticketmaster has given it what senators call “monopoly-like control” over many venues, a concern highlighted during Senate hearings on Live Nation’s market dominance. Meanwhile, independent venues are struggling post-pandemic; one survey found 64% of indie venues were financially unstable heading into 2026. The UK’s Music Venue Trust reports that rising costs squeezed grassroots venue profit margins to near zero (just 0.2% on average) and a quarter of UK clubs have closed since 2020. These sobering stats underscore why buyout offers are landing on owners’ desks.

Yet consolidation isn’t total. In every country, some venues fiercely guard their independence. Organizations like the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA) in the U.S. and the Music Venue Trust (UK) rally to support local venues with grants and lobbying, such as the $16 billion Save Our Stages fund in the U.S. that saved many clubs. Corporate promoters are expanding aggressively, but communities are pushing back in spots – new Live Nation venue projects often meet local resistance from those wary of chain venues. This collision of trends puts many venue operators at a crossroads.

The Stakes: Culture vs Capital

The decision to “sell out or soldier on” will reshape a venue’s future in profound ways. An owner of a beloved 500-capacity club might be offered a lucrative buyout by a big venue network promising renovations and a pipeline of major artists. It’s tempting – especially when independent finances are precarious – but it also raises fears of losing the venue’s soul. Fans and artists often see independent venues as cultural havens. As one Nashville musician warned, when indie spots get “homogenized and corporatized, focusing on profit… the character and tastemaking… disappear”, leading to a loss of authentic connection and passion. In other words, cleaner bathrooms and bigger budgets might come at the cost of the quirky charm and community feel that made a venue special, a sentiment echoed by financially vulnerable independent music venues.

On the flip side, saying “no” to a buyout means betting on yourself to survive in an increasingly competitive market. Independent venue owners must consider if they can continue to finance improvements, attract big acts, and withstand economic blows without a deep-pocketed partner. In a crowded live entertainment scene, indie venues have to work smarter to stand out. Many succeed by carving out a unique niche and loyal community – for example, venues like London’s 100 Club (founded 1942) leverage their rich history and aura no modern venue can manufacture to compete against newer corporate-owned venues. The decision is deeply personal and situational. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer – only a careful weighing of pros, cons, and the venue’s core mission.

Turn Fans Into Your Marketing Team

Ticket Fairy's built-in referral rewards system incentivizes attendees to share your event, delivering 15-25% sales boosts and 30x ROI vs paid ads.

(In the sections below, we’ll dissect both paths – the promise of corporate backing and the pride of independence – with candid advice and real-world examples to help you make an informed choice.)

The Lure of Corporate Backing: What Selling Offers

Capital Infusion and Financial Security

For many venue owners, the biggest allure of a corporate partnership or sale is financial relief. A buyout can wipe out debts, fund major renovations, and provide the capital to upgrade everything from sound systems to seating. Corporate operators often promise to “take the venue to the next level” with significant investments. For instance, when Live Nation took over operations of Bangkok’s Impact Arena, it announced plans for improved hospitality facilities and upgraded concessions. Such capital projects would be hard to afford for an independent. In Denmark, the 17,000-seat Royal Arena is being acquired by Live Nation with a pledge to modernize amenities and even add renewable energy infrastructure like solar panels and battery storage systems. Access to deep pockets means critical upgrades (new HVAC, more seating, LED walls, etc.) can happen immediately rather than in phases over years – potentially boosting the venue’s competitiveness and safety at a stroke.

Financial backing isn’t just about improvements; it’s also about stability. Corporate-owned venues have a cushion during downturns. If ticket sales dip or an expensive show flops, a parent company can absorb the loss across its portfolio. Independent venues have no such safety net – one bad season can threaten their survival. The corporate support extends to big crises too. During the pandemic shutdowns, some venues owned by large firms managed to weather closures more easily (with corporate reserves or restructuring) while independent venues had to rely on government aid and crowdfunding to hang on. In essence, being part of a conglomerate shares the financial risk. An owner who sells may trade solo ownership for peace of mind that the lights will stay on even in tough times.

Touring Network and Talent Access

Another advantage veteran operators cite is plugging into a powerful booking and marketing network. Corporate promoters control many artist tours and ticketing platforms, which can translate into busy calendars and bigger acts for their venues. For example, an independent theater that joins a major promoter’s venue family might suddenly find it’s on the routing list for top touring artists it couldn’t land before. Large companies can route their artists through owned venues as a priority, ensuring those stages get marquee shows. They also often bundle venues into tour deals – e.g. an artist might sign a tour contract that includes multiple Live Nation venues in different cities. If your venue is one of them, you benefit from that steady pipeline of talent.

Marketing muscle is part of this equation. Corporate operators have dedicated marketing teams and data-driven promotion strategies that individual venues struggle to match. They maintain huge databases of concertgoers and sophisticated CRM systems to boost ticket sales. By selling or partnering, an independent venue gains access to these centralized resources – from nationwide email marketing blasts to cross-promotion on Ticketmaster’s platform. The venue might also appear in membership programs or festival tie-ins that a big promoter runs, further raising its profile. In short, corporate backing can greatly amplify a venue’s reach: your shows show up in more apps, more advertising, and more tour announcements than if you were going it alone, helping you stick to your venue’s story and brand.

There’s also a human element: established promoters have relationships with agents and managers that span decades. When your venue is under a respected corporate umbrella, agents may be more confident to route their mid-level or rising artists there, knowing production standards and payments are guaranteed by a larger entity. This can be especially helpful for venues in secondary markets that historically struggle to book major talent. In 2026’s competitive booking landscape, being part of a big network can open doors – one reason some small-market venue owners sell is to get on the radar for bigger tours. The trade-off, as we’ll see, is that you might lose some say in which artists come through (booking could be more centrally managed), but the volume and caliber of shows often increase under corporate management.

Data-Driven Event Marketing

Track ticket sales, demographics, marketing ROI, and social reach in real time. Exportable reports give you the insights to make smarter decisions.

Operational Support and Upgraded Tech

Running a venue involves countless operational challenges – another area where corporate ownership promises relief. Major venue companies bring in professional management systems, bulk procurement, and expert staff training. They’ve refined best practices across dozens of venues, which can streamline your operations. For example, a corporate parent might introduce advanced inventory management and cost controls that immediately boost your profit margins. They also often handle HR, legal compliance, and accounting centrally. An independent owner who’s been wearing 10 different hats suddenly has a corporate support structure: dedicated marketing teams, ticketing specialists, safety officers, and more. This reduces the day-to-day burden on the local venue management, letting them focus more on programming and hospitality and less on back-office tasks.

Technology is a big part of this support. Corporate venues tend to have cutting-edge ticketing and analytics systems, cashless payment tech, and standardized event software. They can afford large upfront tech investments that an indie venue might postpone. For instance, a corporation might install a new scanning system or upgrade the venue’s Wi-Fi and RFID capabilities to enable immersive fan experiences and efficient crowd flow. These enhancements can improve customer satisfaction and operational efficiency (e.g. shorter lines, better data on attendee behavior). A concrete example is New York’s Irving Plaza: after Live Nation’s multimillion-dollar renovation, it reopened with state-of-the-art sound and lights and upscale VIP lounges. Many independent venues dream of such upgrades but struggle to finance them or execute at the same level. Selling to a company that standardizes production specs across its venues means your stage and systems get brought up to world-class benchmarks fairly quickly.

Another operational perk is economies of scale. Corporate entities leverage bulk purchasing deals for everything from beverages to lighting rigs. They might negotiate national contracts with liquor suppliers or security firms, getting volume discounts that your single venue could never secure. Those savings can improve profit margins (or allow more investment in customer experience). Additionally, corporates can share staff between venues or bring in specialized crews for major events. If your indie venue always felt understaffed for big shows, joining a larger group can ensure you have the manpower when it counts – they might send extra technicians or marketing staff for a festival night, for example. In summary, corporate ownership offers an appealing proposition: more resources, more expertise, and less reinvention of the wheel. For a tired owner who’s been figuring it all out alone for years, that can be a big relief.

Growth Opportunities and Exit Strategy

Finally, selling can unlock new growth opportunities that are hard to achieve independently. Corporations often have strategic expansion plans – if your venue has untapped potential (like extra space or a market that could support more events), they might invest in adding a second stage, opening a restaurant on-site, or transforming off-nights with new programming. An independent owner might be maxed out handling the current schedule, whereas a corporate partner can envision scaling up. We’ve seen examples of mid-size venues acquired and then expanded into multi-space complexes under corporate guidance, or small clubs that become flagships for a brand and get physical upgrades as a result. Being part of a big family can also make your venue more attractive to major sponsors and brand partnerships, bringing in extra revenue streams (e.g. a naming-rights deal or sponsored VIP lounge that an indie might not land on their own). Many large sponsors prefer dealing with a national entity for consistency, so venues in a chain often get first dibs on lucrative sponsorship packages and authentic integration opportunities.

It’s also worth noting that selling isn’t always total – some owners retain partial ownership or a management role post-acquisition. This can be a way to enjoy the best of both: you cash out a portion of your equity, reduce personal financial risk, but stay involved in guiding the venue’s direction (to an extent) and share in future success. Structuring a deal to “take some chips off the table” while remaining as a minority partner or creative consultant is common. For owners nearing retirement or simply burnt out from years of grinding, selling to a corporate operator can be a smart exit strategy. It ensures the venue will continue (under new stewardship) rather than potentially closing if you walked away without a successor. Many legendary venues have been saved from closure by being sold to larger groups that have the means to keep them alive. As we’ll explore, some have thrived in that transition. Peace of mind, legacy preservation, and financial reward are strong motivators for considering a corporate path.

(Of course, if this all sounds too rosy, it’s because we haven’t discussed the trade-offs yet. Many venues gain funding and stability when corporatized, but they sacrifice other elements that owners hold dear. Let’s dive into those next.)

The Trade-Offs: What You Might Lose by “Selling Out”

Loss of Autonomy and Creative Control

Every independent venue has its own personality – often cultivated by an owner’s personal vision. One of the hardest trade-offs in a sale is giving up full control over that vision. When you’re independent, you call all the shots: what genres to book, which local charities to support, how late shows run, what beer is on tap. A corporate parent will inevitably have a say in these decisions. Creative choices that were once based on passion might face profit-driven scrutiny. For example, you might love hosting experimental art-rock bands on weeknights even if they only draw 100 people – as an indie operator, you had the freedom to nurture that scene. Under corporate ownership, such niche bookings could be nixed in favor of reliably profitable events. A finance department might question “unprofitable” programming or demand every night meet certain sales targets.

Booking policies can change. Your new owner could centralize booking, meaning you no longer personally curate every show. The venue might be required to hold dates for the corporate promoter’s touring artists, even if you’d prefer a local showcase or a dark night. Many founders find it painful when “their” venue’s identity drifts: maybe the EDM weekly you built from scratch gets dropped because headquarters says so, or the all-ages punk shows give way to more 21+ events to boost bar revenue. As one industry guide put it, the louder the investor’s voice in decisions, the bigger the investment. Even if you stay on as a manager, you will be negotiating and compromising on decisions you used to make freely. This loss of autonomy can sting for a venue that was born from a labour of love.

Ready to Sell Tickets?

Create professional event pages with built-in payment processing, marketing tools, and real-time analytics.

Beyond booking, nearly every aspect of operations might come with corporate guidelines. You could lose flexibility in things like setting ticket prices (the parent company may mandate dynamic pricing or higher fees), choosing vendors (perhaps you must use the corporation’s preferred security company or a sponsored soda brand), or even decorating the space. Corporate branding might appear on your venue’s signage and website, altering its image. For venues built on a quirky or countercultural brand, “going corporate” can be more than a symbolic shift – it actively changes the atmosphere. Veteran promoters warn that big companies often sand off the edges that made a place unique. Will the dance night for the queer community or the underground metal fest still fit your new owner’s brand standards? There’s a real risk of mission drift: your original goals get diluted as the venue becomes one cog in a big machine, potentially losing the mission to elevate culture.

Brand Identity and Fan Perception

Independent venues often enjoy a special rapport with their audience. Regulars and local musicians feel a sense of ownership and pride – it’s “our spot”, a home for the scene. Selling to a corporation can jeopardize that goodwill. Fan and community backlash is a known phenomenon when beloved indies “sell out.” Core fans might react with skepticism or disillusionment, fearing that the venue will lose its magic. We’ve seen examples of this: when a formerly indie festival or venue announces a buyout, social media often lights up with laments about “the end of an era.” It’s not just sentiment; loyal customers may genuinely change their behavior if they feel the venue’s vibe has changed. As one NPR interviewee put it, music lovers dread a world where all the intimate, unique spaces get homogenized and corporatized, focused only on profit, leading to a loss of character and tastemaking.

A venue’s brand identity can shift overnight with a corporate logo on the marquee or new rules in place. If your venue was known for its indie credibility or community ethos, a sale might undermine that branding. For instance, a club that prided itself on being a grassroots, DIY space could look hypocritical to some fans once it’s under a conglomerate (no matter how well-intentioned the sale). In practical terms, audiences might notice changes like higher ticket/service fees, more sponsor advertising around the venue, or stricter policies – and they’ll attribute it to “corporate influence.” True or not, the perception can hurt the venue’s cachet. Community relationships might also be tested: local arts councils or neighborhood groups who supported you as an indie venue may worry a corporate owner will be less responsive to local concerns (like noise, charity events, youth programs, etc.). Maintaining community trust requires careful communication. Bonnaroo, for example, made a point under Live Nation’s ownership to involve fans in surveys about the festival’s direction to show that their voices still matter. Not every corporate takeover makes that effort.

There’s also a risk of the venue becoming generic. Independent venues often develop a distinct character over years – whether it’s the graffiti on the walls, the way the staff interacts like family, or the traditions like an annual locals-only showcase. Large operators strive for consistency and efficiency, which can inadvertently strip away some of that character. One touring artist compared it to radio stations after conglomerates took over: “the bar food might be better, but the character … disappears”, as noted in a report on financially vulnerable venues. Fans might find the new experience a bit more polished but a bit less special. For owners who spent decades building a brand, this can feel like seeing your “child” change under someone else’s parenting. It’s a trade-off that weighs heavy: is the financial gain worth the possible loss of your venue’s identity? Many veterans caution to think about your legacy – once a venue’s culture is altered, it’s hard to reverse.

Corporate Policies, Bureaucracy and Constraints

When you join a corporate structure, you invariably take on layers of bureaucracy and policy compliance that weren’t there before. Independent operators revel in their agility – if something isn’t working, you can change it by next week. Under corporate ownership, decisions might need approval from regional VPs or align with national policies. This can slow down everything from booking a last-minute show to fixing a leaky roof. Need an extra bartender on a busy night? You might have to justify it to corporate finance. Want to adjust your 18+ age restriction for a special event? Check the standard policy first. These procedural hoops can be frustrating for a team used to improvising solutions on the fly. Local autonomy often shrinks; your creative solutions must fit within bigger templates.

Corporate owners also implement strict compliance regimes – which is beneficial for safety and consistency, but can feel stifling. Expect more paperwork, audits, and rules: detailed incident reporting, standardized employee training modules, precise accounting practices, etc. Safety and accessibility regulations might be enforced more stringently (again, not a bad thing, but definitely a change in day-to-day operations for a scrappy indie crew). There may be less tolerance for the kind of DIY fixes or informal arrangements many indie venues use to get by. For example, an independent venue might have a long-time volunteer doing sound on weekends; a corporate firm might require certified engineers only, ending that informal role. Uniformity becomes the goal – the venue’s operations are expected to meet the company’s brand standards in all respects.

Another constraint can be exclusive contracts and corporate deals that override local preferences. Perhaps as an indie venue you proudly served local craft beer; under a new owner, you could be contractually obligated to switch to a major beer sponsor’s products. Similarly, you might lose the freedom to choose your ticketing provider or tech vendors – most big operators have exclusive deals (e.g., using Ticketmaster for all ticketing, which might bring higher service fees or less flexibility). If the corporate parent has a national deal with a concession company, you’ll be using their menu and pricing, not setting your own creative food offerings. These changes can not only pinch the customer experience but also remove some revenue autonomy (you might get a smaller cut of bar sales if it’s run by a third-party concessionaire now, for instance). Profit priorities can also pressure the fan experience: corporate management might push dynamic pricing or VIP upsells that you avoided as an indie out of respect for your community. Attendees could see higher prices or more aggressive monetization (like more VIP areas taking up space) once growth and profit targets are set by head office.

In sum, joining a corporate operation means accepting that your venue is now part of a larger business, and will be run as such. This can be freeing in some ways (less chaos, more structure) but it can also feel like red tape for those used to indie flexibility. Many owners struggle most in the first year after a sale with culture clash – their small team adjusting to corporate HR, their informal vibe adjusting to a more professional corporate culture. Some staff may leave, not wanting to work for “the man”. As the owner, you might find yourself having to act more like a venue general manager and less like an entrepreneur. If you thrive in corporate environments, this may be fine; but if you’re a free spirit, it can chafe.

Sharing Profits and Shifting Priorities

It’s important to remember that selling or partnering means sharing the pie. As an independent, if you managed to turn a profit, that profit stayed in your business (or your pocket). With a corporate owner or investors involved, revenue now gets split. Typically, a corporate venue has to meet certain profit margin targets and a portion of profits will be taken as corporate earnings or to pay back the investment. In some deals, the original owner might retain a percentage of profits, but it will never be 100% again. Some owners are fine with this – a smaller slice of a much bigger pie (if the venue does better with corporate support) can still be an improvement. But it does mean giving up full financial upside. If a show sells out or the bar has a record night, that windfall isn’t solely fueling your next project; it’s contributing to a conglomerate’s bottom line or paying off the buyout price.

Moreover, corporate accounting might change how resources are allocated. Expenses you used to consider part of doing business (like comping local promoters a few drinks, or spending extra on a niche show marketing) could be seen as unnecessary costs when the mandate is to maximize profit. You may face pressure to cut “inefficiencies” that were actually part of your venue’s charm (e.g. reducing the hours of that personable ticket window employee in favor of online-only sales, because it’s cheaper – even if some local patrons loved the human touch). The parent company’s priorities can impact staffing levels, ticket pricing strategy, even how often the venue is rented out for private events. A venue that once balanced community events with concerts might be pushed to monetize every night, leaving less room for non-profit or community uses that don’t bring in revenue.

It’s also possible that corporate financial issues elsewhere could affect your venue. If the parent company hits a downturn, they might impose budget cuts across all venues – resulting in slashed marketing budgets or deferred maintenance at your location, decisions you have little control over. In extreme cases, a corporate owner could decide to divest or close venues that don’t meet targets. Unlike an independent owner who might stick it out through thin times out of passion, a corporation can be quick to pull the plug if returns are insufficient. This means your venue’s longevity is tied to broader business considerations, not just local support. For example, Live Nation has so many venues that it periodically shuffles its portfolio; one city’s venue might be sold off or rebranded if strategic direction changes. Job security for your staff, including yourself if you stay on, now hinges on corporate evaluations. Some veteran venue managers who stayed after a buyout note that they went from being their own boss to worrying about “making the numbers” to keep corporate happy.

In weighing a sale, it’s crucial to understand these trade-offs. Yes, you may get a big check and new resources – but you cannot put a price on independence once it’s gone. As the saying goes, “there’s no going back”. Before you sign on the dotted line, imagine your venue five years post-sale: Is it still your venue in spirit? Are you still proud of it? Or do you risk becoming a stranger in the very place you built? Those questions lead many to conclude that independence, for all its struggles, is worth preserving. Next, we’ll look at the flip side: the benefits of staying independent and how some venues double down on that path successfully.

Grow Your Events

Leverage referral marketing, social sharing incentives, and audience insights to sell more tickets.

The Case for Staying Independent: Pride and Perseverance

Preserving Creative Vision and Freedom

Independence means you are the master of your venue’s destiny. For many operators, this freedom is the very reason they got into the business. Staying independent lets you keep your creative vision pure. You decide the programming mix, the atmosphere, the causes the venue supports, without needing permission from a parent company. This creative control can be especially important if your venue has a unique niche or cultural mission. For example, if your theater is dedicated to avant-garde performance art or your club is a launchpad for local indie bands, remaining independent ensures those priorities won’t be overridden by profit motives. You can continue to take artistic risks – hosting that experimental jazz residency or a weekly up-and-coming songwriter night – simply because you believe in it. Many historic venues were built on such risk-taking and curation, and by soldiering on independently, they protect that legacy.

Veteran venue managers will tell you that authenticity is an asset in the live music market. Audiences crave genuine experiences, and independent venues often deliver a vibe and character that corporate venues can’t replicate. By staying independent, you can preserve all the little details that make your venue authentic. Think of the dive-bar-turned-venue that still has stickers on the fridge and a jukebox in the corner, or the family-run dance hall that’s been handing the mic to local legends for generations. These features might not be “brand-compliant” in a chain, but at an indie venue, they’re part of the charm. Creative freedom extends to branding and style – you can redesign the space on a whim, paint a mural, host a themed night that’s totally offbeat, all without asking a board of directors. This freedom to innovate can actually be a competitive advantage. Some of the most beloved venues in the world succeeded by being different: they leaned into creative quirks and originality. As long as you’re independent, you maintain the ability to experiment and set trends, rather than follow corporate playbooks.

Importantly, independence allows you to define success on your own terms. Maybe you prioritize cultural impact over maximum profit – running an all-ages community talent show that barely breaks even, because it’s the right thing for your scene. A corporate owner likely wouldn’t allow that, but as an indie, you can balance money with mission. You answer only to your own principles (and, of course, your need to pay the bills – which is its own discipline). Many operators find great personal fulfillment in this freedom: they can sleep at night knowing every decision stays true to their vision. In the long run, venues known for strong curatorial voices often build a brand loyalty that money can’t buy. Fans appreciate when an independent venue sticks to its ethos – it creates a trust that whatever’s on stage was chosen with love, not just dollars in mind.

Authenticity, Community and Brand Loyalty

Independent venues frequently become more than just places to see shows – they’re community institutions. By soldiering on without corporate oversight, you can keep that community-centric spirit alive. Locals often rally around their indie venue, especially if it’s endangered. We saw this during the pandemic: fans bought merch, donated to fundraisers, and lobbied for Save Our Stages to ensure their favorite club survived, transforming from talent buyer to activist overnight and making an essential pivot to survival. When you remain independent, you maintain the goodwill that comes from being a true community player. You’re the venue that sponsors the neighborhood cleanup, or lets the high school hold its battle of the bands on your stage. These tight-knit relationships are hard to foster once a big corporation is in charge, as things get more transactional. Independence lets you continue operating with a people over profits mentality (within reason) that engenders deep loyalty.

This loyalty translates to branding power. Fans often treat independent venues as part of their identity – they wear your T-shirts, plaster your logo on their laptop, tell friends “I basically live at XYZ Club.” That kind of organic brand advocacy tends to diminish under corporate ownership; you rarely hear someone brag about their loyalty to a chain venue in the same way. Staying indie means you can market your venue’s story and soul unabashedly. Your communications can be authentic and local, not sanitized by a corporate PR filter. Many independent venues successfully leverage this in marketing – they highlight being “family-owned since 1985” or “fiercely independent” as a selling point. In a crowded stage of concert options, a strong unique identity cuts through the noise. Real-world case studies show how powerful this can be: Los Angeles’ lodge-like Troubadour (~500 capacity) thrives even in a city dominated by Live Nation theaters, precisely because its intimate, storied atmosphere is one-of-a-kind. Likewise, Tokyo’s tiny jazz kissaten (listening cafés) survive by offering hyper-specialized experiences that no arena or corporate club can match.

An independent venue can also adapt culturally in ways a corporate venue might not. You can reflect your community’s values and tastes fluidly. If there’s a growing Latin music scene in your town, you can pivot to feature those artists; if your city’s underground drag performers need a stage, you can open your doors. There’s no chain mandate to worry about – it’s your call. This cultural responsiveness often reinforces community support: people see the venue as truly theirs, a mirror of the local scene. Over time, that supports not just loyalty but advocacy. Fans will speak up on your behalf to city council or online forums if you’re in trouble, because they feel invested in an authentic venue. As one artist noted, “these venues and the relationships you build through decades… are the life blood of artists” (www.wcbe.org) – independents often champion new artists and local flavor, creating an ecosystem that the music community fiercely protects.

From a branding perspective, independence allows you to avoid practices that anger fans. For instance, many indie venues pride themselves on transparent, fair ticketing (no surprise fees, no surge pricing), whereas corporate ticketing is notorious for add-on fees and dynamic pricing that frustrate concertgoers. By choosing a ticketing platform that aligns with your fan-friendly values – perhaps a service that doesn’t implement surge pricing and gives you full customer data control – you can turn this into a competitive advantage. (Many independent venues have switched to more flexible ticketing systems in recent years to differentiate from Ticketmaster-dominated corporates. Platforms like Ticket Fairy, for example, boast features like no dynamic pricing, white-label branding, and anti-scalping resale, which indies leverage to build trust with fans.) This is an example of how staying independent lets you put fans first without pressure to squeeze every dollar. Over time, treating fans right because you can further cements your venue’s positive reputation and word-of-mouth buzz.

Agility and Innovation on Your Terms

Independence means agility. Independent venues can react and innovate quickly – an invaluable trait in the ever-changing entertainment industry. Without a corporate chain of command, if you as the owner see an opportunity or a problem, you can respond immediately. For instance, if an emerging genre is suddenly hot in your city, you could launch a weekly showcase next month to capitalize on it. If patrons are complaining about slow bar service, you can personally jump in, retrain staff or even revamp the menu by the next weekend. This speed and flexibility are difficult for corporate venues, which may need extensive approvals for changes. Being nimble helped many independents survive recent challenges: during the pandemic, indie venues rapidly pivoted to live streams, DIY outdoor shows, or drive-in concerts, while corporate venues often stayed dark waiting for top-down directives. In 2026, trends like AR-enhanced shows or last-minute pop-up events are easier to implement as a small independent outfit than within a large bureaucracy, helping you punch above your weight.

Innovation thrives in independent venues because new ideas don’t get bogged down in red tape. Your team can try experimental approaches to audience engagement (maybe a gamified scavenger hunt in the venue), test out novel ticketing models (like a pay-what-you-can night or subscription memberships), or collaborate with local artists on space makeovers – all without needing a corporate green light. If something fails, you learn and move on, without headlines in trade magazines or a boss in HQ second-guessing you. This freedom to fail and iterate is the hallmark of many great venue operators. It’s how they discover what really resonates with their crowd. Over time, some indie venues even set industry trends this way, which bigger players later adopt. For example, the modern resurgence of phone-free concerts (locking away phones for a more immersive experience) started with independent venues and comedians trying it out, well before any major arena considered it, as noted in discussions about weighing a festival buyout.

Agility also shows in how independents handle challenges. If an equipment issue threatens a show, indie crews often get creative – borrowing gear from a nearby bar or asking a regular to volunteer for a night – solutions a corporate rulebook might not allow. Noise complaint from neighbors? The owner can visit them personally the next morning with apologies and free tickets, a human touch that resolves conflict faster than any legal department letterhead. Local decision-making lets you navigate regulatory hurdles or community issues with nuance. You can negotiate directly with local authorities for exceptions or permits; many independent venue owners sit on community boards or have personal relations with city officials, which helps them innovate in programming (like starting an all-ages matinee series) that might require special approval. Rather than one-size-fits-all corporate policies, you tailor solutions to your unique context.

In business terms, this agility can equal a leaner operation and higher efficiency. You’re not paying corporate overhead or franchise fees; profits can be reinvested directly into your venue or staff. If you identify a money-waster, you cut it. If a great freelance marketing guru shows up, you hire them tomorrow. Independence encourages a continuous improvement mindset driven by passion, not bureaucracy. Over years, nimble independents often build a loyal patron base precisely because they keep things fresh. The layout might change, the offerings evolve, but it’s always in response to what the community wants – something corporate venues struggle to do with the same authenticity and speed.

Financial Upside and Legacy Value

While it’s true that independence means bearing all financial risk, it also means keeping all the rewards if things go well. Independent owners often have lower profit margins, but they enjoy 100% of those margins. If you hit on a successful formula – a weekly event that sells out, a viral social media moment that boosts ticket sales, or simply a streak of great bookings – the increased revenue can be plowed back into the venue or taken as profit without having to pay a corporate master. Over years, a well-run independent venue can accumulate significant value. Many such venues own their real estate or have long-term favorable leases, and as the neighborhood grows, so does the asset. By not selling out, you maintain the equity upside. If your five-year plan grows the venue’s business by 50%, that value belongs to you (and any partners you chose to bring in on your terms) – not to an external shareholder.

Some owners are motivated by the idea of building a family legacy or an employee-owned legacy. Staying independent keeps alive the possibility that you could pass the venue on to your children, your management team, or even sell it later to a local cooperative or foundation that will honor your original mission. We’re seeing innovative models like community ownership emerge: In the UK, the Music Venue Trust’s Own Our Venues initiative is buying venue properties to lease back to operators affordably, ensuring they remain independent community assets. A venue that doesn’t sell to a corporation might instead sell shares to fans or artists. For instance, a beloved venue could raise money by letting 500 fans invest a small stake each (something that has happened via crowdfunding in multiple countries). This way, the venue stays independent but gains capital and literally community ownership. Those paths disappear once a corporation is in the picture.

There’s also a pride in ownership that many independent venue operators value more than a big payday. Being the boss and knowing you built something from scratch – it’s hard to put a dollar value on that. Some owners just aren’t happy unless they’re steering the ship. They’d rather navigate occasional storms than hand over the helm. For those folks, the day-to-day enjoyment of running a venue their way outweighs the appeal of cashing out. They find creative ways to solve financial challenges while staying true to themselves, whether through side businesses (like starting a record label or bar spin-off) or seeking out aligned investors who don’t demand control. A great example is an independent theatre that wanted to renovate but not sell; they found a mission-aligned private investor willing to put in money for a minority stake with zero interference in artistic decisions – essentially patient capital that kept the venue indie. Deals like this are possible when you commit to independence and get creative.

Finally, consider legacy and long-term potential. Today’s small independent could become tomorrow’s iconic venue that defines a city’s music scene – but only if it stays independent and nurtures that identity. Think of venues like First Avenue in Minneapolis, or Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Colorado (city-owned but independently operated essence) – their legendary status comes from decades of unique operation, not being replicas of a formula. If you believe your venue has the ingredients to be one of those special places, you may decide to soldier on and chase that legacy, rather than cash out early. The financial upside, in that case, might come later in different forms: perhaps your brand becomes so strong you open a second venue, or you write a book, or you eventually negotiate a sale from a position of much greater strength and value. Independence keeps those options open.

Challenges of Going It Alone: Why Independence Is Hard

Financial Strain and Capital Constraints

For all its rewards, running an independent venue is undeniably risky and costly. The financial strain is the number one challenge operators cite. You’re on the hook for every expense – and venues have many. Rent or mortgage, utilities (imagine heating or cooling a large hall), insurance, staff wages, equipment upkeep, licensing fees – the bills are relentless. With slim margins, one unexpected hit can be devastating. A roof leak, a major sound system failure, a sudden lull in ticket sales, or an economic downturn can drain your reserves quickly. Unlike a corporate-owned venue, you can’t call headquarters for emergency funds. Access to capital is limited to what you can scrape together via bank loans, personal savings, or perhaps local investors. Many indie venues operate month-to-month, especially coming out of the pandemic era. In fact, a 2025 industry survey showed nearly two-thirds of independent venues in the U.S. were in a financially unstable position – essentially living on the edge. That chronic stress can wear down even the most passionate owner.

Major improvements or expansions can be prohibitively expensive without a partner. Say you dream of adding a balcony to increase capacity by 200 seats, or you need $250,000 to overhaul an aging electrical system. As an independent, securing that money means taking on debt (if you qualify for a loan) or finding investors willing to bet on you. Banks often view music venues as high-risk, so loans may come with high interest or require personal assets as collateral. Some venue owners turn to creative financing – revenue-sharing deals, selling a small equity stake, crowdfunding, or pre-selling VIP memberships – to gather funds, as detailed in guides on financing your venue’s future. These approaches can work (and many are covered in guides to engaging your community for funds), but they demand significant effort and savvy. It’s not as simple as a corporate parent writing a check. The harsh reality is that some needed upgrades just don’t happen; independent venues often operate with outdated equipment or décor because the money isn’t there. This can slowly erode the customer experience and the venue’s competitiveness over time.

Independents also bear all the downside risk. If an event loses money, you eat the loss. If there’s a freak snowstorm and two big shows get canceled, you refund tickets and still pay staff and artists per contracts – a double whammy on your finances. Insurance can offset some catastrophes, but not all (pandemic losses taught us that). This means indie owners must be meticulous about budgeting and cash reserves, far more than a corporate venue manager who knows the parent company can bail them out. Essentially, you need to be prepared for Murphy’s Law. Many owners hold back a portion of bar revenue or maintain a line of credit for emergencies. But seeing that contingency fund dwindle is nerve-wracking. The stress is real: independent owners privately admit to sleepless nights worried about making payroll or covering the next utility bill in slow months. The financial strain has forced plenty of great venues to close or consider selling. It’s often said that venues aren’t a way to get rich – and as an indie, you must be prepared that even breaking even some years is a victory, especially when starting out.

Limited Resources and Staffing

Running a venue independently can feel like a juggling act where you never have quite enough hands. Limited resources affect every department. As an indie, you probably have a small full-time staff and rely on part-timers or volunteers for many roles. There’s rarely a budget for specialized positions like a full-time social media manager or an in-house sound engineer on salary (many indie venues have freelancers per event). This lean staffing means people wear multiple hats. The booker might also handle marketing; the venue owner might find themselves unclogging toilets or doing the nightly cash count because there’s no one else. During busy times, this can lead to burnout and mistakes – simply because the operation is stretched thin.

Training is another challenge. Large venue firms have structured training programs and knowledge sharing; independent venues often learn by trial and error. New staff might shadow for a night, then they’re thrown into the deep end at a sold-out show. If your security team could benefit from de-escalation training or your sound techs from advanced audio workshops, as an indie you have to either find affordable external training or hope they self-teach. It’s hard to invest in staff development when margins are tight, which can lead to higher turnover. Keeping talented staff can be tricky when competitors (including corporate venues) might offer better pay or benefits. Many indie venues foster a family-like culture and mission loyalty to retain staff (people work there because they love it, not for the money), but even the most dedicated employee has limits if they’re underpaid and overworked.

Equipment and infrastructure are also often limited. You might have just enough gear to get by, without backups. If the only spotlight breaks, that’s it for lighting until you can afford a fix. Corporate venues often have redundancies (backup amps, extra cables, secondary generators); independents may be scrambling to borrow from a friendly bar down the street when something goes down. This lean approach requires ingenuity – and indeed, indie crews are famously resourceful – but it also means the margin for error is slim. Technical glitches or maintenance issues can more easily derail a show when resources are scant. And when a venue does invest in a big upgrade, it’s a huge decision with risk: you hope the new sound system or air conditioning will draw enough extra business to pay for itself, but you can’t be sure until after the spend.

Administratively, independent venues might lack the sophisticated tools that larger operations use. Maybe you’re using a basic spreadsheet for scheduling and a free ticketing app that doesn’t give robust analytics. This can lead to inefficiencies – double-bookings, lack of customer data, or missed sponsorship opportunities simply because you don’t have the bandwidth to chase them. Modern event tech offers some affordable solutions (many indies are now adopting all-in-one event management platforms that integrate ticketing, marketing, analytics to save time), but choosing and learning new tech itself requires time – which is in short supply for a small team. It’s a vicious cycle: you need more resources to operate efficiently, but you need to operate efficiently to free up resources.

All of this means independent owners and managers work long hours. It’s not uncommon to find the owner doing a full office day of emails and planning, then jumping behind the bar or in the sound booth at night when the show is on. Burnout is a real danger. If an owner or key manager gets exhausted or sick, there may be no backup to seamlessly take over their duties. Many independents avoid taking real vacations for fear the venue might literally not function in their absence. This lifestyle cost is something to weigh: corporate backing often promises a better work-life balance (since more staff can cover roles), whereas staying independent might mean years of relentless hustle. Passion and community love can fuel you a long way, but personal health and relationships can suffer if the venue consumes every waking moment. This is often a hidden con of independence that owners must manage proactively (by building the best team they can, delegating where possible, and learning to say no to things that overstretch their capacity).

Competitive Disadvantages

Independents face an uphill battle competing with the big players. Economies of scale allow corporate venues to sometimes undercut prices or offer deals an indie can’t match. For example, a large promoter might offer artists better guarantees or more marketing support if they play the promoter’s owned venue instead of an indie competitor. If Live Nation or AEG owns multiple venues in your region, they might do block booking – telling an artist’s agent “we’ll book you in Venue A, B, and C (all ours) and promote the tour heavily, but skip that indie Venue D.” This kind of clout can siphon away acts that you’ve cultivated. An independent in a small market often finds it has to prove itself extra hard to agents who default to the known reliability of the big companies. The strategies to attract major artists as an independent include building personal relationships, being flexible in deals, and emphasizing your unique audience connection. It can be done – indie venues in small markets do land big acts by focusing on artist hospitality and niche appeal – but it’s a grind. You might pay higher fees or accept lower profit on some shows to compete.

Marketing reach is another disadvantage. Corporate venues benefit from national advertising campaigns, large email lists, and cross-promotion on ticketing platforms. As an indie, you rely on your local marketing hustle. You’re essentially one venue vs a multi-venue machine. If a corporate venue down the road is pushing a show, it might appear on Ticketmaster’s homepage, get radio ads as part of a bundle buy, and social media posts from a central team. Your show might live or die by your in-house marketer’s ability and a modest ad budget. This makes it harder to sell out events consistently, especially for mid-level acts that rely on marketing to drive awareness. Indie venues counter this by developing grassroots marketing tactics – street teams, local media partnerships, loyalty programs, and engaging storytelling about their shows. Modern tools like social media leveling the field somewhat, but algorithms can be fickle. It takes constant creativity (and often personal connection with your audience) to market effectively on a shoestring. If you slip, the corporate competitor might sweep up those ticket buyers.

Access to talent is not just about booking, but also tech and services. Corporate venues can attract top sound engineers, lighting designers, and security personnel because they might offer slightly higher pay or more stable work across their network. An independent might struggle to keep the best crew or end up as a stepping stone where people gain experience then leave for bigger venues or tours. Additionally, buying power differences mean corporate venues can afford better equipment, as mentioned, which can itself attract artists (bands know which venues have the great new PA system or a high-end monitor rig – they may prefer those for a better show experience). Some indie venues level the playing field by renting extra gear for high-profile shows or forging partnerships (e.g., a local music shop sponsors them with equipment), but it’s a continuous effort.

Even on the customer side, competition is tough. Corporate venues might offer perks like exclusive credit-card pre-sales, VIP clubs, or bigger-name opening acts that draw crowds. An independent has to excel in experience to keep loyal fans choosing them. If your bathrooms are older and space is tighter, you have to compensate with amazing sound, intimate atmosphere, friendlier staff, and the sense of community that corporate venues may lack. Often, service is the battlefield – indie venues strive to give artists and fans a personal, memorable experience that the somewhat cookie-cutter big venues can’t. But doing so on a limited budget (e.g., you can’t afford to comp as many drinks or invest in fancy décor) is a challenge. As more new state-of-the-art venues open (many corporate-funded), older indies especially feel the pressure to justify why fans should come to a possibly less-comfortable space. Keeping up with venue technology and trends (from cashless payments to immersive visuals) requires careful investment when independent. There’s a risk of falling behind and being seen as outdated.

None of these challenges are insurmountable – countless independent venues do compete successfully, often by focusing on what big venues can’t do: offering unique content, fostering local scenes, and providing a human touch. They also sometimes band together; independent venue coalitions can share booking leads or do cross-promo to collectively counter a giant, as suggested by strategies like collaboration over isolation. But an honest appraisal must acknowledge that independence often means swimming upstream in a business sense. You’ll have to be smarter and more tenacious to achieve the same results a corporate-backed venue might get with a fat budget. For those up to the challenge, this is a point of pride – the classic underdog story. Yet it’s also a grind that can wear down even the most ardent operators if not prepared for it.

Personal Stress and Burnout

Operating an independent venue isn’t just a business challenge; it’s an immense personal journey – one that can take a toll. We need to talk about burnout. The live events world is fast-paced and high-pressure by nature (show days are long, late nights are routine), and when you’re independent, the buck stops with you 24/7. Owners often internalize every setback: a low turnout or a negative review isn’t just a blip, it feels like a personal failure. Over time, this pressure cooker environment can lead to fatigue, stress-related health issues, or simply losing the joy that once motivated you.

Many indie venue operators have stories of near breaking points. For example, when a headliner cancels 48 hours before a sold-out show, it’s the independent owner who scrambles to find a replacement or manage refunds – and eats the financial loss – while dealing with furious fans and disappointed staff. A corporate venue manager, in that scenario, would have a whole support apparatus and likely insurance to handle it; the indie owner has only grit and maybe a bit of goodwill stored up. After a few such crises, even the toughest can feel burned out. It’s common to wear multiple hats daily (as we noted, booking in the morning, fixing fixtures in the afternoon, greeting bands at soundcheck, supervising the door at showtime, then doing accounting after hours). Work-life balance can be almost nonexistent. Family and relationships may suffer; hobbies fall by the wayside. Essentially, your venue becomes your life. This level of dedication is admirable and often necessary for success – but it’s not sustainable indefinitely for most people.

Stress can also come from the loneliness of command. Independent owners don’t have a corporate hierarchy to escalate problems to. Tough decision about firing an underperforming longtime staffer? Heart-wrenching call on whether to shut down a beloved weekly event that’s losing money? It’s all on your shoulders. During the pandemic, many venue owners had to pivot to activism and fundraising to save their businesses, transforming from talent buyer to activist and making an essential pivot to survival, taking a huge emotional toll as they fought for survival. As one operator said, “I try not to think about [selling]… it’s a chilling thought,” but the stress of potentially losing it all is ever-present, a fear shared by many financially vulnerable independent music venues. Even in good times, there’s the stress of staying ahead – the independent must constantly adapt and hustle to keep the venture afloat, with no guarantee of payoff. It’s easy to neglect self-care and mental health under these conditions, which ironically can hurt the business (burned-out owners make poorer decisions and lose the charismatic leadership that is often key to a venue’s vibe).

All this isn’t to say corporate GMs don’t experience stress – they certainly do – but the nature of the stress is different. An independent’s stress is deeply personal and existential (my life savings and dream are on the line every day), whereas a corporate venue manager, while under pressure, ultimately has the company’s backing and it’s “just a job” in the sense that they could step away without the whole venue collapsing. Recognizing this difference is crucial when weighing the paths. Some people thrive on the independent lifestyle; they have the stamina, support system, and passion to fuel them through the toughest stretches. Others recognize that they might burn out and that their venue might actually do better with more support. There’s no shame in either. One healthy approach many indie owners take is to build a strong team and delegate as much as possible – essentially, create your own internal support network. This can alleviate personal stress (for example, grooming a reliable general manager or talent buyer so the owner isn’t the single point of failure). But finding and affording such help loops back to the challenges above.

In summary, the human factor is a big consideration. If you remain independent, plan for how you’ll keep yourself and your core team motivated, healthy, and sane. The advantage is you’re fueling a dream on your own terms; the challenge is that dream can consume you. Many independent venue veterans emphasize the importance of setting boundaries and sustainable practices (like scheduling dark days to rest, saying no to events that strain resources, and seeking mentorship from fellow indie owners to share coping strategies). By confronting the risk of burnout honestly, you can better prepare to soldier on for the long haul without losing your love for the game.

Real-World Venue Journeys: Lessons from Both Sides

Thriving After a Corporate Acquisition

It’s helpful to look at venues that took the leap into corporate ownership and flourished – these success stories illustrate what’s possible with the right partner. One example is Irving Plaza in New York City. This historic 1,200-cap club was independently operated for years before Live Nation took over its lease. Rather than ruin the venue’s legacy, Live Nation invested heavily: a top-to-bottom renovation in 2019-2021 preserved the venue’s 19th-century charm but vastly improved amenities and sightlines and added upscale VIP lounges. Post-renovation, Irving Plaza reopened with a packed calendar of diverse acts (over 40 shows in the first month) and has remained a staple of the NYC concert scene. Fans returned in droves, lured by the venue’s upgraded experience combined with its original character. This shows that a corporate owner can pour resources into a venue to ensure it remains competitive in a major market. The key was Live Nation respected what made Irving Plaza iconic while layering improvements (and of course, having the capital to do so). The outcome has been positive financially and reputationally – the venue holds its own against newer venues, and artists rave about the improved production and backstage comfort.

Another case is international: Impact Arena in Bangkok, a 12,000-seat venue that partnered with Live Nation in 2025. Impact Arena was already a premier venue in Thailand, but the corporate partnership aimed to modernize it for a new era. Live Nation’s involvement is bringing state-of-the-art upgrades – from enhanced F&B and premium seating to backstage tech that allows faster changeovers. They’re also leveraging their global talent network to route more world-class tours through Bangkok, positioning Impact Arena as a must-play venue in Asia. Early signs indicate this will boost the local concert economy and fan satisfaction. Crucially, Live Nation emphasized working with the local landowner and keeping local culture in mind, as noted by Live Nation Asia’s leadership, suggesting a collaborative approach. If successful, Impact Arena will illustrate how a corporate operator can elevate a venue to international standards, benefiting both fans (through better shows and amenities) and the local scene (through more opportunities and economic impact). It’s essentially a win-win: the venue stays at the heart of the community’s live music, now with global backing.

Even smaller venues have found benefits in corporate deals. Consider a mid-size UK venue like the O2 Academy Liverpool (formerly the Lomax decades ago). Under independent operation, it had its ups and downs. Once absorbed into the Academy Music Group (with O2/Live Nation sponsorship), it got much-needed refurbishments and a consistent pipeline of UK tour acts, thanks to being part of the Academy brand. Attendance improved and the venue remains a cornerstone of Liverpool’s music circuit. Fans initially skeptical of the O2 branding eventually appreciated that the venue was hosting more shows than it might have otherwise. Similarly, some family-run venues in the U.S. that partnered with regional promoters report being able to expand their programming – like adding comedy nights and podcast tours – because the promoter provided expertise and connections beyond the owners’ own network.

Of course, not every sale is smooth sailing, but these examples highlight a pattern: the most successful corporate takeovers preserve what’s unique about the venue while injecting capital and professional muscle where needed. Owners who choose the right partner – one that values the venue’s legacy – can see their venue thrive and even grow beyond what was possible solo. One festival-oriented example: Goldenvoice (creator of Coachella) was acquired by AEG, and Coachella famously grew into a global trendsetting festival under that partnership, improving infrastructure and grounds. Translating that to venues, a similar dynamic can occur: the right corporate partner might take a good venue and make it a great one, in a sustainable way.

The lesson from success stories is that if you do opt to “sell out,” due diligence on who you sell to is everything. The best outcomes happen when the corporate entity truly understands the venue’s brand and audience, and the original owners perhaps stay involved to guide continuity. Negotiating terms that protect some of your venue’s identity (like agreeing on booking autonomy for certain nights or keeping key staff) can set the stage for a smoother transition. When done right, selling can mean seeing your venue renovated, your financial burdens lifted, and your calendar busier than ever – a satisfying legacy knowing the venue will live on and flourish.

Flourishing as a Stubborn Independent

Equally important are the stories of venues that stayed independent and succeeded against the odds. One shining example referenced earlier is The Troubadour in West Hollywood. This legendary ~500-capacity club opened in 1957 and remained independent through wave after wave of industry consolidation. Even as Live Nation and others bought up many L.A. venues, the Troubadour thrived by focusing on its historic strengths: an intimate atmosphere and reputation as a launchpad for iconic artists. By leaning into its identity (the walls are covered with decades of music history, and the vibe is famously up-close-and-personal), the Troubadour continued to sell out shows and attract major surprise gigs by artists who cherish its significance. Fans and artists alike see it as hallowed ground – a corporate chain venue simply can’t manufacture that kind of authenticity. In 2020, when COVID threatened its existence, the community, big-name musicians, and fans rallied to raise funds to save it, precisely because it’s an independent institution. It emerged from the pandemic still under its own ownership, and by 2026 it’s as vital as ever, hosting both rising stars and secret shows by legends. The Troubadour’s story shows that independence can be a powerful brand and that by carving out a unique niche, a small venue can hold its own even in a city full of corporate competitors, much like Tokyo’s tiny jazz kissaten or by carving out your venue’s niche.

Another inspiring case is London’s 100 Club. This basement venue (cap ~350) has been operating since 1942, famed for its role in jazz, punk, and Britpop history. By the 2010s, it was struggling financially (facing high rents on Oxford Street), but instead of selling to a chain, it doubled down on its legacy. The 100 Club received support from fans, the local council, and even a sponsorship from Converse at one point – innovative partnerships that kept it independent and embraced the authenticity. They leveraged their storied past (photos and memorabilia of historic gigs adorn the club) as a draw, differentiating themselves from newer, sterile venues. Now, the 100 Club remains a bucket-list venue for many artists precisely because it’s an authentic, independent space where so much music history lives. Its operators have been able to modernize just enough (improving sound and ventilation, for example) through grants and sponsorships, without handing over control. They also continually adapt their programming to nurture new scenes (hosting everything from indie rock to Northern Soul dance nights), ensuring they stay relevant to younger crowds while keeping longtime patrons happy. The result: a thriving venue that’s both living museum and cutting-edge incubator, immune to the homogenization that comes with corporate branding, making the venue unlike any other.

We also see examples of independent venues finding strength in numbers, not via a corporation but via alliances. In some countries, venue collectives share resources to remain independent. For instance, a group of indie venues might form a booking collaborative so they can tour artists among themselves, bypassing the big promoters. Or they unify marketing under an “Independent Venues of [City]” banner to jointly attract sponsors and media attention. By staying indie but working together, these venues achieve scale without selling. A real-world case: in the Netherlands, several small venues formed a network to coordinate programming and collectively pitch for government funding – each venue stayed autonomous, but they acted as one when needed. This helped them survive competition and avoid being picked off individually.

Some venues have even come back to independence after being under corporate management! A case in point is the Mesquite Rodeo Arena in Texas: it was managed by a corporate firm for a while, but the local ownership took it back to focus more on community events and diversification beyond just rodeos, which the corporate approach had limited. Since regaining independence, they expanded into concerts and motocross, tailoring offerings to local tastes better and improving profitability. It’s a reminder that corporate management is not always superior – local operators with freedom can sometimes perform better by being more in tune with their market.

The overarching lesson from successful indies is know your unique value and exploit it. Independents that flourish usually have a clear identity or market position and double down on it. They also adapt creatively: if money is short, they find new revenue (hosting a weekly vinyl market or renting the space for film shoots on off days). If competition is tough, they zig when others zag (booking genres the big venues ignore, or providing a more personal fan experience). They deeply engage their community – turning customers into evangelists. And critically, they run a tight ship financially, even if informally. Many share the philosophy, “We can’t compete on cash, so we compete on passion, authenticity, and agility.” When executed well, that can absolutely succeed in 2026’s market. Fans will go where they feel a connection and where they sense the love of music is genuine – and independent venues often have that in spades.

Cautionary Tales and Course Corrections

Not every story is rosy. There are venues that sold to a corporate entity and regretted it, as well as independents that nearly went under before making changes. These cautionary tales provide valuable insights. One example of the former: a mid-sized U.S. venue (which we’ll keep unnamed) sold to a national chain in the late 2010s. The new owners rebranded it, raised ticket fees, and started booking more generic cover bands instead of the eclectic mix it was known for. Regulars abandoned the venue, and the local music press lamented the loss of a cultural gem. Within a few years, attendance dropped so much that the corporate parent divested it. The venue ended up closed, and only after some time did independent promoters bring it back to life under a new name. The moral: a buyout can fail if the new operator doesn’t respect the audience and identity that made the venue successful. Fans can tell when a venue’s priorities shift purely to profit. In this case, the corporate approach actually made the business worse, not better, proving that bigger isn’t always better if misaligned.

On the independent side, many venues have come to the brink of closure and learned hard lessons. A common theme is financial mismanagement or lack of adaptation. An owner might keep doing things “the way we always did” while the market moves on – leading to declining sales and mounting debt. Pride or denial can prevent seeking help until it’s almost too late. For instance, some older indie venues resisted updating their booking strategy or investing in marketing, thinking their legacy alone would carry them. When attendance dwindled, a few tried to hold out by cutting costs (sometimes cutting the very things that made them good). Only when faced with the real possibility of selling or closing did they make bold moves like launching crowdfunding campaigns, applying for grants, or bringing in new partners. Those that survived often credit swift action and community engagement at the eleventh hour. One venue in Seattle realized they needed new revenue and swiftly implemented smarter inventory management and upselling strategies – boosting their bar profits enough to stay afloat. Another in Melbourne started hosting off-night events like trivia and viewing parties which, though not concerts, helped pay the bills and keep staff employed until the concert business picked up again.

A particularly poignant case was Tipitina’s in New Orleans – a legendary independent club founded in 1977. By 2018, the longtime owners were in financial trouble and almost had to sell to outside investors. Instead, a group of local musicians (the band Galactic) stepped in to purchase Tipitina’s, keeping it independent but under new stewardship. They invested their own money to pay off debts and took over operations in 2019. It was a risky move born of love – they didn’t want to see Tipitina’s fall into possibly non-local hands or change in spirit. Fast forward to 2020: the pandemic hit, and even these new owners struggled. They publicly shared that many parties had approached them trying to buy the club as a “distressed asset”, a situation where venues could resort to another sale. They refused, but admitted it was scary, and they needed federal aid and community support to survive, making an essential pivot to keep going. They also pondered what venues look like if help doesn’t come. Thankfully, they got through it, and Tipitina’s remains a vibrant, musician-owned independent venue to this day. The cautionary element is clear: even a rescue by passionate insiders can be tested by external crises. The continued independence of such a venue relies on adaptability and sometimes external support (e.g., government grants, fan fundraisers) – things an owner should be ready to pursue if they choose to remain independent through hard times.

These cautionary tales highlight a crucial point: whether independent or corporate, staying true to what makes a venue special is paramount. Corporations that ignore a venue’s “soul” can squander their investment. Independents that neglect sound business practices or fail to evolve can destroy their dream. The good news is, course corrections are possible. We’ve seen corporates adjust tactics after backlash (some have reinstated local managers’ autonomy or toned down fee increases when faced with fan revolts). We’ve seen independents bring in new partners or professionalize certain aspects (like outsourcing their ticketing to a more efficient platform or hiring a business manager) rather than lose everything. The decision to sell or not isn’t irreversible either – some owners have bought back venues or spun off new independent projects after an unsatisfying corporate stint, applying lessons learned.

In the end, every venue’s journey is unique, but all can learn from each other. When making your decision, be mindful of these stories: the successes, the failures, and the rebounds. They prove that no outcome is guaranteed by choosing one path or the other – execution and alignment matter most. Next, we’ll break down practical considerations to help you figure out which path aligns with your goals, and how to navigate whichever choice you make.

Deciding What’s Best for Your Venue: Key Considerations

Clarify Your Vision and Goals

The first step in this decision is a bit of soul-searching: what do you really want for your venue? Revisit why you started (or bought) the venue in the first place. Was it for the love of music and community? To build a family business or a cultural landmark? Or was it primarily an investment you hoped to scale and profit from? Your core mission and long-term aspirations should guide your choice. If your venue’s identity is tightly bound to independence and a unique ethos, partnering with a corporation could undermine the very thing you set out to create. On the other hand, if your goal has always been to grow the venue into a larger enterprise or franchise, then teaming up with an industry giant might align with that vision.

Consider writing down your top priorities. For example: “Provide a home for underground artists,” “Be the top-grossing venue in my market,” “Expand to multiple locations,” “Preserve this historic theater for the community.” Rank them. If keeping creative control and cultural authenticity outrank financial growth for you, that leans towards staying independent (or finding a very mission-aligned minor investor at most). If scaling up and securing the venue’s financial future is at the top, a corporate partnership may be a logical avenue. Be brutally honest: sometimes owners realize their personal goal is to retire comfortably in a few years – selling could facilitate that, whereas staying independent might not. Others realize they’d rather close the venue than see it change in ways they disagree with – those owners often double down on independence and seek other solutions.

It’s also useful to envision your venue’s ideal future. What does it look like in 5 or 10 years? Is it still the intimate space where locals gather, or do you see it evolving into a larger, more commercial venue? Are you still at the helm, or do you want to step back and let others run it eventually? If you love the day-to-day of running shows and curating experiences, staying independent keeps you in the driver’s seat creatively. If you’re tired and looking for an exit or retirement plan, selling might be attractive – perhaps you can hand over the keys, so to speak, and see the venue continue (hopefully thriving) without you, while you reap some financial reward for your decades of work. This ties into personal life goals as well: there’s no shame in deciding you’ve achieved what you wanted and it’s time to move on – just ensure the deal you make honors your venue’s legacy if that matters to you.

One more angle: think about your emotional reaction to each scenario. Does the thought of your venue under a corporate banner make you relieved, sad, excited, indifferent? Does the thought of staying independent make you feel proud, anxious, energized? Your gut feeling is not the only factor, but it’s important. Some owners simply could not bear to see their “baby” in someone else’s hands; that tells you independence might be worth fighting for despite the challenges. Others secretly feel a tinge of excitement at the idea of being part of a bigger enterprise (imagine seeing your venue’s name added to a roster of legendary halls, or having access to industry events and resources through a corporate network). That suggests openness to selling if the terms are right. Clarifying your vision and feelings upfront will help anchor you when you weigh the practical pros and cons.

Assess Your Venue’s Financial and Market Situation

Next, take a hard look at the numbers and the competitive landscape. Can your venue survive and thrive financially on its own? Open up your books (or better yet, get an accountant or advisor to help if you’re not comfortable) and project the next few years. Consider best and worst case scenarios. If you’re barely breaking even or operating at a loss with no clear path to improvement, independence will be tough to sustain unless you find new revenue or cut costs. Have you explored all options to boost revenue? This could include event sponsorships and brand partnerships (many indies offset costs with a couple of strategic sponsors), diversifying programming (e.g., hosting comedy nights or private events on off days), or improving margins via better operations like inventory control at the bar. If you find that even with these strategies your venue’s cash flow is insufficient for necessary investments (new equipment, building repairs, hiring staff), that leans towards needing outside help – which could mean a sale, or perhaps taking on investors/loans while remaining indie.