In the high-stakes world of live events, how a venue structures its booking deals can mean the difference between a profitable night and a financial fiasco. Deal or no deal? In 2026’s live music landscape, that question looms larger than ever. Skyrocketing artist fees and razor-thin margins have venue operators carefully weighing guarantees versus splits, rentals versus co-promotes. This comprehensive guide demystifies the major booking contract structures – from flat guarantees and “versus” deals to revenue-sharing splits and full venue rentals – and shows how to pick the right deal for each show. Drawing on decades of global venue management experience (and plenty of hard lessons learned), we’ll explore how smart deal negotiation and clear settlement practices protect a venue’s bottom line. Real-world examples from clubs, theaters, and arenas around the world illustrate what works and what to watch out for. By the end, you’ll have actionable advice to structure fair agreements with artists and promoters, avoid common financial pitfalls, and ensure every post-show settlement is smooth, transparent, and sets you up for long-term success.

The 2026 Booking Landscape: High Stakes & Hard Choices

Post-Pandemic Boom Meets Cost Pressures

The mid-2020s have brought a paradox for venue operators. On one hand, live event demand is rebounding strongly – global concert grosses hit record highs by 2024, and fans are willing to pay more than ever for great experiences (the average top-tour ticket passed $130 in 2024). On the other hand, the costs to put on those shows have surged. Artists who lost touring income during the pandemic now often demand higher guarantees, and production expenses (from staging to security) have climbed with inflation. Veteran venue managers note that headline talent fees have jumped 30–40% since 2020. This means every show carries more financial risk if not structured wisely. A single bad deal can wipe out profits from several good nights.

Venues also face tougher competition for content. Major promoters and festivals are aggressively bidding for artists’ limited touring dates, sometimes pricing out independent venues. Intense “talent wars” in 2026 put pressure on venues to offer attractive terms to land shows – but overbidding can be perilous. As a result, many venues are rethinking how they allocate risk in booking contracts. It’s no surprise that external promoter partnerships are on the rise; teaming up with outside promoters to share risk and fill dark nights has become a go-to move for many venues. In short, the stakes are high, and deal structure is now a critical strategic decision.

Why Smart Deals Matter More Than Ever

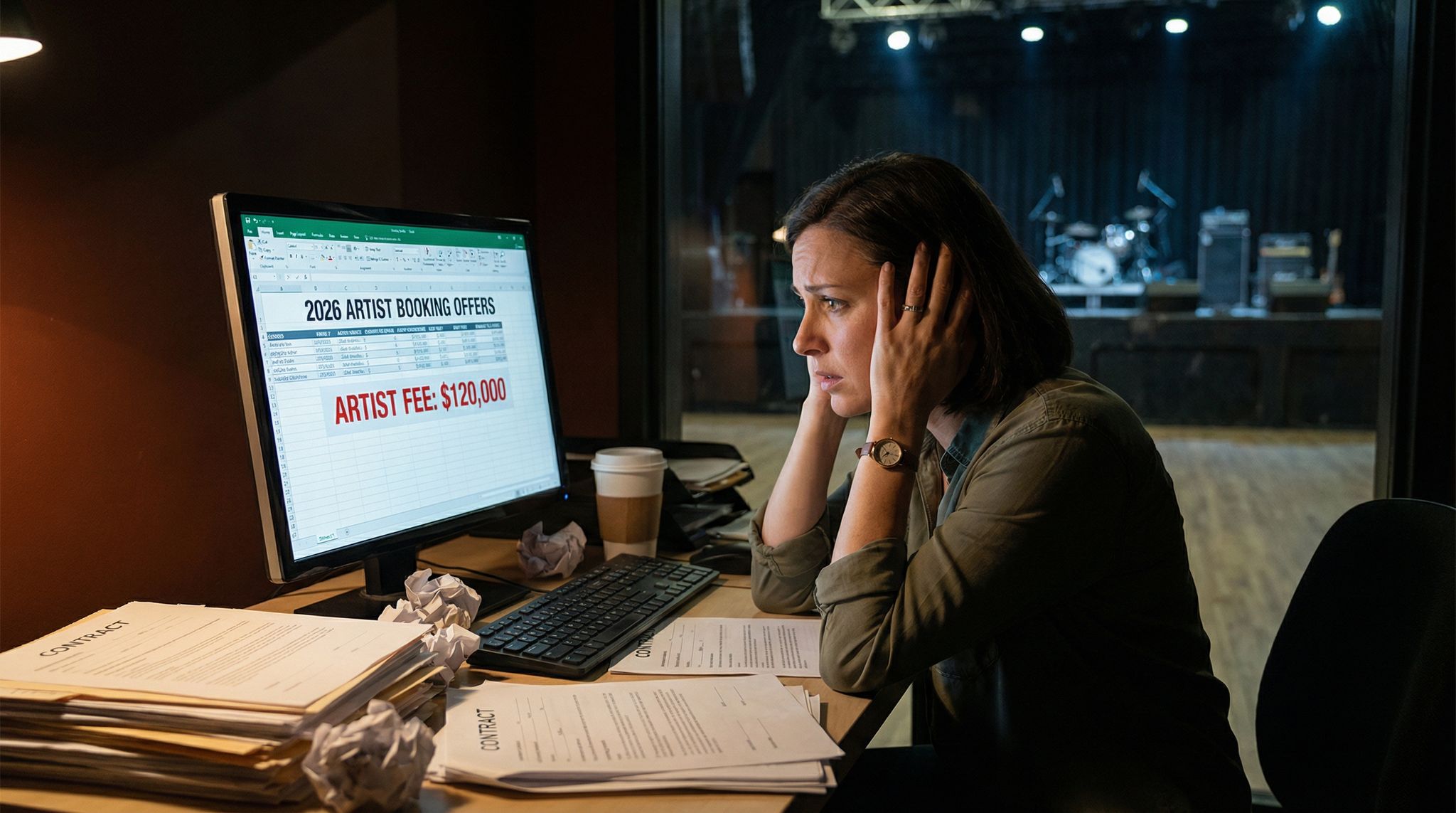

When margins are slim, the deal you cut can make or break your year. A 2025 industry report in the UK found 53% of grassroots music venues failed to make a profit that year, despite contributing over half a billion pounds to the economy. With such tight margins, venues simply cannot afford to consistently overpay artists or misjudge an event’s draw. Each booking contract must be evaluated not just on the excitement of the artist, but on hard financial realities. For example, if a mid-sized venue pays a superstar DJ a $100,000 flat guarantee but only sells $80,000 in tickets, that’s a $20k loss before even counting operating costs – a hit many venues can’t absorb.

Boost Revenue With Smart Upsells

Sell merchandise, VIP upgrades, parking passes, and add-ons during checkout and via post-purchase emails. Increase average order value by up to 220%.

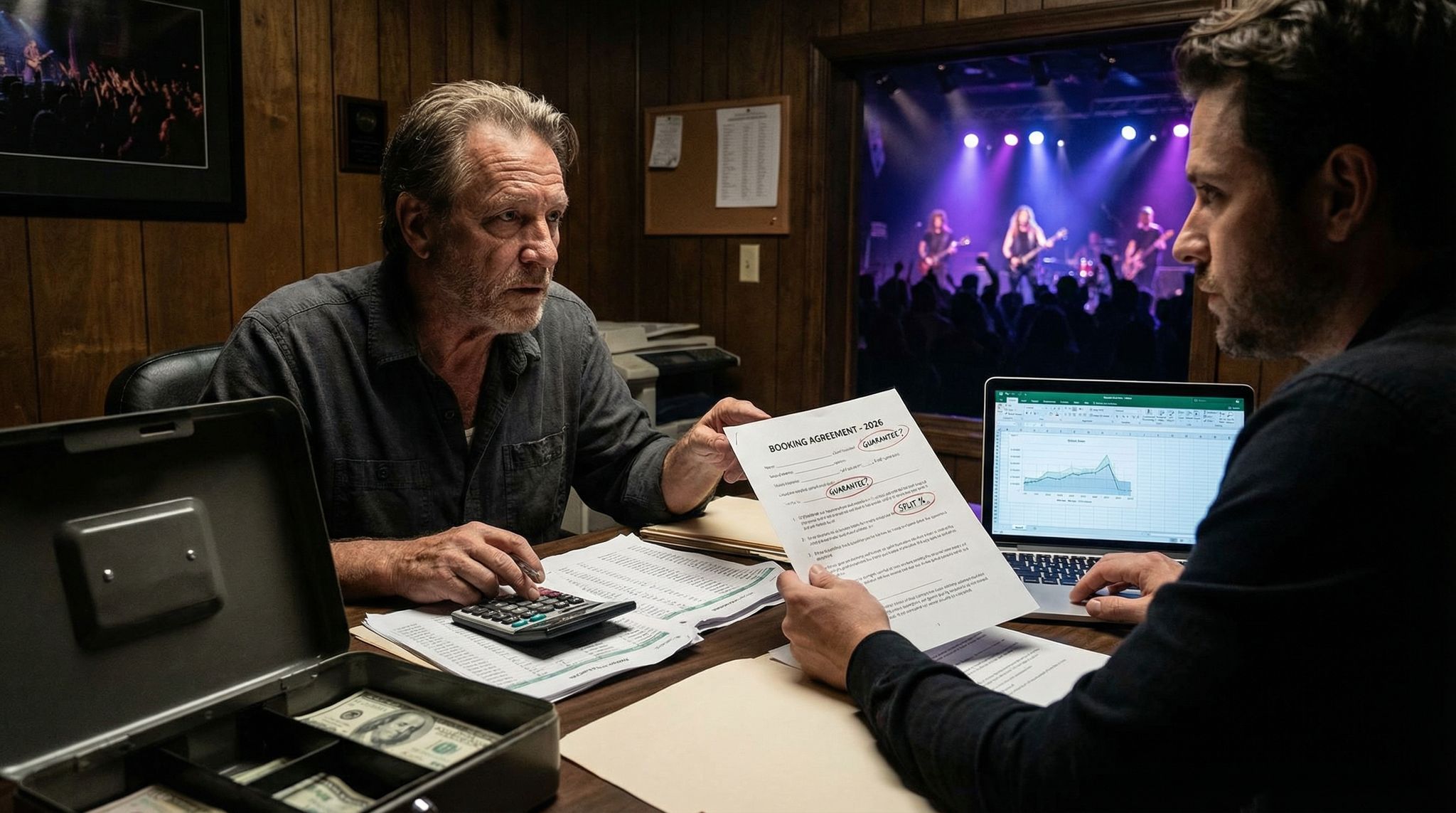

Experienced venue operators have learned to plan every deal with a calculator in hand. Before agreeing to terms, they project best-case, expected, and worst-case ticket sales for that event. (In fact, many use data-driven booking budgets to forecast revenue and break-evens to run the numbers before agreeing to terms.) By matching the deal structure to the level of uncertainty, you can protect the venue on risky shows and still capitalize on surefire hits. As we’ll explore, deals can be engineered to share risk with artists or promoters so that everyone has skin in the game. The goal is to avoid the nightmare scenario of an empty room with a big guarantee due – and instead create scenarios where both the venue and the artist win when a show succeeds.

Finally, getting the deal right isn’t just about one night’s balance sheet – it’s about your venue’s reputation and relationships. Agencies and promoters talk, and venues known for fair, transparent deals often get repeat business and better bookings. On the flip side, a venue that gains a reputation for squeezing artists unfairly (or defaulting on payments) might find tours skipping them. In 2026’s interconnected industry, trust and goodwill are currency. Structure your contracts to protect your business and treat your partners well, and you’ll build a sustainable calendar instead of chasing one-off wins.

Ready to Sell Tickets?

Create professional event pages with built-in payment processing, marketing tools, and real-time analytics.

Breaking Down Common Deal Structures

Flat Guarantees (Straight Fees)

A guarantee is the simplest deal: the venue (or promoter) agrees to pay the artist a fixed fee, regardless of how many tickets sell. For the artist, it’s the most secure arrangement – they know exactly what they’ll earn. For the venue, however, a flat guarantee is the highest risk. If the show flops, the venue still owes the full amount. Guarantees are standard for major artists who can command big fees. For example, if a popular act asks for a £50,000 guarantee to play a 2,000-capacity theatre, the venue must be confident they can gross at least £50k in ticket sales (after taxes and fees) or accept the loss.

The upside of a guarantee is straightforwardness and potential profit if the show sells beyond expectations. Once the artist’s fee is covered, the venue keeps all remaining ticket revenue. In a best-case scenario – say the show sells out instantly at high ticket prices – the venue can make a healthy profit because the payout to the artist doesn’t increase. That lottery-ticket upside is why some venues accept guarantees for superstar acts. For instance, a theatre might pay a flat $100,000 to land a one-night show by a legendary band, betting it will sell out and maybe even allow a second night. As long as sales are strong, a flat fee can work fine (especially when combined with robust merchandise, bar, and VIP sales that the venue keeps).

However, flat guarantees should be handled with extreme care. For most mid-level acts or newer artists, paying a big guarantee is like walking a tightrope without a net. Seasoned venue managers recommend setting a guarantee only at a level you’re very confident the show will meet or exceed in gross ticket sales. Some even insure or cap their downside by negotiating a lower guarantee plus a backend (more on that next), rather than a bloated flat fee. In practice, flat guarantees are best reserved for must-book artists on dates you know will draw – think Friday or Saturday shows with proven hitmakers. For anything less certain, it’s wise to explore a deal structure that shares the risk.

Revenue Splits (Door Deals)

A revenue split, often called a “door deal,” means the artist’s pay will be a percentage of ticket sales. No tickets sold, no pay – and if it sells out, the artist’s pay grows with the revenue. These deals typically specify a split after certain basic expenses (sometimes called the house nut) are covered. For example, a common arrangement in club venues is an 80/20 split of the net door: the artist gets 80% of ticket revenues after agreed expenses/taxes, and the venue keeps 20%. Other splits might be 70/30, 85/15, or any ratio that the parties agree on.

Turn Fans Into Your Marketing Team

Ticket Fairy's built-in referral rewards system incentivizes attendees to share your event, delivering 15-25% sales boosts and 30x ROI vs paid ads.

The beauty of a door split is that it inherently balances risk. If only 50 people show up when 500 were expected, the artist’s payout shrinks accordingly, softening the venue’s loss. Conversely, if the show is a smash hit, the artist shares in the upside (and the venue still earns its percentage). This alignment can create a collaborative feel – both venue and artist are motivated to promote the show to maximize attendance. Grassroots venues and developing artists often prefer splits for this reason: it’s fair and scaleable. For instance, an indie band just starting to draw a crowd might gladly take 70% of whatever comes through the door instead of a small guaranteed fee. If 100 tickets at $20 are sold, and the venue’s $300 in costs are covered, the band gets 70% of the remaining gross – about $490 in total earnings – whereas a flat $300 guarantee might have left money on the table for them. If only 20 people show up, the band might earn very little, but the venue isn’t stuck paying hundreds out-of-pocket either.

For venues, revenue splits are low risk financially – you’re never paying more than the event actually brought in (aside from sunk production costs, which ideally were covered off the top). Many independent clubs survive by doing mostly door deals with local and emerging acts. It lets them host lots of shows without the cash flow crunch of big guarantees. However, splits do mean the artist is taking on more risk – not every artist will accept that, especially if they have significant travel costs or a set paycheck in mind. Some artists also worry that door deals could incentivize a dishonest promoter to under-report ticket sales. The solution there is transparency: provide a clear audit of ticket counts and use a reputable ticketing system. Modern venues often leverage tech (like scanning and real-time sales dashboards) to ensure every ticket is accounted for at settlement – building trust that a 80/20 split is truly 80/20.

Grow Your Events

Leverage referral marketing, social sharing incentives, and audience insights to sell more tickets.

In 2026, door deals remain common for club shows, support acts, and any situation where both sides are gambling on turnout. They work less well for superstar tours (big artists usually won’t accept “maybe” money when they can demand guarantees elsewhere). But even at higher levels, hybrids like versus deals incorporate the spirit of a door split, ensuring an artist isn’t “stuck” with a low payout if the show blows past expectations. Ultimately, revenue-sharing deals are a vital tool to keep booking new talent sustainable for venues. They turn potential losses into break-even nights and give artists a chance at earning more by driving ticket sales.

Versus Deals (Guarantee vs. Percentage)

The versus deal is a popular hybrid that combines a guaranteed minimum with a revenue-based upside. In a versus structure, the artist is promised a base fee (guarantee) or a percentage of ticket sales – whichever is higher. This is often written as “$X vs. Y% of gross (or net).” For example, an offer could be “$1,000 vs. 70% of net box office receipts (NBOR)”. What does that mean? If 70% of the ticket revenue after expenses comes out to less than $1,000, the artist still gets $1,000. If 70% of the net sales comes out to more than $1,000 – say $1,500 – then the artist gets the higher amount ($1,500). In other words, the guarantee is their safety net, and the split is their bonus for a packed house.

Versus deals aim to strike a balance between artist and venue interests. The artist has the comfort of a minimum payday, while the venue’s risk is lower than with a straight guarantee – because if ticket sales are weak, at least you might not owe beyond the guarantee. It effectively caps the venue’s downside a bit, compared to an oversized flat fee. At the same time, if the show is a hit, the artist isn’t limited to a small guarantee; they share in the wealth, which can make them happy and more eager to play your venue again. Many business-savvy artists and agents appreciate versus deals for mid-tier markets or uncertain plays: they know they’ll be taken care of if the crowd is smaller than hoped, but also that they won’t “undersell” themselves if the show does gangbusters.

From the venue perspective, a versus deal is medium risk and medium reward. You do have to pay that guarantee no matter what, so a flop still hurts – but usually the guarantee in a versus deal is set lower than a would-be flat guarantee for the same artist. (For instance, an artist might accept $5,000 vs 80% instead of a non-negotiable flat $8,000 fee, because they see a chance to earn more on the backend.) If the gig only sells 50%, you might lose some money, but not as much as if you’d guaranteed $8k. If it sells out, yes, you’ll pay the artist more than the minimum, but presumably you also made more thanks to high ticket revenue – so you’re sharing profits, not digging a deeper hole.

One important element in versus deals is defining the breakpoint or split point – essentially the level of sales at which the percentage kicks in beyond the guarantee. Often it’s simply when net income exceeds the guarantee amount. Promoters sometimes talk about “going into backend” or “going into overage” – this means the ticket sales have hit the point where the artist’s share goes beyond the base guarantee. At settlement, any overage is calculated and paid out according to the agreed split. It’s critical that all expenses to be deducted (if any) are clearly defined upfront. Many versus deals are based on a percentage of net revenue (after certain expenses like venue rental, sound, marketing, or taxes). Being crystal clear on what “net” includes is vital; otherwise, disputes can arise if the artist expects 70% after only hard costs, but the promoter tries to include every little expense. Good contracts list exactly which costs come off the top and which don’t. The industry standard is to list a reasonable set of costs (approved by the artist/team beforehand) – for example: credit card fees, PRS/ASCAP fees, and basic venue operating costs might be allowed, but not, say, the promoter’s first-class flight to the show!

In summary, versus deals are a versatile tool in 2026. They are commonly used for mid-level artists, busy touring acts in secondary markets, or any scenario where an artist has decent drawing power but there’s still some uncertainty. Many festival offers to mid-tier acts are structured as a cachet vs. a percentage of ticket sales, ensuring fair upside. When crafted well, a versus deal builds goodwill: the artist feels taken care of and valued, and the venue enjoys a level of protection if things don’t pan out. It’s a classic win-win structure – but it only works if you do the math and negotiate percentages and guarantees that make sense for your capacity and expected ticket price.

Promoter Profit Deals (Splitting the “Nut”)

For larger concerts and tours, especially in North America, you’ll sometimes encounter promoter profit deals (also called split-point deals). This structure is a bit more complex, essentially ensuring the promoter gets a predetermined profit margin before sharing additional revenue with the artist. In a typical promoter profit deal, the contract might say something like: “Artist receives a $50,000 guarantee plus 85% of remaining net revenue after expenses and a 15% promoter profit on those expenses.” In practice, this means the settlement includes an extra built-in cost line item – the promoter’s profit (often 10–15% of eligible expenses) – which is added to the expenses before splitting the pie. Only after the sales revenue exceeds the sum of all expenses plus the promoter profit does the additional 85/15 (artist/promoter) split of overage kick in, as explained in guides to promoter profit deals. (See detailed calculation examples here).

Why use such a convoluted formula? Essentially, promoter profit deals guarantee the promoter (or venue) a baseline profit percentage if the show just meets expectations, before the artist starts taking the lion’s share of extra revenue. It’s a way for a promoter to say to an artist, “I’ll give you 85% of any huge success, but first I need to make 15% on my costs, even in a modest outcome.” For example, if a show’s expenses (venue rent, advertising, production) are $100,000, a 15% promoter profit adds $15,000 to that budget. The split point (breakeven for split) would then be Expenses ($100k) + Promoter Profit ($15k) + Guarantee. Let’s say the guarantee is $50k, then the artist doesn’t start getting 85% of overage until ticket sales have topped $165,000 in that scenario. If the show sells $200,000, then there’s $35,000 of overage to split (85% artist = $29,750 extra to artist, 15% promoter = $5,250 extra beyond their built-in profit). The artist’s total would be $50k + $29.75k = ~$79.8k, promoter’s total profit in the end would be effectively the $15k (built-in) + $5.25k = $20.25k.

As you can see, promoter profit deals get pretty technical, and they’re generally reserved for high-dollar shows where both sides have leverage and accountants on hand. Big agencies may insist on them to ensure their artist isn’t giving up too much potential earnings, while big promoters use them to protect a minimum profit margin. For a venue operator, you’d mostly see this if you’re co-promoting a large concert or working directly as the promoter on an arena-level show. The key is to model it out with real numbers and make sure you’re comfortable with the break-even point. Promoter profit deals can actually be quite fair – they motivate the promoter to control costs (since padding expenses would increase the split point they need to reach anyway) and they ensure the artist isn’t going to walk away with 85% of the gross until the promoter has earned their keep. Just be sure to communicate all these details clearly in the offer and settlement, so nobody is confused on show night about what “15% promoter profit” meant. Transparency, as always, keeps tensions from flaring when calculators come out after the encore.

Full Venue Rentals (Four-Wall Deals)

Not all events are promoted by the venue or a concert promoter – sometimes the easiest deal is simply renting out your venue for a flat fee. In a four-wall rental, the client (an external promoter, event organizer, or even an artist’s team) pays the venue a set rental price to use the space, typically covering a basic agreed package of venue services. In return, the renter gets to keep all or most of the event’s ticket revenue. In essence, the venue acts only as a landlord and service provider, not as a risk-taking promoter. For example, an arena might rent itself for $20,000 + expenses to a promoter bringing a touring show. Or a nightclub might do a four-wall deal for a corporate product launch party at a fixed $5,000 fee, with additional staffing costs billed separately.

For venues, rentals can be low-risk, guaranteed income. Whether the event is full or half-empty, the venue still gets paid the same fee. This makes rentals attractive for filling dates that might be hard to curate yourself – off-night concerts, private events, or niche genres where you’re unsure of demand. Many venues use rentals to cover their base operating costs on weeknights, essentially outsourcing the risk to someone else while keeping the bar revenue and perhaps charging for add-on services (like in-house sound and lighting, security, cleaning fees, etc.). For instance, a historic theater might rent to a local promoter for a one-off boutique festival; the promoter handles booking and marketing, while the theater collects rent and feeds the audience with concessions.

However, rentals come with trade-offs. The obvious downside is that the venue forfeits any upside from a wildly successful show. If the promoter sells out the event and rakes in profit, the venue doesn’t share in that windfall beyond maybe some ancillary income (parking, concessions). Another consideration is wear and tear: a flat rental fee needs to be priced high enough to cover not just basic costs but also the intangible “impact” of the event. If you rent out a 5,000-cap arena for a heavy metal festival and the place gets thrashed, you’d hope the fee accounted for the intensive cleanup and any repairs. Many venues structure rentals with tiered pricing or extra charges if an event exceeds normal usage (e.g. an extra security fee for a particularly rowdy concert). If set up correctly, though, a four-wall deal shifts financial risk firmly to the renter. Some inexperienced promoters have learned this the hard way – they pay the rent, then struggle to sell enough tickets and end up deep in the red. From the venue’s perspective, that’s regrettable (you want your partners to succeed so they come back), but at least your balance sheet is protected.

In 2026, full rentals are increasingly common in certain segments of the industry. Corporate events, influencer-hosted parties, esports tournaments, and community festivals often operate on a rental model – essentially venue-as-venue, not as co-promoter. Even major concert promoters like Live Nation will sometimes do flat rental deals for smaller markets or secondary tours, accepting all the risk so the venue just provides the space. If your venue is municipally owned or tied to a public institution, you might even be required to offer rentals (some city-owned venues must make themselves available for community use at set rates). The key is to price rentals smartly. Research what similar venues charge and consider your cost structure: you want a fee that makes it worth it to “go dark” on your own promotion and host someone else’s event. Many venues also negotiate hybrid rentals – for example, a slightly lower flat rent plus a small percentage of ticket sales, so the venue has a little upside if the show does well. This can be a compromise if a promoter can’t afford your full rate upfront. Flexibility in deal structures – being open to creative twists like that – can help you attract more outside events to fill your calendar while still protecting your bottom line.

Comparing Deal Types at a Glance

It’s helpful to see all these deal structures side by side. Here’s a quick reference comparing how each one works and the risk/reward for the venue versus the artist or promoter:

| Deal Structure | How It Works | Venue’s Risk & Reward | Artist/Promoter’s Risk & Reward |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flat Guarantee | Pay artist a fixed fee regardless of ticket sales. | High risk – Venue shoulders all financial risk; needs strong sales to profit. If sales are weak, venue loses money. Upside: if sales are great, venue keeps all excess revenue after paying flat fee. | No risk – Artist is paid full amount even if tickets lag. Limited upside: artist’s earnings don’t increase if the show sells out (unless bonuses included). |

| Door Split (Revenue) | Split ticket revenue by percentage (after costs). | Low risk – Payout to artist flexes with sales; venue isn’t stuck with huge loss on a bad night. Upside: venue still earns its share (20–30%, etc.) on any tickets sold, and event costs are usually covered first. | Higher risk – Artist’s pay is not guaranteed; a small crowd means low income. High upside: if show packs out, artist earns more than they might have with a flat fee, proportional to sales. |

| Versus Deal | Guarantee vs percentage, whichever is greater. | Medium risk – Venue owes at least the guarantee, even if sales are weak, but guarantee is typically moderate. Some upside share if sales are strong (depending on the deal split). | Medium risk – Artist has a safety net (minimum guarantee) so not playing for peanuts, but a slow night might mean they only get that minimum. Good upside: artist benefits from a big night by getting the higher percentage amount. |

| Promoter Profit Split | Guarantee + profit margin built into expenses; remaining profits split (e.g. 85/15). | Medium risk – Similar to versus: venue/promoter guarantees base fee and covers costs but secures a built-in profit % before splitting additional revenue. Controlled upside: venue gets a predefined cut of profit plus a small share (e.g. 15%) of any extra, but most upside still goes to artist. | Lower risk – Artist has guarantee and only goes into split after promoter achieves agreed profit. High upside: once past breakeven + promoter profit, artist usually takes the majority (e.g. 85%) of remaining revenue, yielding very high potential earnings on a sellout. |

| Full Venue Rental | External party rents venue for flat fee; keeps tickets. | Very low risk – Venue’s income is guaranteed (rent fee). No concern about ticket sales. Downside: no share in ticket windfall if event is hugely successful; must ensure rent covers all costs. | High risk – Promoter/organizer pays rent no matter what. They bear all risk of ticket revenue shortfall, but high reward if event does extremely well (after covering venue rent and other costs, all remaining profit is theirs). |

Table: Summary of common booking deal structures, how revenue is divided, and the risk distribution for venue vs. artist/promoter.

Every deal type has its place. The art of venue booking in 2026 is knowing when to use which structure. Often, it’s about finding the sweet spot between guaranteeing an artist enough to confirm the show, and not over-extending the venue if things go south. In the next section, we’ll discuss exactly how to choose the right deal for each situation – because context is everything.

Choosing the Right Deal for the Right Event

Matching Deal Structures to Event Types

No single deal model works for all occasions. Savvy venue managers adapt the contract structure to the specifics of each event – considering the act, the expected audience, the day of week, and more. Small club gigs vs. arena concerts illustrate the polar extremes: a 200-capacity club hosting an unknown indie band might default to a door-split or modest guarantee, whereas a 20,000-seat arena landing a top artist will involve large guarantees or co-promoter deals. In between, the shades of gray are where careful judgment is needed.

One key factor is event type and genre. For example, music festivals and soft-ticket events (where the audience isn’t buying a ticket just for one artist) often pay artists flat fees – the draw is the whole lineup or experience, so percentage deals make less sense. A jazz festival might guarantee each performer a set fee funded by sponsor dollars and weekend pass sales. On the other hand, club nights or DJ parties with door sales might lean toward revenue splits, especially if it’s an up-and-coming DJ whose draw is unproven. If you’re hosting a corporate event or private function, a rental or buyout is usually the way to go: the client pays you for the venue and handles entertainment themselves, or you book entertainment within a set budget they provide. And as noted earlier, mid-week shows or off-peak nights often call for creative deals – perhaps a lower guarantee plus a % of the door – since attendance is harder to predict than the prime Friday/Saturday slots.

Think also about genre expectations. Some genres have industry norms: for instance, many hip-hop and electronic artists work on flat guarantees (plus maybe bonuses) because that culture expects a set fee. In contrast, punk rock and indie scenes historically embraced door deals (think of the classic “$5 at the door, bands get 70%” arrangement at DIY venues). These norms aren’t absolute, but understanding them can guide your negotiation. If the artist’s agent is accustomed to one model, pitching a different structure may require careful explanation of benefits. It’s all about matching the deal to the event dynamics and what will attract the talent and work for your finances.

Assessing Artist Draw and Fan Base

The artist’s popularity – or uncertainty thereof – is arguably the biggest factor in structuring a fair deal. How many tickets can they realistically sell? If the act is a proven draw in your market, you might be comfortable offering a solid guarantee to secure the date. For instance, if a comedian has sold out your 1,000-seat theatre twice in the past, offering a flat fee for a one-night return might be low risk (you have historical sales data to back it up). By contrast, if an artist is untested in your city – maybe it’s their first headline show in a new market – a versus deal or hard split could be wiser to hedge against an overestimate.

When assessing draw, data is your friend. Look at the artist’s past ticket sales in comparable markets or venues. Poll their streaming numbers, social media engagement, and even local buzz. If you’re unsure whether they’ll draw 100 or 1,000 people, that uncertainty should push you toward a deal that shares risk. As a rule of thumb, experienced promoters often say: Guarantees are for when you’re 90%+ confident in the turnout; splits/versus are for the 50/50 cases or total unknowns. In 2026, there’s also the wildcard of last-minute sales – fans often buy late, reflecting that demand is high but purchase windows are shrinking. So an artist might have low advance sales but a big walk-up crowd. If you gave a huge guarantee and the walk-ups never materialize, you’re in trouble. But if you had a split, you simply pay out less.

Also consider artist fanbase factors. Is the artist popular with a demographic that tends to show up, or one that’s flaky? Are they riding a new viral hit that might pack the place, or are they past their prime, where demand is unsure? For rising local talent, you might do a split or a small guarantee just to cover their base costs – it builds goodwill and supports turning local acts into true headliners over time. For a legacy artist doing a reunion tour, you might lean on higher guarantees because their older fanbase will reliably buy tickets (and you have pre-sale data, etc., to guide you). The artist’s track record and trajectory should influence how much risk you’re each willing to take. In sum: the more confidence you have in an artist’s draw, the more guarantee-heavy the deal can be; the more uncertainty, the more you should lean to splits or hybrids to protect the venue.

Weighing Risk Tolerance and Reward

Every venue has its own business objectives and risk tolerance. A large corporate-owned arena might be able to take a six-figure loss on a show and shrug it off, whereas a 300-cap independent club could be sunk by one disastrous guarantee. So, know thyself: how much risk can your venue afford? If you’re operating on tight cash flow, prioritize deals that won’t bankrupt you if attendance disappoints. That might mean saying “no” to a big artist’s high guarantee demand and instead booking two smaller sure-fire shows. Or it could mean negotiating a versus deal when an agent asks for something that feels too high. One shrewd strategy some independent venues use is to propose aggregate deals – for example, “I can’t pay you $10k for one night, but I’ll book two nights back-to-back at $6k each vs. a split.” This lowers your risk per night, while giving the artist potential to earn more over two shows (and often the second night’s sales benefit from word-of-mouth from the first). It’s all about structuring terms that align with your financial reality.

Risk tolerance also ties to your broader booking strategy. If a venue needs to maintain a certain profit margin monthly to satisfy investors or keep the lights on, it might avoid speculative deals entirely. Conversely, a venue that’s cultivating cachet might take a loss on a big-name artist occasionally for the prestige or long-term benefits (e.g. attracting sponsors or building the venue’s brand). But even in those cases, the terms matter – maybe you’ll do the big name at a flat fee but negotiate soft points like reduced hospitality or a cap on production expenses to limit the bleed.

Another angle is reward potential: if an event has huge upside (say a breakout artist who could sell out and then some), you might accept more risk in order to secure a piece of that upside. For instance, you might agree to a high guarantee but also insist on a percentage of ticket sales beyond a certain point (essentially a reverse-versus: the artist gets their big guarantee, but if the show sells beyond X, the venue gets a cut of the extra revenue). This is less common but can be a way to compromise with a major act – “We’ll pay your $100k, but if we gross over $150k, we keep 30% of the overage.” Such arrangements are complex (and not every agent will go for it), but it’s an example of tailoring risk/reward. The underlying principle: don’t take on risk without some path to reward. If you’re going to gamble, make sure a win actually benefits you proportionally. If the deal is structured so that you take all the risk and only get a tiny fixed reward even if it goes great – that’s a red flag. It should always feel balanced.

Finally, factor in contingency plans: how will you mitigate risk if an event is under-selling? Do you have the flexibility to adjust ticket pricing, ramp up marketing, or add a support act to boost interest? Venues that excel often pair smart deals with smart promotion. They know that once a contract is signed, the focus shifts to selling tickets. If you accepted a big guarantee, you’d better have a marketing plan to match. In fact, part of choosing the right deal is honestly assessing how much you can do to influence the outcome. If it’s out of your hands (like a rental where the promoter handles marketing), then price that risk accordingly. If you can hustle to boost sales, you might safely take on a bit more risk knowing you’ll work to avoid a flop.

Considering Local Market and Timing

The local market context and timing of a show are additional filters for choosing deal structures. If your city is experiencing a live music boom with frequent sellouts, you might lean more on guarantees – confident that shows will likely fill up. But if the market is saturated or economic factors are suppressing turnout (e.g. layoffs in a one-company town), you may shift to caution and revenue splits. Always ask: what other events are happening around the same date? If three other major concerts or festivals are the same week, even a popular artist might not sell out your venue. In such cases, hedging with a versus or lower guarantee is prudent.

Seasonality plays a role, too. Many venues have busy seasons and slow seasons. An outdoor amphitheater in Canada knows that November is dicey for concerts – so any fall shows might be booked on more favorable terms (maybe co-promotions or shared-risk deals) to entice artists to come despite the weather risk, or simply to protect the venue if chilly temps keep fans at home. A beachfront venue might do guaranteed deals all summer when tourism swells crowds, but opt for door splits in off-season months to avoid losses when the town is quiet.

Day of week is another timing aspect: weekends are prime time, weekdays are harder. If an artist wants a Monday night, a venue operator might say “We’ll do a 70/30 split after costs” whereas that same artist might have gotten a small guarantee on a Saturday. Why? Because even strong acts can struggle on Mondays – it’s just tougher to get fans out, so the venue will want to share the risk. Some promoters explicitly have policies like “no guarantees on weeknights for unproven acts.”

Local regulatory and economic conditions can’t be ignored either. Are there curfews or strict noise ordinances that limit show times (reducing how many tickets you can sell via double-show nights, etc.)? Is there a local entertainment tax or high licensing fees that add costs to each ticket (common in some U.S. cities)? These factors effectively raise the break-even bar for a show and should influence your deal. If you have to pay 5% of gross in city amusement tax, a door split might be better than a guarantee because the tax comes off the top before anyone gets paid – meaning a guarantee deal leaves the venue eating that tax, whereas a split might share that burden implicitly. A smart venue operator in, say, Chicago (which has an amusement tax) will factor that into offers: maybe offering $10k vs 85% of net after tax, rather than $12k flat, so that the artist also feels a bit of the effect of that tax if the show underperforms.

Lastly, consider competitive context: if multiple venues or promoters are vying to book a hot tour date, you might need to sweeten your deal to win it. That could mean upping a guarantee or offering a more favorable split. But be careful – it’s easy to get caught in a bidding war that leaves the winner overpaying. Always circle back to the realistic revenue potential in your venue. Sometimes proposing a creative deal (e.g. a versus with a juicy upside for the artist) can beat a rival’s flat offer because it signals partnership and confidence. Agents often appreciate when a venue says “we’ll share the risk with you.” It can tilt decisions in your favor if an artist values the relationship or the quality of your venue over pure dollars. So use deal structure as a strategic tool: in a tight race for an artist, a well-structured offer that addresses everyone’s needs may triumph over simply throwing more money on the table.

Negotiating Fair & Protective Contracts

Nail Down All Financial Terms in Writing

Once you’ve agreed on the broad deal structure, it’s time to put the details on paper – the contract (or deal memo) is your safety net. A verbal “70/30 split after costs” means little if you haven’t defined which costs, or when settlement happens, or what happens if things change. So, step one: clearly document the deal type, monetary terms, and any formulas in the contract. Specify the guarantee amount (if any), the percentage splits, and exactly how gross and net revenue are defined for your deal. For example, if it’s a versus deal: “Artist shall receive a guarantee of $5,000 versus 80% of Net Box Office Receipts (NBOR), whichever is greater. NBOR is defined as gross ticket receipts less municipal admission tax (5%) and credit card fees (3%).” If it’s a flat rental: “Promoter shall pay Venue a rental fee of $10,000 + VAT, which includes basic venue expenses (list them), with payment due regardless of ticket sales.” As industry experts note, clarity up front prevents conflicts later.

Spell out the payment schedule too. Most deals involve an advance deposit for guaranteed fees – often 50% due upon signing. This protects the artist (and ensures the promoter has skin in the game). List the deposit amount and due date in the contract. Also state when the balance is due (commonly at settlement the night of the show, or within a few days after for wire transfers). If you’re the venue contracting directly with an artist, you’ll typically collect that deposit from yourself (or pay it to the agent) and hold it until show day; if you’re contracting with a promoter renting your venue, you might require them to pay you a deposit on the rent. In any case, get it in writing: “A non-refundable deposit of 50% is due by X date via bank transfer, with the remaining balance payable in cash or certified check on the night of the performance after settlement.” This way, everyone is on the same page about when money changes hands.

It’s equally important to enumerate any other financial promises. Will the artist get a bonus if ticket sales hit a certain number? Put the trigger and amount in the contract (“Artist to receive $1,000 bonus upon 1,000 tickets sold (verified by audit)”). If the deal includes catering buyouts or hospitality stipends, list those (“Venue to provide hot meal or $25 buyout per band member”). Ambiguity is the enemy of trust – and trust is huge in deal-making. Top venue managers follow the mantra: “Assume nothing is ‘understood’ – write it down.” The few extra pages of detail can save a relationship if something goes awry. In the end, a well-crafted contract protects both sides: the artist knows what they’re getting and what they’re not, and the venue knows its obligations and limits of liability. It’s the playbook you’ll refer to when any question arises. If it’s not in the contract, it’s open to dispute – and you never want to be settling a friendly agreement in a courtroom because of a simple omission.

Cover Expenses, Revenue Streams, and Responsibilities

A strong booking contract should clearly allocate who is responsible for each expense and who earns revenue from each source. Don’t assume, for example, that the artist will pay their own travel and the venue will cover marketing – spell it out! Typical expense clauses in venue-booked shows include lists of what the promoter/venue will provide versus what the artist (or external promoter) will cover. For instance, the contract might say: “Venue to provide at its expense: venue staffing (ushers, box office, basic security), house sound & lights, standard marketing inclusion on venue website and email. Artist/Promoter to provide at their expense: backline equipment, specialty lighting, tour catering, hotel and transport.” Tailor this to each deal. If you promised to cover hotel rooms for the band, that goes under your column and ideally with a cap (e.g. “up to 3 rooms for 2 nights at a 3-star property”). If the artist is covering an expense, note it so they can’t later say “we thought you were doing that.”

On the revenue side, clarify each stream. Ticket sales are usually the big one – if it’s a rental, the contract should explicitly state the renter keeps ticket revenue (minus any fees or venue cuts). If it’s a co-promotion, maybe you’re sharing ticket revenue, so detail the split or settlement procedure. Just as critical are ancillaries: merchandise sales, for instance. Does your venue take a percentage of merch sales gross? This has become a hot-button issue in recent years, with many grassroots venues pledging not to take merch cuts, a move supported by organizations like the Music Venue Trust and Association of Independent Promoters as a gesture of goodwill to artists. Regardless of your stance, it must be in the contract. A typical merch clause might read: “Artist retains 100% of merchandise sales revenue. (Venue to provide merch tables at no charge and seller upon request at 0% commission.)” or, if you do take a cut: “Venue commission on merchandise: 20% of gross sales on venue-sold items (excluding recorded media), after local sales tax.” Imagine the fury if an artist expects to keep all their T-shirt money and you spring a 20% cut on them during settlement – that’s how relationships are burned. So be upfront and negotiate it in advance. If you do charge merch fees, justify it (you’re providing staff to sell, etc.), or consider waiving it for smaller acts to build goodwill.

Food & Beverage and alcohol sales are usually all venue revenue, and often not mentioned in artist contracts (since artists rarely get a share of bar sales, except maybe at some DIY punk shows). However, if it’s a private event or co-promote where a client or promoter expects a portion of bar sales (rare, but not unheard of in certain venue rental deals), get that in writing too. Generally, as a venue, you want to keep F&B income – it’s a crucial part of the business model – and most deals reflect that. But always double-check that contracts don’t inadvertently promise something like “Artist receives X% of all event revenue,” which could be misconstrued. It should be specific: ticket revenue, merch, etc., item by item.

Another vital area is production and technical costs. The contract rider often lists what the artist needs (sound, lights, special gear). During deal negotiation, there should be agreement on who pays for any extra equipment rentals or additional crew. If your in-house system is sufficient, great – clarify that it’s included at no extra cost. If the artist is bringing massive LED walls that require a generator, note whether the artist will bear that cost or if you’ve factored it into the deal. Surprises on show day like a $2,000 unexpected generator rental can turn a profitable night into a loss, so allocate those responsibilities early. Some venues use a cost worksheet appended to the contract, essentially the anticipated expense list for the show: e.g. “Venue costs to be charged to show: $500 marketing, $300 hospitality, $1,000 sound techs, etc.” and either those are taken off the top of revenue (if it’s a split deal) or reimbursed by the promoter. The artist or promoter signing the deal should approve those in advance.

Labor and staffing responsibilities should be outlined too. If it’s a rental, often the contract stipulates the renter either must use the venue’s personnel for certain roles (like house electrician, security – often for safety or union reasons) and whether those costs are included or additional. If additional, attach a rate card or estimate. If they can bring in their own people (say, their own sound engineer), clarify if that changes anything in fees or access. Remember, the goal is that come show day, both parties know exactly who is handling every aspect and who’s paying for it. No “I thought you had stage hands for load-out” when it’s 2 a.m. – the contract should have said, for example, “Promoter to provide stagehands, or venue can arrange at $X/hr charge.” Comprehensive? Yes. But that’s the level of detail top venue managers go into, especially as events have gotten more complex.

Protect Against Cancellations and Curveballs

If 2020 taught the industry anything, it’s to expect the unexpected. Cancellations, postponements, and force majeure events (like pandemics, natural disasters, or artist illnesses) are unfortunately part of live events. Your booking contracts in 2026 must have robust clauses to handle these scenarios fairly. Typically, a cancellation clause covers what happens if the artist cancels versus if the venue/promoter cancels. For instance, if the artist cancels the show (not due to force majeure), the contract might stipulate that the artist must return any deposit paid, and neither party owes further damages (or perhaps the artist/agency covers non-refundable expenses incurred up to a certain amount). If you, the promoter or venue, cancel (without cause like force majeure), usually you’d forfeit the deposit to the artist as a kill fee, and possibly cover proven expenses the artist incurred. The exact terms depend on leverage, but make sure it’s addressed. A force majeure clause should excuse both parties from obligation if an act of God or government intervention makes the event impossible, with deposits typically returned or a reschedule attempted.

Post-pandemic, many contracts got even more specific: some now include language about pandemics, epidemics, or even government health restrictions as force majeure events, whereas insurers and attorneys haggle over what triggers refunds. The key is to not leave it vague. Also consider adding a clause about rescheduling: for example, “If an event is postponed due to force majeure, both parties will make a good-faith effort to reschedule. If rescheduled within 6 months, deposits will be retained for the new date; if not, deposit is refundable.” Having a clear roadmap reduces disputes in emotional moments when a show falls through.

Another curveball: underperformance or breaches. It’s wise to include language for if an artist fails to perform a full show (say they storm off stage after 2 songs). Can the promoter pro-rate the fee, or is it still due in full? Some contracts have a “complete performance” clause that the artist must make a good faith effort to perform the agreed set length; if not, remedies can be negotiated (though often, realistically, you’ll settle something privately if that happens). Similarly, if a venue fails to provide agreed equipment or is in breach (maybe the power dies due to negligence), an artist might be entitled to cancel and still receive the guarantee. These situations are rare, but a thorough contract can outline them.

On the more everyday side, include protection about show content and licensing. For example, ensure the artist will not violate any laws or your policies (no hate speech, pyrotechnics without approval, etc.) – this protects your venue’s license and community relations. If they do, you might have the right to shut down the show without full payment, etc. And don’t forget insurance: the contract should require that each party have appropriate insurance. Venues usually carry liability insurance, but you may also require an external promoter to provide a certificate of insurance naming your venue as additional insured for the event. That way, if an audience member is hurt and sues everyone, their insurance will cover promoter-related liabilities.

One more protective element: indemnification clauses (each party agrees to hold the other harmless for certain things) – standard boilerplate but important. And consider a jurisdiction and arbitration clause – if things really go south, specifying how disputes are resolved (e.g. via arbitration, and under which state/country law) can save headaches. These legal points may seem far removed from booking excitement, but they are the guardrails that keep a bad situation from becoming catastrophic. The vast majority of shows won’t need to invoke these clauses, but having them solidly in place is part of being a trustworthy and professional venue operator. Artists and agents notice when you have a well-crafted contract – it signals competence and reliability, which boosts your authoritativeness in their eyes.

Build Trust with Transparency and Fairness

Negotiating a deal isn’t just about numbers – it’s about relationship building. The live entertainment industry is surprisingly small when it comes to reputation. Being fair, transparent, and easy to work with is a form of currency. Many experienced venue managers will recall times when they offered a creative deal to accommodate an artist’s needs, and it paid back tenfold in future bookings or goodwill. For example, if an artist is nervous about taking a door deal, you might negotiate a small guarantee against the door – essentially a versus with a low floor – to show you believe in the show as much as they do. Or you might include a bonus structure: “We’ll do 70/30 split, but if you sell out our 500 cap, we’ll throw in a $500 bonus.” That kind of gesture, written into the deal, shows the artist you’re not out to nickel-and-dime but truly want a win-win. One venue talent buyer shared that he almost always adds something like a hospitality upgrade or small bonus for well-performing shows – it’s not a ton of money, but it leaves acts feeling great about playing your place.

Transparency is crucial from first offer to final settlement. When negotiating, it can help to explain why you’re proposing a certain structure. Instead of just saying “We can only do $500 vs 80%,” a savvy negotiator might add: “Because you’re a new act in our city, our forecast puts the break-even around 150 tickets. We’d rather give you 80% of the upside beyond that than commit to a higher guarantee that could put the show in jeopardy if sales are slow. This way, if you pack it out, you’ll do very well, and if it’s a bit under, we’re not losing our shirt – which means we can invite you back sooner.” That level of candor can set you apart. Many agents and artists appreciate straight shooters. As one veteran promoter says, “Don’t overpromise, over-deliver.” If you are upfront about budgets and then put on a fantastic show that draws a crowd, you’ll gain trust.

Being fair also means avoiding exploitative practices. In the 2020s, there’s a growing awareness around things like predatory ticket deals or “pay-to-play” schemes where artists are forced to pre-sell tickets or pay fees to perform. Respected venue operators steer clear of these. In fact, organizations like the Music Venue Trust and Association of Independent Promoters in the UK have taken stands to reject unfair practices regarding merchandise fees – because they know it’s short-term gain, long-term pain. An artist who feels ripped off will never return and will tell others. So, while as a venue you need to control costs and earn revenue, it pays to examine each policy through a fairness lens. Taking a reasonable cut of merch if you genuinely provide sales staff is one thing; charging a young band 30% of their t-shirt money when you did nothing for it is another. Many venues have dropped merch fees for small shows altogether as a goodwill gesture, and they find that artists sing their praises for it. Similarly, giving local openers a fair deal (maybe a small guarantee or a generous split on their tickets) rather than having them sell tickets for free exposure can foster loyalty. These bands might grow and remember your kindness when they’re filling bigger halls.

In negotiations, listen to the other side’s concerns. If an agent pushes back on a clause, find out why. Maybe an artist had a bad experience where a venue’s “expenses” in a split deal were not capped and ate up all the revenue. You could offer a compromise: a fixed production fee or an expense cap to assure them that won’t happen here. Or if a promoter renting your place balks at the cleaning fee, explain it or adjust if it truly seems high. You’re aiming for a deal where both parties feel it’s reasonable. A grudging partner will lead to friction on show day or after. A satisfied partner will be motivated to put on a great event (which benefits you too).

Finally, always honor your deals. This sounds basic, but it’s worth stating: if you promise something, follow through. There’s nothing worse for trust than a venue trying to back out of a guarantee because ticket sales were bad (“uh, can we pay you less?” – never do this!) or cutting agreed catering to save a few bucks. Likewise, if an artist agreed to a certain split, they shouldn’t try to renegotiate at settlement because the house was packed (“we want 90% now”). Holding the line on the contract, but doing so professionally, ensures everyone knows you mean what you sign. And if you have to enforce a tough term (say, deducting an expense that the artist didn’t expect but is in the contract), do it with transparency and openness – show the receipts, explain calmly, offer a compromise if appropriate. Often, conflicts can be diffused by simply showing that you’re not trying to pull a fast one. “Here’s the invoice for the extra security you requested – as agreed, it comes out of the gross before we split.” When artists and promoters see that you run an above-board operation, they are more likely to work with you again, even if the night wasn’t a home run financially for them. In an industry built on relationships, your word and reputation are everything.

Smooth Settlements: Closing the Night Right

Preparing for Settlement Before Show Day

The best time to ensure a smooth post-show settlement is long before the show even happens. Preparation is key. In the days or weeks leading up to the event, venue accounting staff or the promoter’s rep should have a settlement worksheet or template ready, pre-filled with all known values. This includes the agreed deal terms (guarantee, split percentages, any fixed costs or promoter profit margins) and the budgeted expenses. Essentially, you want a draft profit-and-loss statement for the show ready to go. Many venues use standardized settlement sheets itemizing: Gross ticket sales, minus taxes, minus fees, minus each expense line, etc., ultimately showing the net revenue to be split or paid out. If it’s a rental, it might be simpler (rental fee due, plus any additional charges for damages or overtime if applicable). By prepping this in advance, you can identify any potential issues early. For example, if you see that your advertising spend went over budget by $500, you can alert the promoter or artist’s team before settlement that “Heads up, we invested a bit more in marketing to push last-minute sales – we’ll show that in the expenses.” Surprises kill trust, so aim to eliminate them.

One often overlooked aspect is ensuring you have accurate ticketing data at your fingertips. Ideally, your ticketing system provides real-time reports of tickets sold, gross revenue, comp tickets issued, etc. Before the show, pull a ticket audit report: how many sold in each price tier, how many comps, how many VIP or other categories. Check that against the capacity and holds to make sure numbers align (e.g., if you have 1000 capacity and report shows 950 sold + 50 comps, it implies a full house). If something seems off, investigate before settlement – it’s easier to fix a ticket count discrepancy in the afternoon than at midnight when everyone’s tired. If you use modern tools like QR code or RFID ticket scanning, plan to capture the “drop count” – how many actually attended the event – since some expenses or taxes might be based on that. For instance, PRS in the UK or ASCAP in the US often charge a fee based on attendance or gross, which is part of settlement.

Also, gather invoice copies and receipts for any show-related expenses you need to deduct or share. If the deal says you’re recouping marketing costs, have those invoices (ad buys, flyer printing, social media boosts) printed or in a PDF ready to present. Same for rental equipment, security, catering, etc. A professional settlement binder or digital folder with all backup is extremely impressive to artists’ tour managers – it shows you run a tight ship. Some larger venues have an accountant or dedicated “settler” who will handle this – in smaller venues it might be the GM or promoter themselves wearing that hat. Either way, organization matters.

Finally, touch base with the artist or promoter’s rep on the day of show about settlement timing and needs. Typically, near the end of the night, someone from the venue (often the booker or finance person) and the tour manager or promoter will sit down to settle. Early in the evening, find that person and say hello. Confirm what form of payment they expect – cash or check or transfer – and ensure you have it ready. If you owe the artist money, many will want cash for smaller shows (club tours often settle in cash for convenience and trust), or a wire for larger sums. If you expect to receive money (like a rental balance due), remind them kindly. Confirm where and when to meet (some venues have a “settlement office,” others do it in the production office or even on a corner of the stage after the crowd leaves). Establishing this plan prevents the awkward “Where’s the promoter? We need to get paid” scramble at 1 AM. It’s also a sign of respect and professionalism that greases the wheels for later.

Executing the Settlement: Accuracy and Clarity

When the final encore has ended and the house lights come up, it’s settlement time. Both parties should come together with all the data and make sure the numbers align. Start with the most basic: ticket sales figures. Pull the final ticketing report (the box office or ticketing manager should provide this immediately after the box office closes). It will list total tickets sold, total gross, any fees, taxes, and net amounts. Go through this line by line together, confirming the gross revenue. If the deal is a door split or versus, this number is the cornerstone. If it’s a flat rental, the gross might not matter to the settlement (except perhaps to note if any venue fees like facility fees per ticket are due). But either way, agree on the number of tickets sold and total money collected. If there were any price changes or promo discounts during sales, make sure those are accounted for.

Next, list the expenses being deducted or charged as per the contract. Common ones on settlement sheets include: rental fee (if splitting after a rent), credit card fees, ticketing commission, advertising, PRS/ASCAP royalty, stagehands, sound/light hire, catering, security beyond house provision, hospitality overages, and so on. Each item should have a cost and ideally a backup receipt if significant. For example, “Advertising: $500 (see attached invoices for radio ads).” Usually, you’ll subtotal these and subtract from gross to arrive at a Net to Split (if it’s a split deal) or Overage (if a versus and gross minus costs minus guarantee yields an overage). Go slowly and allow the artist’s tour manager or promoter to ask questions on each item. Transparency is key: if something was comped or the cost is being eaten by the venue, you can mention it (“We actually comped the cost of the extra spotlight operator, so it’s not listed here – just so you’re aware we handled that”). It earns goodwill to show what you didn’t charge as well.

Now, the payout calculation. If it’s a guarantee-only deal, it’s simple: confirm the guarantee was paid (minus deposit if already given) and you’re done – usually just hand them the balance payment. If it’s a split or versus, do the math together. For example: Gross $20,000, minus $2,000 expenses = $18,000 Net. If the deal is 80/20 to the artist after expenses with no guarantee, then artist gets $14,400, venue $3,600. If there was a guarantee, say $10k vs 80%, then you compare the $14.4k to the $10k: clearly $14.4k is higher, so artist gets $14.4k total (if you already advanced $5k deposit, you’d pay $9.4k now). Show the math step by step: “So your 80% comes to $14,400. Subtract the $5,000 deposit we paid your agent – here’s the reference – leaves $9,400 due. We’ll round up the $0.** to make it easy, here’s $9,400 in the envelope along with a settlement statement for your records.” The tour manager counts the cash or verifies the check, both parties sign the settlement sheet (always have a sign-off line for both promoter and artist rep), and voila, it’s official.

One tip: use technology to reduce errors, but always cross-verify manually. Many use Excel or Google Sheets to calculate splits – that’s fine, just double-check key numbers. If you’re computing in front of them, even better – a calculator on the table and both parties checking fosters trust that nothing fishy is happening. There are also specific software and apps for event settlement, some tied to ticketing systems. Those can speed up the process by auto-importing sales data. But even then, giving the other party a chance to review each line is a professional courtesy. This isn’t Wizard of Oz behind a curtain; think of it as both of you reviewing a report together.

A clear settlement not only avoids arguments, it also builds credibility. Artists and promoters talk to each other about venues – if you consistently produce clean, accurate settlements without delay, word spreads that “they’re pros, you won’t have to fight to get paid there.” This is especially important in an era where, sadly, a few venues have tried to cut corners or add mysterious fees. By being the opposite – completely above-board – you differentiate your venue as a class act.

Post-Show Payments and Record-Keeping

After the counts are done and the money is handed over, make sure to tie up any loose ends. For example, if the settlement is done but payment is being sent the next business day (common for larger amounts via wire/ACH), provide a written acknowledgement: “Balance of $X due via bank transfer by Friday, account details on file.” Email a copy of the signed settlement sheet to the agent or promoter as confirmation. There’s nothing like prompt follow-through to show your trustworthiness – if an artist leaves the venue with the promise of a wire, they should receive that wire exactly when stated. Lapses here can damage relationships quickly.

Also, consider if merchandise settlements need to happen (often separately). If you took a percentage of merch or provided sellers, the merch manager and venue rep should count the merch sales and settle that cash as well. Usually, this is done concurrently in another corner – e.g., “We sold $5,000 in merch, at 0% venue cut for soft goods but 10% for CDs, which were $500 of that, so venue gets $50, here you go, sign here.” It might seem small, but every piece of the financial puzzle should be documented and agreed.

Once the artist and promoter are content and heading out, internally the venue team should record the event’s financial outcome in your systems. This means updating your event budget vs actual, filing copies of settlement sheets, and noting any variances (did you spend more on security? Was the payout higher due to a sellout? Etc.). This data is gold for future booking decisions – it feeds back into that data-driven planning. Perhaps incorporate these insights into an after-event debrief to improve operations. This helps you run the numbers for future booking decisions. For example, if the settlement revealed you overspent on production, maybe next time that cost should be on the artist or built into the deal. Or if an artist easily sold out at that split, maybe next time you can confidently offer them a higher guarantee (because you have evidence of demand).

One more thing: say thank you and keep communications positive. After settlement, thank the tour manager or promoter for a good show (even if it was mediocre business, you can thank them for their professionalism or effort). If it was a great night, express enthusiasm to do it again. These personal touches at settlement go a long way. Everyone is tired at the end of a show – a little courtesy and warmth can leave a lasting impression. Some venues even prepare a quick settlement summary sheet to send to the promoter/agent the next day, breaking down the payout with all the figures in a nice format. It’s not required, but it’s a nice documentation that the agent can reference when reconciling on their end, and it underscores that your venue is organized and on top of things.

In essence, a smooth settlement isn’t just an accounting exercise – it’s the final handshake of the event. By making it efficient, transparent, and cordial, you close out the night on a high note, setting the stage for future collaborations and bolstering your venue’s reputation in the industry.

Real-World Lessons: Deals Gone Wrong (and Right)

Lesson 1: The Perils of Over-Guaranteeing

A mid-sized independent venue in Sydney learned the hard way that even a packed house can lead to losses if the deal is wrong. Eager to land a buzzy international indie band, they agreed to a hefty flat guarantee of A$30,000 – a figure the band’s agent insisted on due to strong social media buzz. The venue had never paid that much for a 1,200-capacity show, but they gambled that a sellout at A$35 per ticket would cover it. The show did sell out, but just barely – and after marketing costs, the venue actually netted around A$28,000 from ticket sales. They ended the night in the red by a couple thousand dollars, essentially paying for the privilege of hosting a full house. What went wrong? They let hype cloud their financial judgment. In hindsight, the venue manager admitted they should have pushed for a versus deal – perhaps A$20k vs 85%. Had that been in place, the artist would still get their ~A$28k (85% of net) from the near-sellout, and the venue wouldn’t have lost money. The lesson: no matter how excited you are about an act, run the numbers conservatively. Guarantees that look achievable on paper leave zero margin for error. One illness, one bad weather night, or even slightly higher expenses can tilt a thin margin into a loss. Now, this Sydney venue has a policy of never offering a guarantee that exceeds 80% of expected net income for the show. If an agent demands more, they counter with a vs deal or politely pass. It’s tough turning down a hot act, but as the owner put it, “We can’t survive on bragging rights. We need at least the chance of profit.”

Lesson 2: The Versus Deal Lifesaver

Contrast that with a story from a 500-cap UK club that credits a versus deal with saving their skin on a tour stop. The club booked an American alt-rock band whose streaming numbers were strong, but it was the band’s first UK tour. The agent wanted a £5,000 guarantee, anticipating a quick sellout at £15 a ticket. The club’s promoter, however, was unsure – the band had no UK radio play and it was a Tuesday night gig. They negotiated it down to £3,000 vs 70% of net ticket sales. Sure enough, when the night came, only about 200 people showed up (many fans didn’t realize the band was in town, as it turned out). Gross ticket sales were roughly £3,000. After minimal expenses, 70% to the band was around £2,000 – but the guarantee was £3,000, so the band still got their minimum. The venue lost a bit on the show (around £1,000 out of pocket to cover that guarantee plus costs), but imagine if they had agreed to the original £5k guarantee – their loss would have tripled. In this case, the versus deal was a lifesaver, limiting the downside. The band appreciated not walking away empty-handed, and the club didn’t take a catastrophic hit. Interestingly, the band’s agent later told the promoter, “I’m glad we went with the versus. Next time we’ll build the show up more.” When the band returned a year later, the groundwork from that first show paid off – they drew 400 people and the deal (again a versus, slightly higher guarantee) ended up paying the band above the minimum and netting the club a small profit. The moral: for developing acts or uncertain markets, versus deals protect relationships. No one feels cheated – the artist got a fair shot at money, and the venue lived to book another day. It builds trust that you’re a venue that wants the artist to succeed but won’t recklessly overextend.

Lesson 3: Rentals – Short-Term Gain, Long-Term Pain?

A large concert hall in California had an experience that highlights the pros and cons of full rentals. The hall, about 2,500 capacity, mostly books its own shows but occasionally rents to outside promoters. A new promoter offered to rent it at a premium price for a Latin pop concert. They agreed on a $15,000 flat rental fee + costs, which was well above the hall’s usual rent – the promoter was confident due to the artist’s popularity. On paper, this was great for the venue: guaranteed income and someone else taking all risk. They staffed up, provided the space, and indeed the show sold out, with the promoter grossing around $100,000 in ticket sales. But come show day, it became clear the promoter had oversold VIP packages, and also hadn’t hired adequate security for the enthusiastic crowd. The venue’s team had to scramble to maintain safety and ended up opening extra balcony seating to accommodate VIP ticket holders that shouldn’t have been sold. The event was chaotic. While the venue made its $15k and extra on bar sales, the patron experience suffered, and their facility endured more wear-and-tear than a typical night (seats were damaged in the rush, etc.). The promoter made a hefty profit but hadn’t managed the crowd well. The hall management faced angry emails from some attendees over the disorder, despite not being the show’s promoter. This story underlines a hidden cost of rentals: loss of control. A venue’s reputation can still be affected by a rented event’s outcome. The hall has since adjusted its rental contracts to require more direct coordination on crucial aspects like security and crowd management, even if it’s not their show – effectively, they insist on approving the promoter’s operational plan or providing those services for an additional fee. They also realized that while a fat rent check is nice, it can pale in comparison to a share of a hugely successful show. If they’d co-promoted on a 80/20 split, the venue might have earned $20k+ that night instead of $15k, and arguably could have ensured smoother operations. Finding the right balance is key. Now they evaluate each outside rental not just on fee, but on promoter track record and potential upside. Sometimes they counter a rental inquiry with a co-promotion offer – lower upfront fee but a revenue split – if they believe in the show. In this case, the promoter wasn’t interested in sharing, so rental was fine, but the hall learned to protect its brand even when handing over the reins.

Lesson 4: Building Trust Through “Good” Settlements

A positive example comes from a theatre in Germany that turned settlement into a relationship-building moment. They hosted a mid-level artist on a 75/25 split deal after costs. The show sold better than expected, so the artist was due a nice payout – in fact, about €2,000 more than their highest guarantee offer on that tour. At settlement, the venue’s accountant carefully went through every line with the artist’s tour manager, down to receipts for catered dinners and the venue’s marketing expense. The tour manager was impressed by the thoroughness, but what really floored them was this: one of the equipment rentals came in €300 under the estimate, and the venue chose to give that €300 as additional payout to the artist, since it was technically part of the net income. (They could have quietly kept it, as the artist didn’t know the budgeted figure, but the deal was after actual expenses, so it rightly belonged in the split pool.) The tour manager remarked that in some places, they wouldn’t even see that detail – “they’d just pocket the difference.” This act of honesty reinforced that the venue was treating the artist as a true partner. The agent later told the venue booker that the act was so pleased with how they were treated financially and personally that they wanted to prioritize that theatre on the next tour. This goes to show, settlements done right lead to repeat business. The artist felt valued and trusted the numbers, and the venue cemented a reputation for fairness. It’s not about that €300 – it’s about the principle. Many seasoned promoters will pay a little extra here or there (or not charge every conceivable fee) when they want to invest in a long-term relationship. It’s very much like customer service – a small gesture can create loyalty that’s worth thousands in future shows. In 2026, with artists communicating directly with fans and each other more than ever, being known as “a venue that won’t rip you off” is a competitive edge that no marketing budget can buy outright.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a versus deal in music booking?

A versus deal pays the artist a guaranteed minimum fee or a percentage of ticket sales, whichever is higher. This structure balances risk by providing the artist a safety net while allowing them to share in the upside of a successful show. It is commonly used for mid-level artists or uncertain markets.

How do revenue split deals work for venues?

Revenue splits, or “door deals,” pay artists a percentage of ticket sales, such as 80/20, after expenses are covered. This low-risk structure scales the artist’s pay based on attendance, ensuring venues aren’t stuck paying large fees for empty rooms. They are ideal for grassroots venues and developing artists.

When should a venue offer a flat guarantee to an artist?

Venues should offer flat guarantees primarily for “must-book” artists with proven drawing power, like Friday or Saturday headliners. Because the venue pays a fixed fee regardless of ticket sales, this high-risk structure requires confidence that gross sales will meet or exceed the guarantee to avoid financial losses.

What is a promoter profit deal in concert booking?

A promoter profit deal ensures the promoter receives a fixed profit margin, typically 15% of expenses, before sharing remaining revenue with the artist. The artist receives a guarantee plus a split of the overage only after costs and this built-in promoter profit are covered. It is common for high-stakes arena shows.

What are the benefits of a four-wall venue rental deal?

Four-wall rentals provide venues with low-risk, guaranteed income through a flat rental fee paid by an external promoter. The venue acts as a landlord, avoiding the financial risk of ticket sales while often retaining ancillary revenue like bar sales. However, the venue forfeits any profit share from a sell-out event.

How does the show settlement process work?

Show settlement occurs after the event when the venue and artist representative reconcile ticket sales and expenses. Both parties verify gross revenue, deduct agreed costs like production or marketing, and calculate the final payout based on the contract terms. Accurate data and receipts are essential for a smooth, transparent transaction.