Understanding Artist Riders in 2026

Touring artists in 2026 arrive at venues with detailed rider documents that spell out everything they need for a successful show. These riders come in two parts – one covering technical production needs, and another for hospitality requests off-stage. For venue operators, deciphering these demands is a critical skill. It’s about balancing what the artist needs to shine on stage with what the venue can realistically provide. A rider might ask for specific sound equipment, stage layouts, catered meals, or even quirky personal items – and decoding these requests means understanding which are mission-critical and which are simply preferences.

Technical vs. Hospitality: The Two Sides of a Rider

Every artist rider has two key sections, each serving a different purpose. The technical rider lays out production requirements: sound system specs, lighting design, stage plot diagrams, input lists for instruments, backline gear (like amps or drum kits), power supply needs, and sometimes crew and security provisions, which are essential for coordinating with artists’ production riders. Think of it as the blueprint for the performance itself – ensuring the artist’s show can be delivered as envisioned. On the other hand, the hospitality rider details the comfort and care of the artist and crew off-stage: catering (food and drinks), dressing room setup, towels, transportation, hotel rooms, and other personal comforts, requiring close collaboration between artists and talent agents. These two halves together form the complete rider, and savvy venue managers read both closely to prepare a smooth event, especially when the rider calls for specific personnel.

It’s important to grasp that technical and hospitality needs often interplay. For example, if a band’s tech rider specifies an extended soundcheck in the afternoon, the hospitality rider might request snacks available at that time for the hungry crew. By viewing the rider holistically, venue operators can anticipate logistics – having both the right gear on stage and the right support backstage at every step.

The Purpose Behind the Requests

Riders sometimes get a bad reputation as lists of extravagant diva demands, but the truth is most requests have practical roots. The wildest anecdotes (like bowls of M&Ms with certain colors removed or rooms repainted in odd colors) stick in public memory, but they’re the exception as green riders give artists leverage to make meaningful changes. In reality, an artist’s rider is more like a playbook for delivering their best performance through smooth event planning practices. For instance, a singer asking for throat-coat tea or a specific brand of sports drink isn’t about luxury – it’s to protect their voice and energy through the show. A guitarist requesting a particular type of guitar strings or amplifier settings is ensuring the sound is just right for the audience.

Boost Revenue With Smart Upsells

Sell merchandise, VIP upgrades, parking passes, and add-ons during checkout and via post-purchase emails. Increase average order value by up to 220%.

Famous stories illustrate why riders matter. The legendary “no brown M&M’s” clause in rock band Van Halen’s 1980s rider is a classic example of backstage practices that build loyalty. The band wasn’t being frivolous; that odd request was a test to confirm venues had read every detail. If brown candies were found backstage, it signaled the crew that the venue might have overlooked more crucial technical instructions – like stage weight limits or wiring requirements – which could be dangerous, highlighting why artist hospitality builds loyalty. In other words, meticulous fulfillment of even quirky details can prevent bigger problems by indicating the venue’s attention to the entire rider. Experienced venue managers know that honoring the spirit of a rider builds trust with artists. It shows the venue is detail-oriented and professional, which ultimately makes touring acts more comfortable and confident on show night.

Evolving Trends in 2026 Riders

Artist riders are not static – they evolve with the times. In 2026, several new trends are influencing what artists ask for. Health and wellness have become priorities: the old clichés of junk food and Jack Daniels backstage are out, while green smoothies, high-protein snacks, and herbal teas are in, reflecting modern backstage hospitality practices. Many artists now request organic meals or vegan catering options as standard. You might see a juicer or blender on a hospitality rider, or a request for a quiet meditation space instead of buckets of beer. This shift reflects a generational change: today’s performers often prioritize fitness and mental well-being on tour, knowing it improves their shows.

Another 2026 trend is the rise of “green” or sustainable riders – artists using their leverage to reduce the environmental impact of their tours. Beyond just personal health, they’re thinking about planet health. It’s increasingly common to see requests that no single-use plastics be provided, that catering be locally sourced and organic, or that recycling and compost bins be available backstage. Some major tours even include carbon offset provisions or ask venues about renewable energy usage. We’ll explore sustainability riders in depth later, but the key point is that artists in 2026 are bringing values into their requests – from eco-friendliness to inclusivity. For example, some riders now specify diversity or sensitivity considerations, like providing gender-neutral dressing rooms or ensuring local crew are briefed on any cultural needs the artist has.

Crucially, budget sensitivity is also on the radar. Post-pandemic, many artists understand that venues, especially independent ones, are operating on thin margins. This means some are open to more flexible or modest riders when playing smaller rooms – as long as their core needs are met. As we decode the modern rider, remember that it’s a two-way communication. It’s the beginning of a conversation where artists say “This is what will help us put on a great show,” and venues have the opportunity to reply “Here’s how we can make that happen.”

Navigating the Technical Rider Requirements

The technical rider can run several pages long and is often dense with specs and jargon. It’s essentially the tech blueprint of the concert, and decoding it is critical for a smooth performance. Venue operators must ensure they understand every line: from the number of monitor mixes on stage to the exact power amperage needed. Below, we break down key components of technical riders and how to handle them without blowing the budget.

Stage Plots and Input Lists

At the heart of every technical rider is the stage plot – a diagram outlining how the stage should be laid out for the performance. This visual map shows where each band member stands, where each instrument and amplifier goes, and where equipment like mic stands, drum risers, or DJ tables should be placed. Alongside it is usually an input list, detailing every audio input that needs to be patched into the sound system (for example, “Input 1: Kick drum mic,” “Input 2: Snare mic,” “Input 3: Guitar DI,” etc.). These documents tell your production team exactly what to set up.

For venue tech crews, the stage plot and input list are a starting checklist. A best practice is to cross-reference these with your in-house inventory. Do you have all the microphones and DI boxes listed? Enough mic stands and cables? Is your stage large enough to accommodate the layout? For instance, if the plot shows a five-piece band with a grand piano but your stage is tiny, you may need to communicate stage dimensions and propose a tighter layout. Advancing these details early – meaning, discussing them with the artist’s production manager a few weeks before the show – prevents nasty surprises on show day, a process known as technical advancing for festivals. Many veteran production managers will send updated stage plots once the tour is underway, so always get the latest version and clarify any unclear items (better to ask what “extra riser for guest” means than guess and get it wrong).

Budget tip: You don’t have to buy every piece of gear that every artist’s input list demands. If the rider calls for six high-end vocal mics but you only own four, see if the band can bring their own, or arrange a short-term rental or borrow from a friendly local venue. Often, touring bands carry some of their specialty gear – they might actually prefer to use their own vocal microphones or DI boxes. Communication is key: confirm what you can provide in-house and what they’ll bring. This way you spend money only on truly needed rentals.

Ready to Sell Tickets?

Create professional event pages with built-in payment processing, marketing tools, and real-time analytics.

Sound and Power Specifications

Quality sound is non-negotiable for artists, so technical riders usually spell out detailed sound system requirements. This can include the minimum PA power (wattage and coverage for the room), the mixing console preferences for front-of-house (FOH) and monitors, and the number of monitor wedges or in-ear monitor systems needed on stage. Don’t be intimidated if a rider says something like “Professional 3-way active PA with 4 subs per side” or requests a specific console model (“Midas M32 or equivalent”). These are guidelines to ensure the artist’s mix will be clear and punchy. If your venue has a solid installed system, provide the full specs to the artist’s team during the advance – you might be surprised how often it is acceptable even if it’s not the exact brand named.

Perhaps the most critical (and sometimes overlooked) element is power requirements. Big tours can carry massive lighting rigs, LED walls, and high-powered amplifiers that draw serious electricity. The rider should indicate how many circuits or how much amperage is needed (e.g., “2 x 200A three-phase drops” or “at least 4 separate 20A circuits for audio, lighting, backline, etc.”). Never ignore these numbers – nothing will grind a show to a halt faster than a power outage mid-set, proving that infrastructure is the new headliner. Ensure your venue’s power distribution can handle the load. If not, consider renting a generator or additional distro, or work with the tour to scale back some elements. In 2026, fans and artists alike expect uninterrupted power and flawless sound at shows, requiring upgrades to festival basics, so double-check things like backup power for the mixing console and that you have clean, hum-free circuits for audio gear.

One cost-effective strategy is standardization of your house sound setup. If you invest in a flexible, rider-friendly console (many mid-size venues choose popular digital boards that most engineers know how to use) and a solid PA system, you’ll meet most rider specs with minimal extra cost. Many artists will adapt to your in-house system if it’s of professional quality, even if it’s not exactly what’s on their wish list. Communicate your specs clearly: send tech packs to the tour that list your sound equipment. If you proactively answer their concerns (“Our venue has a 32-channel Soundcraft Vi console and a 20,000W PA with front fills and four monitor mixes available”), you often head off potential demands for rentals. Transparency builds confidence that the venue can deliver.

Lighting and Visual Effects

Modern concert productions – even at the club level – often come with elaborate lighting and visual requests. A technical rider might include a lighting plot or at least a description of the desired atmosphere (“moody blue wash on stage, 4 moving head spotlights, ability to black out between songs,” etc.). Larger tours could ask for things like followspots trained on each member, strobe lights, haze or fog machines, LED video panels, or even laser effects. As a venue operator, parse these requests and see what you have in-house. Do you have any intelligent lights or moving heads? A spotlight in the balcony? Perhaps you don’t own LED walls, but the artist is bringing a video screen – in that case, your job is ensuring you have space and power for it.

Smooth Entry With Mobile Check-In

Scan tickets and manage entry with our mobile check-in app. Supports photo ID verification, real-time capacity tracking, and multi-gate coordination.

For lighting, a common budget-friendly approach is to provide a good basic stage wash and a few versatile fixtures, then let touring acts bring any specialty lights they need. Ensure your power grid can supply lighting without causing audio interference (LED walls and lights can introduce noise on power lines – separate circuits help). If a rider calls for a specific lighting console or lighting designer access, coordinate early. Sometimes tours travel with their own lighting console and just need to hook into your dimmers and circuits. In other cases, they might ask you to hire an experienced lighting operator who knows a certain system. Plan for that labor cost if needed – or negotiate if it’s outside your budget.

Special effects like fog machines, pyrotechnics, or confetti cannons are a red flag area for both budget and safety. Many small venues simply cannot accommodate pyro or haze due to fire codes and ventilation. If an artist requests something like cryo jets or small fireworks, you must evaluate it against your building’s regulations and insurance. Safety always comes first – no show is worth an unsafe condition. Most artists understand this. If you have to say no to a pyro request, propose a safe alternative if possible (e.g., CO2 jets, which create a visual plume without flame, or a confetti drop). There are creative ways to achieve a “wow” effect without violating codes. One venue manager recalled an artist asking for open-flame pyrotechnics in a historic 300-capacity theater – the venue had to decline for safety reasons, but they worked with the artist to substitute a dramatic CO2 blast timed to the finale, illustrating best practices for smooth event planning. The result still thrilled the crowd, and it was all cleared with the fire marshal in advance. Always loop in local authorities for special effects and get everything in writing if you agree to a modified plan.

Grow Your Events

Leverage referral marketing, social sharing incentives, and audience insights to sell more tickets.

Backline Equipment and Instruments

The backline refers to the instruments and amplifiers that the band uses on stage – typically items like guitar amps, bass cabinets, drum kit, keyboards, etc. Depending on the tour, the artist might carry all their own backline, or they might ask the venue to provide some or all of it. A technical rider will list what’s needed. For example: “One professional drum kit (5-piece, maple shells) with hardware and Zildjian cymbals” or “One Fender Twin guitar amp, one Ampeg SVT bass amp with 8×10 cab.” If you’re a large venue or one with a house backline, you may already own some common pieces to satisfy these. Smaller venues often do not keep a full backline – in those cases, you’ll be arranging a rental or borrowing from a local music company or another venue.

When faced with backline requests, prioritize and negotiate. High-ticket or rare items like a concert grand piano or vintage keyboards can be very costly to rent and transport. If a jazz artist demands a grand piano but you’re a tiny club, see if an electric stage piano would be acceptable as a substitute – often it is, if discussed honestly. For bands, if they ask for two full-stack guitar amps but your stage (and budget) can only handle one, let them know your limitations well in advance. Many times the touring production will adjust – perhaps they’ll bring an extra amp themselves, or scale down the stage plot for your room. It’s amazing how flexible even big acts can be when you’re upfront and work together on a solution. The key is never showing up on show day hoping they won’t notice something missing. They will notice, and it risks derailing the show and your relationship. Instead, if your venue doesn’t have a specialty item, contact local rental companies early for quotes. You might also coordinate with other venues on the tour circuit – for example, if an artist needs a specific keyboard for three shows in your region, sometimes venues share the cost to rent one and transport it between them. This kind of creativity can save each venue money and still give the artist what they need.

Also, pay attention to spare needs on the rider. Some meticulous riders request spare guitar strings, drum heads, or batteries for pedals. These are usually inexpensive requests intended to avoid show-stopping issues. Having a pack of the right strings or some 9-volt batteries on hand is a small cost that can rescue a performance if something breaks. It’s worth the minor expense – and it shows the artist you’re on top of the details.

Crew and Staffing Requirements

A technical rider sometimes extends beyond gear into personnel. Artists might specify certain crew roles they need at the venue. Common examples: a monitor engineer, a front-of-house engineer (if they aren’t traveling with one), a lighting operator, spotlight operators, stagehands for load-in and load-out, riggers (for hanging trusses or heavy lighting), or even security for the backstage. These requests ensure the artist has enough qualified hands on deck to execute the show. As a venue, you should assess what staff you have in-house and what you might need to hire in. If you’re a small venue, you might wear multiple hats (the house sound tech might also handle monitors, for instance). For larger shows, you may need to call in extra hired guns or work with local stagehand unions.

Be mindful of local labor regulations and unions. In many major cities (and particularly in large arenas and theaters), union labor rules will govern how you staff the event. This can affect costs – for example, unions often have minimum crew calls (you pay for a minimum number of hours even if work finishes sooner) and overtime rules. Venues in cities like New York, Chicago, London, or Sydney know that strong union presence is a reality, and you must budget for urban premiums accordingly. If an artist’s rider asks for a specific union crew (say, IATSE stagehands or Teamsters for heavy trucking), coordinate with the local union hall well in advance to secure the labor and understand the costs. Never surprise an artist by being short on crew – if they requested four loaders to help unload the truck and you only have one venue janitor available, that’s a serious problem. It’s better to invest in a few extra hands for a night than to keep a touring crew waiting (or worse, make the artists themselves help haul gear, which sets a very poor tone).

One area often mentioned in tech riders is security staff – e.g., a request for a dedicated security guard at the stage door or an escort for the artist when moving through public areas. This is about safety and comfort. Even if you’re a tiny club, if the rider asks for someone to guard the dressing room, try to assign a trustworthy staff member to that duty. It can often be your existing bouncer or a manager doubling up, but make sure it’s covered.

Finally, integrate the tech requirements with a timeline. Many riders include a sample schedule: load-in time, soundcheck time, doors open, showtime, etc. This helps you plan staff shifts. If you see “Load-in: 3:00 PM” on the rider, you know your stage and sound personnel should be ready by then, and any rented gear should arrive before that. Good scheduling in line with the rider avoids overtime costs – if you know soundcheck is at 5:00 PM, you won’t call your crew at 10:00 AM unnecessarily (or conversely, you won’t call them too late and blow past doors trying to finish setup). Aligning your team’s schedule with the artist’s plan is a budget-friendly move that also demonstrates professionalism.

Below is a quick-reference table summarizing common technical rider requests and cost-conscious ways venues can accommodate them:

| Technical Request | Typical Example | Budget-Friendly Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High-channel-count mixing console | Rider asks for a 32+ channel digital desk for FOH. | Provide your in-house 32-channel console if you have one and verify it meets their needs. If they insist on a specific model you lack, rent it for the day or see if the tour can carry their own. Communicate with the tour’s audio tech about console compatibility. |

| Powerful PA system with subs | Rider specifies a concert-level PA, e.g. “Professional 3-way system with subwoofers”. | Use your installed PA and detail its specs in advance. If it’s underpowered for a particular show, supplement with an extra subwoofer stack rental rather than renting a whole new system. Often just a bit more low-end can satisfy the requirement. |

| Specific backline instrument | e.g. “Nord Stage 3 keyboard, Fender Twin amp, 5-piece drum kit with Zildjian cymbals.” | Check what you can source locally. Partner with a backline rental company or borrow from a nearby venue. If you own similar gear (older model keys or a different amp), offer it as a substitute – many artists will accept an equivalent if it’s in excellent shape. |

| Additional stage crew (hands, techs) | “2 stagehands for load-in/out; 1 monitor engineer; 1 spotlight operator.” | Tap your existing staff who have the skills (many audio techs can also run monitors). Bring in freelance techs for the day if needed – it’s cheaper than overworking a tiny team. If budget is tight, discuss scaling down (maybe the tour’s own crew can operate lights if you cannot staff it). Always ensure at least minimum crew for safety (don’t skip on stagehands if heavy lifting is needed). |

| Extensive lighting effects | “Intelligent lighting with 8 moving heads, hazer, 2 followspots.” | Provide a basic stage wash and a few effects lights that you have. Communicate what’s in-house (many mid-size venues have some LED PARs or a couple moving heads). If followspots are requested but you have none, see if simply keeping a static front light on the performer will suffice. Most artists adjust if they know in advance. For haze, use venue-friendly hazers (water-based) if allowed by fire code, or skip it and let the tour know. |

Mastering the Hospitality Rider

If the technical rider is about what it takes to make the show happen, the hospitality rider is about keeping the artist and crew happy, healthy, and comfortable before and after the show. Hospitality requests can range from the very simple (“bottled water and towels”) to the very specific (“a hot organic meal for 10 people, served at 6 PM, with vegan and gluten-free options”). For venue operators on a budget, the goal is to meet the artists’ genuine needs thoughtfully without unnecessary extravagance. Many successful venues, even small ones, have learned that you can delight performers with creativity and care more than with money. Let’s break down common hospitality elements and cost-effective ways to handle them.

Catering and Dietary Needs

Food is at the heart of hospitality. After long drives or flights, many artists arrive at a venue quite hungry (often having skipped decent meals), so they pay close attention to catering. In 2026, expect to see detailed dietary requests in riders. Healthier eating is the norm: you’ll see riders specifying organic ingredients, vegetarian or vegan meals, dairy-free or gluten-free options, and an emphasis on freshness. High-sugar junk food trays are being replaced by things like hummus and veggie platters, mixed nuts, protein bars, and fresh fruit, which are staples of artist hospitality in 2026.

Don’t be intimidated by a rider’s culinary specifics. Use it as a guide to show you care. If the rider asks for a hot meal for 8 people with vegan options, that doesn’t mean you must hire a gourmet chef. Local restaurants and caterers can be your best friends. Many venues strike a deal with a nearby eatery to cook band meals at a reasonable rate, a strategy for delighting performers and building loyalty – for example, a family-owned Italian restaurant might be thrilled to deliver pasta, salad, and bread for your artists in exchange for a mention or tickets. This can cost a fraction of formal catering. Some venues provide meal “buyouts” (a fixed cash stipend) so artists can purchase their own food, but often artists appreciate a thoughtfully arranged local meal more than cash. As long as the food is tasty, on time, and meets their dietary needs, you’ve succeeded.

Pay special attention to allergies and dietary restrictions listed. If one band member is celiac and requires gluten-free food, double-check that any provided meal or snack truly is GF (sometimes that means reading labels or informing the restaurant). If a crew member is vegan, ensure there’s a filling plant-based protein in their meal, not just salads. One veteran venue operator suggests always having at least one vegetarian option on hand, even if not asked – someone unexpected might be vegetarian, and it prevents anybody from going hungry.

Also consider cultural dietary needs if you’re hosting international artists. For example, a metal band from the Middle East might have Halal dietary requirements. It goes a long way to avoid offending by simply not providing pork products and respecting cultural dietary laws if you’re aware of such needs. Similarly, during periods like Ramadan or other fasting times, understanding the timing of meals (e.g. offering food after sunset) can demonstrate exceptional hospitality. These kinds of gestures, which cost little or nothing, signal respect for the artist’s background.

Finally, timing is everything with catering. Note the schedule: if soundcheck is at 5:00 PM and doors at 7:00, the band likely wants to eat around 6:00 PM. Make sure hot food arrives on time (and not hours early getting cold). Coordinate with the tour manager about when they prefer to eat and any day-of changes. Being punctual and flexible – for instance, if they’re running late, having snacks to tide them over – shows professionalism. And always have some backups: keep quick snacks like fruit or energy bars around in case a meal is delayed. A well-fed artist is a happy artist, and happy artists give better shows.

Beverages and Refreshments

Drinks are a staple of hospitality riders, and the requests can be very specific about brands and types. Common items include bottled water (often a certain brand or type like sparkling vs. still), coffee and tea, perhaps a selection of soft drinks or juices, and a modest amount of alcoholic beverages like beer or wine. When an artist requests a particular brand (say, a French mineral water or a local craft IPA), it’s ideal to fulfill it, but acceptable to substitute a similar option if that exact brand is unavailable – as long as you communicate the swap in advance. Honesty is important: if an imported brand isn’t sold in your country, let them know and ask if a local equivalent is okay. 9 times out of 10, it is.

For alcohol, know your artist. Some artists are completely sober and their rider will explicitly say “No alcohol in dressing room.” Always respect that – it could be for personal or recovery reasons. Others might request a specific liquor or a certain number of beers. Provide what’s asked within reason, but you don’t need to overstock. If they say “a bottle of quality local red wine,” you can find a nice mid-range bottle from a local vineyard that won’t break the bank, rather than feeling obligated to buy a pricey Premier Cru Bordeaux. In fact, adding a local touch – “We got this wine from a vineyard 10 miles away” – can turn a budget-friendly choice into a special gesture.

One trick venues use is bulk buying beverages. If you see riders consistently requesting, say, sparkling water or a particular soda, buy in bulk from a wholesaler. It lowers the cost per show. Non-perishables like bottled drinks, beer (if you have storage), and even things like chips or candy (if still requested) can be bought in warehouse quantities and used across multiple events. Just keep an eye on expiration dates and store them properly.

An emerging trend is providing healthier beverages: Kombucha, coconut water, electrolyte sports drinks, and non-alcoholic craft beers are more common in green rooms now. While some of these can be pricey at retail, again consider local or generic brands. Many health beverage startups love exposure – a local kombucha brewery might cut you a deal or even sponsor your backstage if you consistently stock their drinks for artists. Don’t overlook the basics though – plenty of artists still appreciate a hot cup of coffee or English Breakfast tea upon arrival. Invest in a decent coffee maker and kettle for your venue. A fresh pot of coffee and a selection of teas (including herbal) ready when the artist loads in is a low-cost hospitality touch that scores big points.

Backstage Comfort and Ambience

Walking into the dressing room or green room, an artist should immediately feel at ease. Comfort, cleanliness, and privacy are the pillars here. Riders may specify things like: a certain number of clean towels (for post-show), a mirror (with lights for makeup, etc.), garment racks for stage clothes, a sofa or comfortable chairs, and perhaps ambience requests like scented candles or flowers. These are all about creating a temporary “home away from home” for performers who are on the road, emphasizing comfort, cleanliness, and privacy. The good news is that most comfort items don’t have to cost much – it’s more about effort and thoughtfulness.

First, cleanliness is paramount. A hospitality rider might not explicitly say “clean the room,” but if you deliver a dirty, cluttered, or smelly backstage area, no fancy snacks will overcome that bad impression. Make sure the dressing room is thoroughly cleaned: floors vacuumed, surfaces wiped, no sticky residue from last night’s party. Put yourself in the artist’s shoes – would you want to relax here? A clean, tidy space with some fresh air or a mild air freshener (nothing too strong or allergenic) is the baseline. It’s often said in venue management that cleanliness is free – it costs next to nothing except staff time, yet it’s often the biggest differentiator in artist comfort, as low-cost touches matter.

Now consider the amenities. Does your backstage have a private bathroom or at least easy access to one? If yes, stock it with basic toiletries (soap, toilet paper, perhaps travel-size deodorant or mouthwash if you want to go the extra mile). If no private bathroom, at least ensure the public one is very nearby and exceptionally clean and stocked during the artist’s stay (and maybe designate it temporarily for artist/crew use only). Provide enough clean towels as requested (always have a few extra; they’re cheap and any not used can be saved for the next show if washed). If the rider requests something like a full-length mirror or steamer for clothes, these are one-time purchases that can be reused by your venue – worth having on hand.

For ambience, small touches help: many riders list a preference for soft furniture, lamps instead of harsh overhead fluorescents, and even decorations like a few plants or local art. You don’t need to refurnish your green room for each show, but keep it well-maintained. A trick some venues use is adjustable lighting – having a dimmable lamp so artists aren’t stuck under glaring lights. If an artist has a specific request like “room to be at 22°C” (yes, some do specify temperature!), try to accommodate by adjusting the thermostat in advance. Privacy and security also fall under comfort: ensure that random staff or fans don’t wander backstage. Many riders will explicitly state that the dressing room should be off-limits except to approved personnel. Honor that by briefing your staff and perhaps putting a sign on the door. Artists appreciate knowing they can leave their personal items and relax without interruption, allowing staff and security to be invisible.

Finally, consider “extras” that make the space nicer without much money: a Bluetooth speaker for them to play music, a phone charger station (multiple types of cables), and maybe a small basket of “necessities” (like earplugs, tampons, Band-Aids, pain reliever, etc.). These are inexpensive but cover common needs. One venue became known for always placing a couple of humorous local postcards and a mini guide to the city’s late-night food in the dressing room – a charming personal touch that touring bands mentioned fondly. The bottom line is: invest thought into the room itself, not just the consumables. A little effort making the space comfortable can leave as big an impression as any fancy rider item.

Quirky and Special Requests

Over the years, artists have become famous (or infamous) for the bizarre requests that occasionally pop up in hospitality riders – the “brown M&Ms” type of clauses and beyond. In truth, these quirky requests are relatively rare, but when they do appear, they can make a venue operator scratch their head. Examples might include a specific brand of extremely hard-to-find imported candy, a request for a local team’s hockey puck as a souvenir, a particular scent of incense to be burned, or a cardboard cutout of a cartoon character (yes, these have all happened!). The key to handling oddball requests is not to panic and not to mock. Often, there’s a reason behind them, even if it’s just to make the artist feel “at home” or to inject some fun into a long tour.

If you encounter a strange request, evaluate it seriously: is it feasible, safe, and affordable? If it’s something inexpensive and harmless – fulfill it. Getting 100 black balloons or a vintage Nintendo setup might be weird, but if you can do it for a few dollars or via a quick Amazon order, why not? It can become a talking point and show the artist you really care. Many veteran venue operators have stories of turning a strange rider item into a memorable moment. For instance, one act’s rider asked for a small custom local souvenir for each band member. The venue hit up a nearby gift shop and gave the band funny t-shirts from the city – the band loved it and wore them on stage that night.

However, if the quirky request is cost-prohibitive or impossible, approach it diplomatically. Say a rider asks for a very costly bottle of champagne or a brand of juice that’s not sold in your country. Rather than simply ignoring it, communicate with the tour manager: apologize and explain the situation (“XYZ brand isn’t available here, but we can provide ABC which is very similar – would that be okay?”). Usually they’ll understand or might even say the item isn’t a big deal. Occasionally, tours include an outrageous item intentionally as a test or a running joke. By acknowledging it and doing your best, you’ve passed the test. If you truly can’t do it, sometimes the tour will carry the item themselves (some mega artists travel with trunks of their favorite snacks anyway and only include it on the rider in case). The worst approach is to say nothing and hope they don’t notice the omission – that breeds resentment. Always address it one way or another.

One tip: maintain a sense of humor and goodwill. If a request is clearly tongue-in-cheek (some artists write silly things in riders to see if anyone is reading), you can respond in kind. There’s a story of a venue that found a request for “one snowman (made of real snow)” in a summer tour rider – the savvy venue manager printed a picture of a snowman and left a note, “Our snowman melted, please accept this portrait instead.” The band got a kick out of it. That venue proved they read the rider thoroughly and had a bit of personality too. It became an anecdote the artists shared positively with others in the industry.

In short, treat quirky requests as an opportunity to shine rather than a nuisance. When you fulfill an unusual ask, you often create a memorable experience for the artist. These little things can set your venue apart. There are legendary tales of artists remembering venues that went the extra mile on something small – like sourcing a birthday cake for a band member’s surprise backstage, proving small details make a big impact or setting up a “zen room” with cushions and dim lighting for an artist who meditates. Those acts of hospitality, while not expensive, become the stories artists and their teams tell others: “That venue really took care of us.” And in a touring community where word travels fast, that’s pure gold for your reputation.

Transportation and Lodging (When Included)

Not every hospitality rider will cover ground transport or hotels – often those are handled in the main contract or by the promoter. But especially for smaller-scale tours or one-off events, you might see notes about transportation (“provide a van and driver for airport pickup”) or lodging (“two double hotel rooms for one night”). If your deal with the artist includes these, you’ll want to fulfill them cost-effectively. Many venues build relationships with local hotels to get preferred rates for artist accommodations. A nearby boutique hotel might offer you a discount or trade (you mention them as a partner in exchange for a free room) – don’t be afraid to negotiate. For ground transport, if it’s a simple pickup and drop-off, sometimes using a rideshare or taxi service is cheaper than hiring a car and driver. Just be sure it’s reliable and that someone is clearly assigned to manage it (an Uber showing up at the right time and place, with a large enough vehicle for gear, etc.). Communicate pickup details clearly to the artist’s team.

If a rider doesn’t explicitly mention hotels or travel, double-check the main contract or advance notes. You don’t want to be the venue that forgot to book the hotel that was promised. Conversely, if you’re not providing lodging but the artist assumed you were, that’s a potential conflict – clear it up before they arrive, possibly by offering guidance (“We don’t have hotel in our offer, but if you need recommendations, we partner with Hotel X with a discount code”). In any case, treating artists’ travel and lodging professionally – even if it’s just pointing them to a safe place to park their tour bus – is part of holistic hospitality.

Let’s summarize some common hospitality rider requests and smart ways venues can meet them without overspending:

| Hospitality Request | What It Often Entails | Budget-Friendly Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Hot meal for band & crew (e.g. 10 people) | A specific dinner, often with dietary variations (vegan, etc.), at a set time. | Partner with a local restaurant for catering – e.g., arrange trays of a hearty meal that fits their diet. Or provide a meal buyout (cash) if that’s more practical, letting them choose. Ensure timing and quality over sheer cost – a simple homemade-style meal served hot can beat an expensive one served cold. |

| Assortment of snacks and drinks | Items like chips, fruit, candy, bottled water, soft drinks, tea, coffee, alcohol (beer/wine) – sometimes specific brands. | Stock up on common requests in bulk (cases of water, etc.). Substitute with local equivalents for import brands (with approval). Provide a mix of healthy snacks (fruit, nuts) alongside any fun snacks. For alcohol, buy just what’s needed; a local craft beer can satisfy a “12 beers” rider item with local flair. |

| Clean towels and toiletries | Many riders request X number of clean bath towels, plus sometimes things like soap, tissues, etc. | Use a towel service or buy a big stock of cheap but decent towels you can wash and reuse. Always exceed the number requested by a few. Place basic toiletries (travel-size shampoo, etc.) if showers are available. These items are low-cost but high-impact for comfort. |

| Backstage ambiance (furniture, climate, decor) | Making the room comfortable: chairs/sofa, mirror, proper lighting, a certain temperature, perhaps flowers or candles. | Keep furnishings clean and in good repair – maybe add a second-hand comfy couch and a lamp to soften the room lighting. If candles or flowers are specifically requested, inexpensive options from a grocery store will do (or LED candles). Pre-set the thermostat if you know their preferred temperature. It’s the thought that counts more than designer decor. |

| Special/quirky item (one-off requests) | Could be anything from “local sports team merchandise” to a rare snack or an instrument for backstage jam. | Assess cost: if cheap, just do it. If expensive or not available, find a close substitute or locally-flavored alternative and inform the artist in advance. Often a thoughtful replacement (with a note explaining it) will be appreciated. For odd requests like games or decorations, see if staff can bring from home or borrow – creativity solves a lot. |

Negotiating and Managing Rider Expectations

Reading an artist rider is one thing; negotiating and managing it is another crucial skill. Especially when budgets are tight, venue operators need to know how to prioritize essential elements and tactfully handle or modify the rest. The secret to rider management is proactive communication. Here we’ll cover how to discuss riders with artists and their teams, where you have flexibility, and how to protect your venue from unreasonable costs or risks while still delivering a great experience for the talent.

Early Communication and Advance Discussion

The moment you receive a rider (often weeks or months before the show), read it thoroughly and identify any challenges. The earlier you flag potential issues, the more cooperative artists and agents tend to be when you use best practices for collaboration. Reach out well in advance to the tour manager or agent with pertinent questions or to seek clarity. For example, if the rider mentions “venue to provide 3 phase power” and you’re unsure of your electrical setup, ask your production manager to verify and then confirm with the tour what you have. It’s much better to discover now if something might be a problem than on the day of show.

When something in the rider is beyond your capacity, start the conversation early. Most artists and agents are reasonable if you communicate proactively and have a plan. Perhaps your venue doesn’t have an in-house washer/dryer but the rider asks for same-day laundry – you could contact the tour and say you don’t have laundry on-site, but you can arrange for a laundry service in town if needed, or offer a small stipend for them to use at their hotel. By addressing it early, you show professionalism and avoid disappointment later. Early negotiation might also reveal that some requests are not as firm as they look; tours often copy-paste riders from bigger shows to smaller ones, and they might say “Oh, don’t worry about that item for this date.” You won’t know unless you ask.

One useful strategy is to include the rider as part of the contract when you confirm the show, but with amendments as needed. Make sure any changes you agree on (like “artist will bring their own backline amplifiers” or “venue to provide catering buyout of $200 instead of hot meal”) are documented in writing, a key part of managing riders effectively. This protects both sides. The contract can reference the attached rider and explicitly list approved modifications. Then there’s no confusion on show day – everyone has the same expectations. It’s common for a hospitality rider to be adjusted for smaller venues; just be upfront and get that edit approved. Many agents appreciate a venue that says, “We saw the request for a grand piano. We don’t have one but can rent an electric keyboard – would that be acceptable? If so, we’ll note that in the contract.” It’s far better than staying silent and hoping the artist doesn’t really need a piano (a risky gamble you’re likely to lose!).

Prioritizing Must-Haves vs. Nice-to-Haves

Not all rider elements carry equal weight. Part of decoding a rider is understanding which items are must-haves (critical to the performance or artist’s well-being) and which are nice-to-haves (items that would be nice but the show can go on fine without them). In negotiations, focus on guaranteeing the must-haves first. These typically include all crucial technical components – appropriate sound and lights, essential instruments, power, a safe and private space, hydration and some food for the artists, etc. If an item directly affects the quality of the show or the artist’s basic comfort, it’s usually non-negotiable. For instance, if an EDM artist’s tech rider says they require a subwoofer that can hit certain low frequencies for the bass drop, you need to make sure your system can deliver that or arrange one that can – otherwise the artist can’t deliver the show the fans expect.

On the flip side, many hospitality rider requests fall into the nice-to-have category, even if they’re very specific. Artists will survive if they don’t get their preferred brand of organic peanut butter, but they won’t perform well if you fail to provide any water or if the stage sound is terrible. So allocate budget and energy accordingly. One effective approach is to confirm the critical needs and politely inquire about flexibility on the rest. You might say to the tour manager, “We will absolutely have plenty of vegetarian food and the equipment you listed. There are a couple of items we’re having trouble sourcing in our area – would substitutes be okay?” By showing you’re fully on board with the important stuff, you build goodwill that can make them more relaxed, ensuring you don’t promise everything and under-deliver.

During the advance process, ask the artist’s team if there are any priority items on the hospitality rider. Sometimes they’ll tell you without prompting (“Artist X really needs a humidifier in the dressing room because of their voice – it’s crucial”). That helps you focus. They might also say “Don’t worry if you can’t find item Y, it’s not a big deal,” which instantly relieves you of that burden. You can even provide a short rundown of what you plan to fulfill and see if they object. For example: “We plan to stock local craft beers since your requested brand isn’t sold here, and we’ll get an assortment of teas including chamomile and peppermint as listed. Does that cover everything for drinks?” This gives them a chance to affirm or adjust, and then you’re set.

Remember, transparency and honesty go a long way. If your budget is genuinely constrained, it’s okay to (tactfully) let the artist know you’re a small independent venue and you’ll do your absolute best with the resources at hand. Most artists started in the small club circuit and are human beings who don’t want to sink a beloved venue financially over a bowl of expensive guacamole. They’d rather you stay open to host them next time. Just don’t use that as an excuse to skimp on essentials – use it as context when negotiating luxuries.

Offering Smart Substitutions and Solutions

When you can’t meet a rider item exactly as written, the next best thing is to offer a smart substitution that achieves a similar result. The cardinal rule here is to maintain the spirit of the request. If an artist asks for a particular French cheese that you can’t find, providing a high-quality local cheese of a similar type (and saying so) is a thoughtful substitution. If they wanted a specific brand of high-end vodka that’s out of stock, you might provide another top-shelf vodka, rather than a cheap one, to show you take their preferences seriously.

We’ve touched on many substitutions already: local beverage brands for requested ones, electric piano for acoustic piano, etc. The key is communication – never swap something without letting them know ahead unless it’s truly last-minute and there’s no choice (and even then, apologize and explain). In many cases, the artist will pre-approve alternatives. For example, a DJ’s rider might list a very particular mixer model that you can’t get – if you offer a comparable model and explain it’s the best available locally, almost all will accept it. They might even be carrying their own small gear to adapt.

For hospitality items, think creatively. Homemade or personal touches can sometimes substitute for expensive items. If a rider asks for an “assortment of fresh baked goods from a bakery” and your budget is slim, maybe your team can bake a batch of cookies or buy decent ones from a grocery store bakery and plate them nicely. The artist may not know the difference, or if they do, they might appreciate the down-to-earth approach. One tour might request a juicer machine backstage – if you can’t buy one, maybe you arrange a fresh jug of smoothie from a local juice bar as an equivalent. Again, it’s about meeting the underlying need: in this case, a healthy energy boost.

Where things get tricky is if an item has technical or safety implications. Always consult with the artist’s team before substituting in that realm. For instance, if they requested a certain type of microphone and you want to use a different model, run it by them – because that could impact their sound. Usually, substitutions of equal or higher quality are fine; it’s substituting lower quality that can cause friction. Even then, honesty is the best policy. If you truly can’t do it, tell them what you do have and ask if it will get the job done. Many times the answer is “yes, that’s okay.”

Keep a list of common substitutions that have worked for you. Over time, you might find that 90% of riders ask for the same general things, and you will have go-to solutions: e.g., Requested import beer -> provide a similar local craft beer; Expensive brand snacks -> provide a known high-quality alternative; Full drumkit request -> provide your house kit with new drumheads. As long as you maintain quality and communicate, you’ll save money by not chasing every exact item to the ends of the earth.

One more tip: sometimes the solution isn’t a substitution, but a buyout or omission with permission. For example, if the rider asks for five types of fresh juice and you have none, you might ask “Would it be acceptable if we provide a $50 rider credit so you can purchase preferred juices en route or have them delivered?” Some artists are fine with that because it simplifies their day – they get the cash and can decide for themselves. This is essentially a courteous way of saying “we can’t do this, but we’ll compensate you so you can.” It should be a last resort (it’s always nicer if you handle it), but it’s better than doing nothing.

Setting Boundaries: Safety, Legal, and Budget Limits

On rare occasions, an artist’s rider might contain something truly outside the bounds of what’s safe, legal, or financially feasible. Examples could include pyrotechnics in a non-permitted venue (as discussed earlier), requests that violate alcohol laws (like serving minors, which you obviously cannot do), or extraordinarily costly demands such as structural modifications to the venue. It’s crucial for venue operators to know where to draw the line and how to convey that firmly yet amicably.

Safety is the absolute line in the sand. If a request would jeopardize anyone’s safety or violate fire codes, you must say no – nicely, but unequivocally. Explain the reason briefly (“Due to fire regulations, we cannot allow any open flame or fireworks, but we can explore safe special effects alternatives for you”). Most artists and their teams will immediately understand. If they push back (which is unlikely for legitimate safety issues), stand your ground and reference the law or code. Your venue license and insurance depend on compliance, so there’s no wiggle room there. In fact, many seemingly “demanding” artists include potentially unsafe stuff just assuming venues will handle the permits or say no. For instance, a big act might have an arena-sized rider that mentions pyro; when they play a smaller venue, they know it probably won’t happen, but they send the full rider anyway. Use your judgment and don’t be afraid to protect your house.

Legal or regulatory issues might include noise curfews (e.g., no loud music after 11pm by city ordinance) or labor law constraints. If a rider asks for something that would break local law – like exceedingly high dB levels or going past curfew – discuss it with the tour. Sometimes they aren’t aware of local rules until you tell them. Perhaps you can apply for a waiver with the city or agree on adjusting set times slightly. If a show must end by 11pm due to law, then it must – and you need to plan the schedule accordingly, even if the rider imagined a later end.

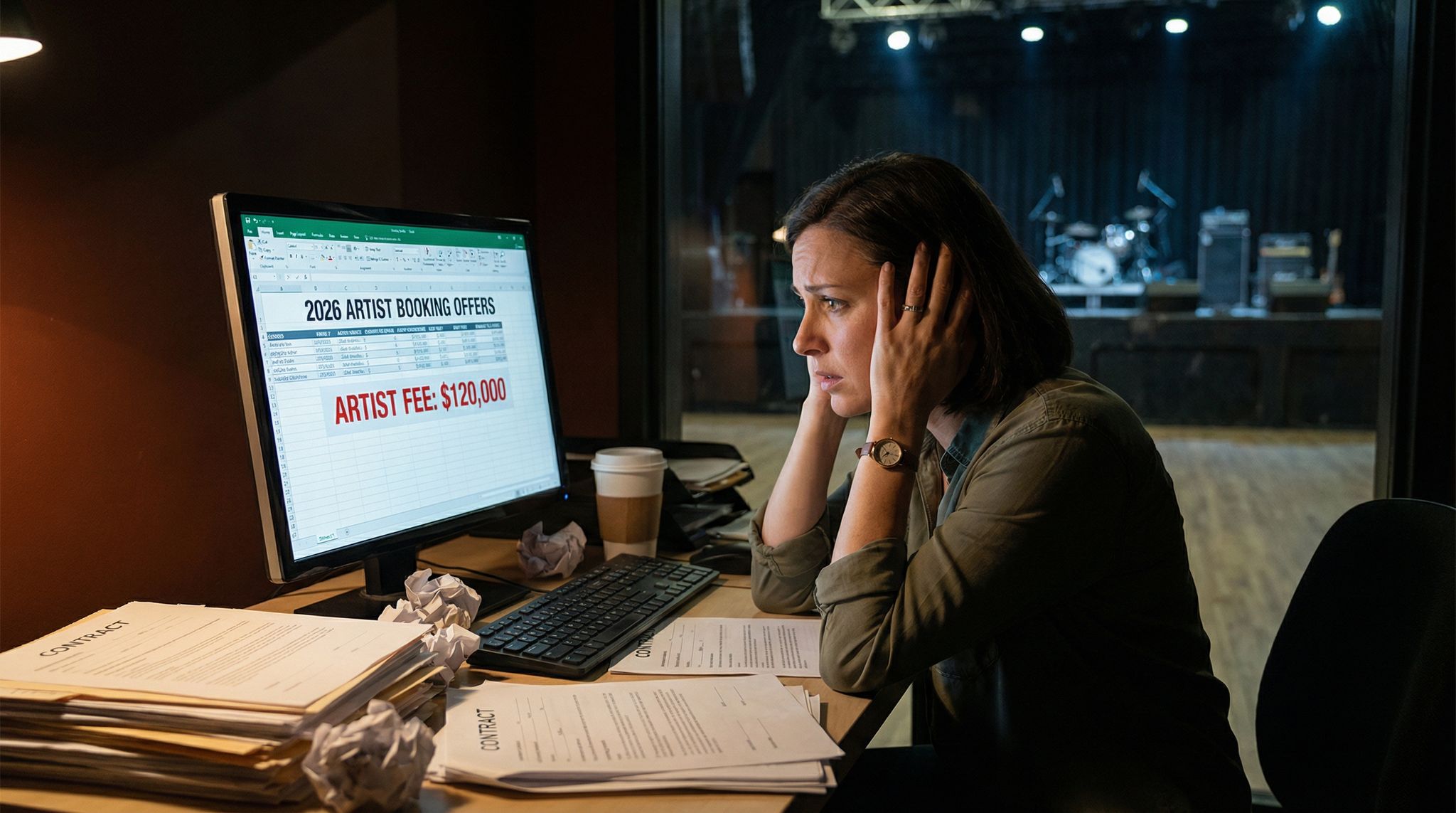

Budget is a softer boundary but still real. There may be cases where fulfilling one line in a rider costs more than the entire fee you’re paying the artist. That’s not sustainable. A common example is hospitality for large entourages – if an artist rolls in with 20 people and expects full dinner for all, but your deal’s economics never accounted for that, you need to renegotiate. It’s fair to have a conversation like, “We can cover catering for 8 people as agreed. If you have 20, perhaps we could do a simpler meal, or the extra meals would need to be at your cost.” Often, artists are fine paying for extra mouths to feed if it’s beyond the norm – they just need to know in advance. This is where having a hospitality budget cap in your deal memo helps (“hospitality budget not to exceed $X without prior approval”). Many promoters include that, and if the rider would blow it, they go back and adjust the deal or the expectations.

Handling these boundary issues always comes down to clear, polite communication. You can be firm without being unfriendly. Emphasize that you want to provide a great experience, and that’s why you need to make certain adjustments. One venue manager shared a smart phrasing: instead of saying “we can’t afford that”, say “here’s what we can comfortably do within our resources – let’s find a solution that works for everyone.” This keeps the focus on problem-solving rather than just refusal.

And absolutely, get any agreed deviations in writing (email is fine) and ideally reflected in the contract or advance sheets. If you’ve agreed “no pyrotechnics” or “sound must stay under 100dB because of local ordinance” or “band will handle their own dinner beyond 5 people,” make sure those points are noted in the final tech/hospitality advance document everyone has. That way on show day the touring party isn’t blindsided by a restriction the agent or manager okayed weeks ago but forgot to tell them. It also protects you if later someone says “but the rider promised this.” You can point to the correspondence or revised contract clause. It’s all part of managing expectations, which is the core of rider negotiations.

Documenting and Confirming Changes

After you’ve done the work of negotiating any changes or substitutions to the rider, the last step is to document everything clearly. Send a polite, itemized email or document to the tour manager (and copy the booking agent if appropriate) summarizing what will be provided and noting any agreed exceptions. For example:

- “Per our discussion, Venue will supply a Yamaha digital piano in lieu of the acoustic piano. Artist will bring their own guitar amplifiers, as agreed.”

- “We will have all the requested beverages except Brand X coconut water, which is unavailable here – we’ll provide Brand Y as a substitute (approved by Tour Manager on Jan 10).”

- “Open flame pyrotechnics are not permitted, so we will instead provide a CO2 effect for the finale, per our agreement.”

This kind of confirmation not only prevents misunderstandings, it shows the artist’s team that you are organized and on top of things. Always encourage them to review it and let you know if anything is misconstrued. It’s much easier to correct course on an email than on a show day.

On the day of the event, have the final agreed rider (with any changes) printed out on hand for your crew and hospitality team. Everyone should be working off the same playbook. If the artist’s entourage is large, it can help to also brief the key staff: e.g., “We aren’t doing the sushi platter that was in the original rider, they opted for pizza instead and that’s arriving at 5pm – so nobody freak out that there’s no sushi.” Consistency is key so the artist doesn’t get mixed messages.

By managing expectations through documentation, you also set yourself up to potentially get feedback. A professional tour manager will appreciate an end-of-day check-in: “Was everything per the advanced plan to your satisfaction?” If something was missed, you’ll hear about it and can address it for next time. But ideally, there are no surprises – you under-promised and over-delivered.

One more thing: don’t ignore the rider fine print. Many riders include pages of legal addendums (insurance requirements, merchandise split details, etc.). Make sure those are also agreed upon and documented. Some hospitality riders include notes like “if any item is missing, promoter agrees to a deduction of $$ from fee.” You want to avoid those penalties by either fulfilling the item or negotiating that clause out beforehand. That all comes out in the advance and documentation phase. With a clearly managed rider, you free the artist to focus on the show – and you free yourself to focus on executing it rather than scrambling for last-minute fixes.

Sourcing Hard-to-Find Items and Smart Substitutions

Even with the best planning, there will be times a rider asks for something that isn’t easy to get – at least not without hefty cost. Maybe it’s an unusual piece of gear, a rare food item, or just a large quantity of something your venue doesn’t stock. This is where the ingenuity and network of a venue manager come into play. How do you track down that specialty guitar pedal or that case of gluten-free craft beer that the artist loves? And if you truly can’t find it, what are the smart substitutions that keep the artist happy anyway? In this section, we share strategies for sourcing and substituting like a pro, all while watching the bottom line.

Leveraging Local Vendors and Partnerships

One of a venue’s secret weapons is its local community and vendor network. Savvy venue operators cultivate relationships with all kinds of local businesses – restaurants, grocery stores, bakeries, breweries, music shops, rental companies, hotels, you name it. When a tough rider request comes in, these relationships can save the day (and the budget). For instance, suppose an artist requests a lavish cheese platter with a dozen specific cheeses. Instead of running to an expensive gourmet importer, you might partner with a local deli or cheesemonger who can assemble a fantastic platter at cost or in exchange for some concert tickets. Local businesses often love the idea of being involved with a cool show or famous artist, and they may offer you discounts or special service for the privilege.

Many independent venues have a go-to neighborhood restaurant that helps with artist catering. As mentioned before, you might negotiate a standing arrangement: the restaurant provides dinner for every show’s headliner at a fixed price per head, possibly promoted as “Official Catering Partner of XYZ Venue.” This saves you the hassle of finding a new caterer every time. Likewise, a local craft brewery might supply a few cases of beer for your backstage in exchange for a mention on social media or some signage, creating a cost-effective hospitality partnership. It never hurts to ask – the worst they can say is no, and often you’ll find enthusiastic partners.

Think beyond food and drink. Is there a boutique hotel that might occasionally upgrade artists to a suite at a standard room rate because they like being known as the artist hotel in town? Does a car service or rideshare fleet owner want to be the “official transport” for artists and give you better rates? Even services like a local massage therapist or yoga instructor could be part of your extended network – some venues arrange for perks like a quick massage for band members upon arrival, provided free or cheap by a local practitioner who just wants a free concert ticket and a photo with the artist, as partnering with local businesses can enhance the experience. These creative partnerships dramatically reduce your costs while simultaneously delighting artists with something unique.

A great example comes from a mid-sized venue that had a modest hospitality budget. They struck a deal with a nearby Italian restaurant to deliver trays of hot pasta, salad, and bread for every show’s backstage dinner, utilizing a restaurant to supply artist meals. It cost much less per person than catering from a big company, and artists loved it because it felt home-cooked. Another venue partnered with a local fitness center: if artists wanted to work out or shower at a full gym, the venue provided day passes courtesy of the gym, which can show care for artist wellness. In return, the gym got some promotion through social media shoutouts. These kinds of community-based solutions enrich your offerings at minimal expense.

The takeaway: map out potential allies in your city. When a strange or challenging request pops up, brainstorm if any local business might have a win-win solution. Need a vintage record player and vinyls for a backstage lounge vibe (yes, some riders ask for that)? Maybe the local record shop can lend one in exchange for a shout-out. Need 20 pounds of ice at 11pm? The convenience store next door might let your staff grab it from their machine if you’re friendly. Being resourceful and having a Rolodex of contacts is often more valuable than a big bank balance.

Creative Substitutions for Unavailable Items

Despite best efforts, you’ll occasionally hit a wall finding an exact item. Perhaps it’s out of season, out of stock, or unheard of in your region. This is where you apply the art of equivalent substitution. We touched on this in negotiations, but let’s delve into examples. Imagine the rider requests a specific brand of kombucha that is only sold in California, and you’re in Singapore. You’re not flying kombucha across the world. Instead, find a locally loved kombucha – ideally a premium one – and provide that. The key is to match the category and quality, if not the brand. In your communication, you might even frame it as introducing them to a great local product (“We couldn’t get ‘HealthyGut Kombucha’, but we have this amazing local brew kombucha for you to try – we think you’ll love it.”). Now it doesn’t feel like a compromise, it feels like a discovery.

For gear, say the rider asks for a particular model of guitar amp that you can’t secure. Substitute with the closest comparable amp you have or can get – same power, similar tone – and let the guitarist or their tech know in advance what you’re providing. Often, touring musicians are gear nerds and will say “that’s fine” or request a tweak. For example, “If you can’t get a Fender Twin Reverb, a Vox AC30 will do.” They might even prefer something once they know it’s available. In many cases, artists list a gold-plated ideal but have a backup in mind. By proposing the backup yourself, you make their life easier.

Another creative approach is fulfilling the function of a request in a different way. If the rider bizarrely says “room must be filled with fresh yellow flowers,” and it’s the dead of winter with no flowers around, what’s the function? Possibly to create a bright, cheery vibe or a certain scent. You might instead decorate with yellow fabric or lights, or place a bowl of lemons (a bit of humor and yellow color and scent of citrus) and explain the flower situation. It shows you made an effort to honor the request’s spirit. Will that satisfy every artist? Not all, but many will appreciate the attempt and chuckle at the creativity.

Some substitutions can be upgrades or personal touches that cost little. A famous example: an artist requested a specific high-end tea brand. The venue couldn’t find it, so their hospitality manager, who was an amateur herbalist, made a custom blend of herbal tea for the artist with a nice note. The artist actually loved it and later asked for the recipe. Turning a failure to source into a special gesture flipped the script entirely. Use caution here – you need to be sure the substitute is high quality and safe (allergies! don’t experiment with unknown substances in food/bev). But if you have a particular skill or local specialty, it can substitute for a generic rider item. Instead of imported Belgian chocolates you can’t afford, maybe you put locally-made artisanal chocolates that are excellent. It’s the quality and thought that counts.

Finally, have a backup plan for truly critical needs. If the rider says “2 Wireless handheld mics” and yours die on the day, know where you can borrow or rent last-minute. Keep emergency phone numbers (rental shops, techs, even other venue managers) for mutual aid. In the live events world, there’s often a camaraderie – if you urgently need a certain cable or piece of hardware, a neighboring venue or production company might lend it if they’re dark that night. Build those relationships by being helpful yourself when others call.

Renting, Sharing, and Buying Wisely

For infrequent but important needs, renting can be a lifesaver. It often makes more sense to rent a $5,000 keyboard for a day at $200 than to purchase one and have it collect dust most of the year. Identify reputable rental companies in your area for backline, AV, and hospitality equipment. Build a rapport with them; sometimes they’ll offer a venue rate or last-minute help if you’re a regular client. Keep in mind, however, rental costs can add up, so use carefully – ensure it’s either covered in the deal or truly necessary to avoid a show cancellation or major compromise.

In some local circuits, venues engage in resource sharing. Especially among grassroots venues that aren’t directly competing (or even if they are, sometimes solidarity wins), there might be an informal network where you can ask, “Hey, does anyone have an extra amp tonight?” One venue might lend another a drum stool or mic cable in a pinch. This requires trust and reciprocity – always return what you borrow and be ready to lend when others are in need. Independent venue associations, like NIVA in the United States or Music Venue Trust in the UK, have fostered a cooperative spirit. Tap into those communities for sourcing help; someone might have exactly the item you need on standby.

When it comes to purchasing items, be strategic. If an element keeps appearing in riders and you find yourself scrambling or renting repeatedly, consider buying it outright for your venue. This goes for both technical gear and hospitality appliances or kit. For example, many riders require a basic steam iron or garment steamer for wardrobe – if you don’t have one, you can buy one for under $50 and it will pay for itself after one or two shows by saving time and fulfilling the rider. Similarly, if every other rider wants a specific type of DI box or microphone, owning one might be worthwhile so you’re always ready. Do this for items that have broad use (a good quality DJ mixer, a couple of wireless mics, a vegan-gluten-free snack assortment in your storage) rather than one-offs.

Another trick: buy used or on sale for rider needs. Thrift stores for furniture (that cozy couch or mini-fridge for backstage), eBay or local music shops for second-hand gear (that particular guitar pedal might be half-price used), or clearance aisles for hospitality items (stock up on that brand of chips when it’s on sale in bulk). Just ensure used equipment is tested and reliable – no point in a cheap amp that fails mid-show. For hospitality, no one minds if the fridge is second-hand, as long as it’s clean and works.

One area to be cautious: don’t cut corners on quality for core items. If an artist needs a certain caliber of monitor speaker or a certain grade of food, giving them a subpar version to save money can backfire if it affects the show or makes them ill. Save costs smartly, not blindly. Provide filtered water rather than tap if the rider says “bottled water” and you want to avoid plastic – fine. But don’t provide warm unfiltered tap water in reused bottles – that’s not the idea. Likewise, a cheap knock-off guitar amp might literally not deliver the sound needed, whereas the real requested amp would. In such cases, it’s better to rent the real thing or be upfront about what you have and see if they accept.

Tapping into Industry Networks

Venue management can be a lonely job when you’re fighting daily fires, but remember you’re part of a wider industry network. Use it to your advantage for rider fulfillment challenges. Online forums or social media groups for venue professionals are a goldmine – you can post, “Has anyone sourced X item economically? How did you handle Y request?” and get answers from people who’ve been there. Other promoters and tour managers can also share tips on substitutions artists were fine with. For example, you might learn that “Artist Z’s favorite whiskey isn’t available outside Tennessee; we gave them Maker’s Mark and they were perfectly happy.” That’s insider knowledge that saves you time.

If you’re in an association like the International Association of Venue Managers (IAVM) or a regional group, attend workshops or chats about hospitality and production. You might pick up creative ideas, like how some venues partner with local farms for fresh produce (farm-to-backstage) which can actually be cheaper and impress artists. Or how venues are collectively fighting certain unsustainable practices by agreeing on standards (for example, some venues simply negotiate out expensive hard liquor requests for certain tour packages and collectively tell the agents “we don’t do that” – safety in numbers approach).

Some artists are now sharing their green and hospitality requirements publicly, almost as a point of pride. Organizations like REVERB (Music Climate Revolution) encourage artists to have sustainable riders and to work with venues on eco-friendly practices, finding a balance of flexibility and rigidity. By engaging with those initiatives, you might gain access to resources like guides on where to rent solar-powered batteries or how to source compostable dinnerware in your city.

Don’t underestimate your staff’s networks too. Your sound engineer might moonlight at a rental company, your bartender’s cousin might own a bakery, your security guard might have a friend with a van service. Let your team know what you’re looking for – sometimes an internal referral is the quickest fix. Just be sure to vet for reliability; keep the professional standards even if it’s a friend-of-a-friend helping out.

In summary, sourcing and substituting rider items on a budget is all about using your brains instead of just your wallet. By leaning on local partners, being creative with solutions, renting or buying smartly, and tapping the collective wisdom of other venue pros, you can fulfill even the craziest rider asks without breaking the bank. Often, the process of jumping through these hoops with ingenuity becomes part of the venue’s lore – and can even strengthen your relationship with artists (they see and remember how resourceful you were). Next, we’ll turn to a hot trend that intersects many rider requests: sustainability, and how venues are adapting to the new “green riders.”

Embracing Green and Sustainable Rider Requests

As the live music industry turns its focus toward sustainability in 2026, “green riders” have emerged as a game-changing trend. Many artists are no longer just asking for creature comforts – they’re using their riders to demand environmentally friendly practices at venues. This means as a venue operator you might see requests like “no single-use plastics backstage,” “catering must be locally sourced and organic,” or “provide recycling and compost bins.” While these requests come from a good place (who wouldn’t want less waste and a healthier planet?), they can present new challenges and costs. Let’s decode the common sustainable rider demands and discuss how venues worldwide are managing to go green without going into the red.

Ditching Single-Use Plastics

One of the most common green rider requests is the elimination of single-use plastic backstage – particularly water bottles. In the past, it was typical to stock cases of bottled water in dressing rooms and on stage for artists. Now, artists like Billie Eilish, Dave Matthews Band, and many others have taken a strong stance against that practice to advance causes they care about. They prefer refillable water solutions to cut down on plastic waste. Venues have adapted by installing water refill stations, providing pitchers of filtered water, or offering reusable bottles and cups. For example, the legendary Glastonbury Festival in the UK banned single-use plastic bottles entirely in 2019, preventing about 1 million bottles from being used in one weekend, a key step in greening festival artist hospitality. That set a precedent, and artists are pushing venues of all sizes to follow suit.

For a venue operator, the switch is quite feasible and can even save money over time. Instead of buying endless pallets of bottled water, you might invest once in a couple of large water coolers or dispensers. Some venues give each band member a branded reusable bottle as a welcome gift (bonus: a souvenir that also advertises your venue). You can also use recyclable aluminum cans of water as an interim step – many venues have moved to canned water, which is eco-friendlier since aluminum is easily recycled. The key is to ensure hydration is still convenient: make water readily accessible in jugs or coolers, have cups or bottles available, and let the artists know in advance that you’re complying with their green initiative. Most will cheer to hear “we’ve got refillable water coolers set up for you – no plastic here.” It aligns with their values and makes them feel heard.

Beyond water, consider other single-use plastics: utensils, plates, straws, cling wrap, etc. A green rider might request compostable or reusable servingware. This can be a bit more costly per unit (compostable plates vs. cheap paper/plastic ones), but it’s usually a marginal difference and increasingly expected. Buying in bulk can minimize the cost difference. If you run a venue kitchen or bar that feeds artists, switch to biodegradable or washable cutlery and dishes for backstage. Many venues have done away with plastic straws and instead have metal or paper ones on hand. These changes not only satisfy artists but can enhance your venue’s public image as well – fans notice when venues care about the environment, and heavy touring, road warrior acts often include instructions about the disposal of waste.

Sustainable Food and Beverage Choices

Another aspect of green riders is the push for sustainable catering. This goes beyond personal dietary needs into how the food is sourced. You might see phrases like “locally sourced produce where possible,” “all seafood must be sustainable,” or “organic ingredients preferred.” Artists who champion sustainability – perhaps inspired by organizations like REVERB or Julie’s Bicycle – want their tours to support eco-friendly food systems. For venues, this can mean adjusting your purchasing habits.

Locally sourced and organic food often does cost a bit more than mass-produced, shipped-in alternatives. However, it doesn’t have to break the bank. Work with your caterers or local suppliers to see what seasonal local foods are available – seasonal produce is usually cheaper and better quality. Instead of a generic fruit platter with out-of-season berries flown across the world, you could present ripe local fruits in season. It meets the sustainability ask and might even taste better. Some venues partner with local farms or farmer’s markets to buy produce in bulk for a run of shows, sometimes at a discount. In one example, Øya Festival in Norway committed to 100% organic, locally sourced catering for artists and crew, which became a point of pride for them, proving that going plant-based is viable. While a small venue can’t go that far overnight, you can start with small steps: maybe the bread and pastries backstage come from the bakery down the street rather than a big-box store; the coffee is fair trade and roasted locally; the cheese is from a regional dairy. These swaps not only reduce carbon footprint (less transport) but also ingratiate you with community businesses.

Another growing trend is plant-based meals. Even if an artist isn’t personally vegan, many green riders encourage offering more plant-based foods because they have a lower environmental impact than meat. If a rider doesn’t explicitly require only vegan food, you can still lean towards hearty vegetarian options to quietly meet the intent. This can also save money, as meat is often the priciest part of catering. One could serve a delicious veggie curry or pasta that satisfies everyone, with perhaps one token meat dish if needed, rather than a meat-heavy spread. If you do serve meat, sourcing from local, ethically raised providers checks the sustainability box (and tends to taste better, which the artists will notice!).

Keep in mind, any big shifts in catering should be communicated to the artist team. Don’t surprise a carnivorous band with an all-vegan menu unless it was requested – instead, highlight the sustainable elements of what you are providing. “We’ll be serving a mix of free-range local chicken and a vegan baked eggplant dish using produce from the city’s urban farm – hope that’s okay with everyone.” Framing it as a positive, rather than a forced sacrifice, makes it more palatable (literally and figuratively). And many artists are now expecting this kind of food; they’ve grown accustomed to it on tour, especially younger acts. You might find even if they didn’t ask, when you serve better, greener food, they love it.

Energy and Emissions: Greening the Production

Some green rider elements cross into technical territory: a focus on energy use and emissions. For example, an artist might request that the venue use renewable energy to power the show if possible, or they might travel with their own sustainable power source. Extremely eco-conscious tours (often by major artists) have asked venues if they can plug into the venue’s power grid instead of using diesel generators (to reduce emissions), or conversely ask if the venue has any solar or wind power. Coldplay famously invested in touring gear that includes portable solar/battery systems and even crowd-powered energy (dance floor tiles that generate electricity). While these are cutting-edge, it shows the mindset shift.