Introduction: A New Era of Venue Financing in 2026

Post-Pandemic Reality & Shrinking Margins

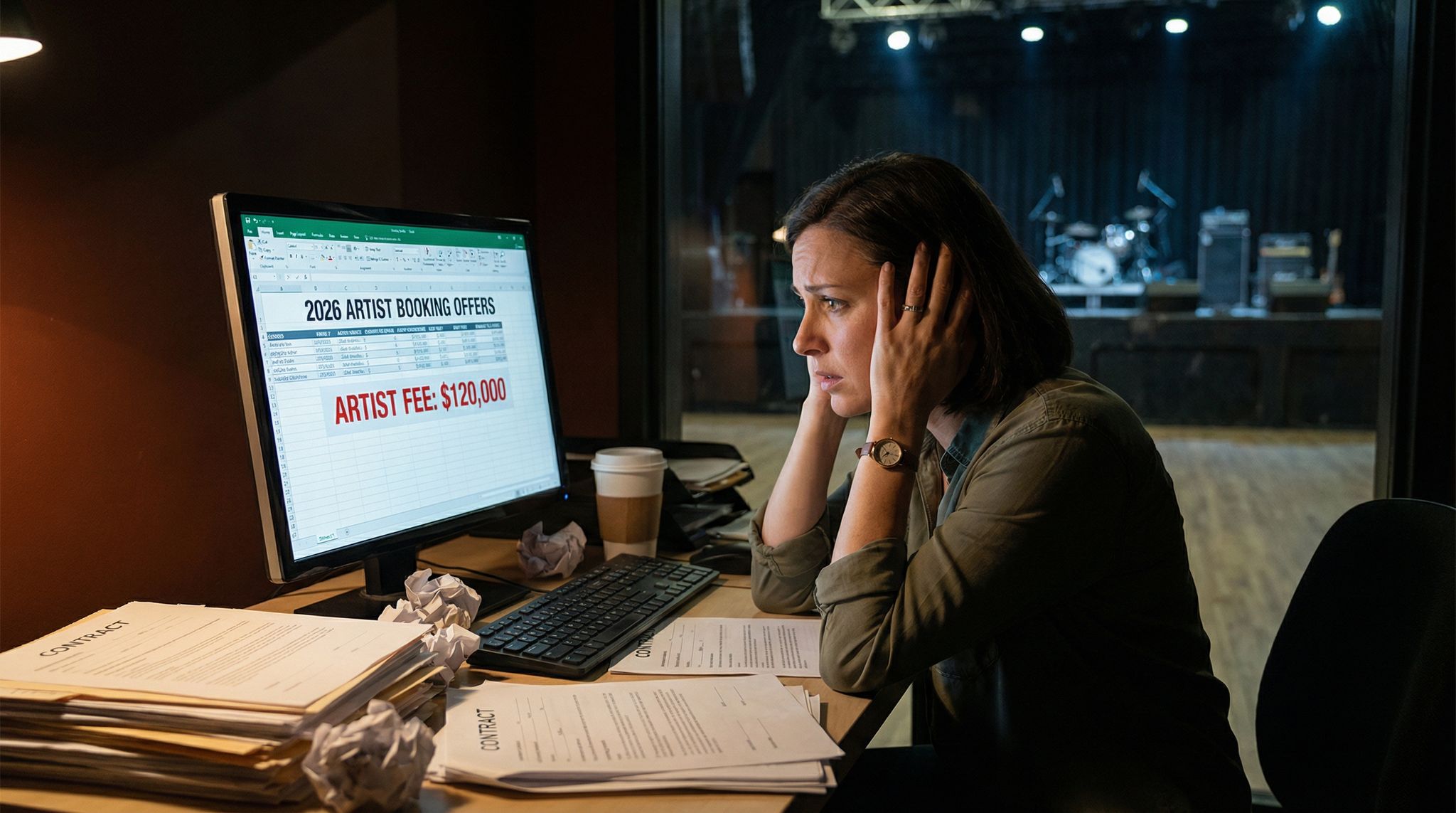

The live entertainment industry may be rebounding, but many venues are still on shaky financial ground. Independent venue profit margins have been squeezed to razor-thin levels – for example, grassroots music venues in the UK saw costs surge ~40% by 2022, leaving an average profit of just 0.2% of revenue (about £1,300 a year), necessitating data-driven financial planning strategies for venues. In the U.S., an industry survey found 64% of independent venues were financially unstable heading into 2026, a clear sign that budgeting beyond guesswork is essential. The situation is dire worldwide: the UK has lost a quarter of its clubs and late-night venues since 2020. These sobering figures underline why venues can’t rely on day-to-day cash flow alone to fund major needs.

With costs up and emergency grants exhausted, venue operators must seek fresh capital to survive and grow. Government rescue programs like the U.S. Save Our Stages grants or UK Culture Recovery Fund have long expired. Meanwhile, rising artist fees, energy bills, and staffing costs persist. Even sold-out shows and busy bars often barely cover operating expenses. Simply put, the old approach of “operate and hope there’s money left to reinvest” no longer works in 2026’s high-cost environment.

Why New Funding Is Needed Now

Beyond survival, venues also need capital to invest in their future. Upgrading aging sound systems, improving ventilation for health compliance, renovating worn-out facilities, expanding capacity, or even buying your building – all require upfront money that most venues can’t pull from their daily revenue. For instance, after the pandemic many venues spent heavily on safety and tech upgrades; those that couldn’t invest often fell behind. Staying competitive in 2026 means investing in better experiences and infrastructure, from updated acoustics to cashless payment systems, and that means raising capital.

Crucially, the alternative to smart financing is often closure or stagnation. Venues that lack funds for maintenance or improvements risk a downward spiral – declining audience experience, fewer bookings, and eventual shutdown. On the other hand, those that secure funding for strategic upgrades can boost their revenue potential (through higher ticket sales, VIP offerings, rentals, etc.) and future-proof their business. Financing isn’t just about survival; it’s about positioning your venue for long-term success.

Turn Fans Into Your Marketing Team

Ticket Fairy's built-in referral rewards system incentivizes attendees to share your event, delivering 15-25% sales boosts and 30x ROI vs paid ads.

The Strategic Scope of Venue Finance

At its core, venue finance is about much more than plugging operational deficits; it is the strategic management of capital to build long-term asset value. In my decades of operating rooms from intimate basement clubs to massive arenas, I’ve learned that treating your physical space as a dynamic financial instrument is what separates surviving from thriving. Effective venue finance encompasses securing capital for real estate acquisition, funding structural renovations, and optimizing your debt-to-equity ratio. This is fundamentally distinct from the day-to-day cash flow used for booking talent or buying bar stock. Mastering this broader financial discipline ensures your property remains competitive, compliant with modern safety standards, and resilient against unpredictable industry shocks.

Beyond Grants & Donations: Creative Capital Sources

In the past, struggling venues often turned to one-off fundraisers or arts grants. While helpful, these sources are limited and not guaranteed. 2026 demands a more proactive, entrepreneurial approach to venue financing. Venue operators are increasingly thinking like startup founders – pitching to investors, negotiating with banks, structuring creative deals – to inject capital into their operations. This guide will explore practical financing avenues beyond grants and nightly revenue: from traditional bank loans to private equity partners, sponsorship and revenue-sharing arrangements, and community-driven funding like equity crowdfunding.

Ready to Sell Tickets?

Create professional event pages with built-in payment processing, marketing tools, and real-time analytics.

Throughout, we’ll share real examples of venues worldwide that secured funding – and the lessons learned. Whether you run a 200-capacity indie club or a 5,000-seat theater, the principles of smart financing apply. The goal is to obtain the capital your venue needs without losing your soul or risking financial ruin. In the sections that follow, we break down each financing option with concrete tips and cautionary advice so you can confidently finance your venue’s future.

(Before diving in, ensure your venue’s basic financial management is solid – successful financing starts with good bookkeeping and budgeting. If you need a refresher on getting your financial house in order, check out our guide on data-driven financial planning strategies for venues to firm up your budget forecasts and revenue projections.)

Traditional Bank Loans: Borrowing for Your Venue’s Future

Preparing to Approach a Lender

For many venues, the most straightforward source of capital is a bank loan. To persuade a bank to lend you money, preparation is key. Start by getting your financial documents in impeccable order: profit & loss statements, balance sheets, cash flow projections, and tax returns for the past few years. lenders will scrutinize your venue’s financial health and trajectory. Venue operators should be ready to present a data-driven business plan that shows how the loan will be used and – most importantly – how it will be repaid.

Outline the specific project or goal for the loan (e.g. “$250,000 to renovate the auditorium and add 100 seats, which is projected to increase annual ticket revenue by $80,000”). Back up those projections with evidence: historical ticket sales data, market research on demand, and scenario planning. For example, if you plan to upgrade your HVAC system to improve air quality, show the rising client expectations post-COVID and how similar venues saw attendance or rental income increase after such upgrades. The more concrete and realistic your forecasts, the more confidence a lender will have. Using data-driven forecasting methods that top venues employ can strengthen your case to the bank. Also prepare a detailed budget for the project, so the bank sees you’ll spend the money wisely and not go over-budget.

Data-Driven Event Marketing

Track ticket sales, demographics, marketing ROI, and social reach in real time. Exportable reports give you the insights to make smarter decisions.

Just like an artist or promoter, venue operators must “pitch” banks by telling a story – but one rooted in numbers. Emphasize your track record: years in business, number of successful events hosted, community importance, and any assets or savings you can contribute. If 2024-2025 were rough, explain how you’ve cut costs or diversified income (perhaps by implementing strategies from your post-event debriefs or cost management efforts). Demonstrating that you run a tight ship operationally gives lenders comfort. Some veteran venue managers even share past post-event reports and debrief findings to illustrate their continuous improvement in operations and turnaround strategies for struggling venues. Overall, a clear narrative of stability, prudent management, and growth plans will make the bank far more likely to say “yes.”

Navigating Loan Options and Terms in 2026

Business loans come in many flavors. It’s crucial to choose a loan type and term that match your venue’s needs and cash flow. Common options include:

– Term Loans: A standard bank loan where you borrow a lump sum and repay in fixed installments (with interest) over a set period (e.g. 5, 10, or 15 years). Good for one-time big projects like a major renovation or purchasing your building. Tip: Match the term to the project’s useful life – you don’t want to still be paying off a loan in 10 years for equipment that will wear out in 5 years.

– Commercial Mortgage: If you’re looking to buy your venue’s property or refinance it, a mortgage loan uses the real estate as collateral. These often have 15-25 year terms. Owning real estate can stabilize your future (no landlord, and you build equity), but mortgages are substantial commitments. Consider if your venue can truly afford to “be its own landlord.” (For advice on weighing lease vs. buy, see A New Lease on Life: Negotiating Venue Leases – even if buying, you’ll need to negotiate with the seller or manage a lease during the loan process.)

– Business Line of Credit: Essentially a credit card for your business – the bank gives you a credit line (say $100,000) you can draw on as needed for working capital or smaller improvements. You pay interest only on the amount you use. This is helpful for short-term cash flow gaps or incremental upgrades. In 2026, with event demand fluctuating, a line of credit can be a lifesaver to cover offseason expenses or down payments for big shows.

– SBA-Backed Loans (U.S.): In the United States, check if you qualify for an SBA loan program, such as the 7(a) loan for small businesses. These loans are issued by banks but guaranteed up to 75-85% by the government, making banks more willing to lend, often with lower down payments. Similarly, other countries have development banks or cultural investment funds that partner with lenders to support entertainment venues – research what might exist in your region.

Grow Your Events

Leverage referral marketing, social sharing incentives, and audience insights to sell more tickets.

Be mindful of the interest rate environment in 2026. After the sharp rate rises of 2022–2024, global interest rates remain elevated but are stabilizing. That means loans will carry higher interest costs than the ultra-low rates of the 2010s, although forecasts indicate interest rates may slowly inch down in late 2026. Still, expect banks to offer small business loans with interest in the high single digits (exact rates vary by country). Always shop around and get quotes from multiple lenders – including local community banks or credit unions, which sometimes have more flexibility or interest in community projects than big banks. Also negotiate: if you’ve been a long-time customer or can offer stronger collateral, you might secure a better rate or terms.

Before signing, read the fine print on loan terms. Key points to clarify:

– Is the interest rate fixed or variable? Fixed gives stability (your payments won’t change), while variable could rise and strain your budget if rates climb. Many venue operators opt for fixed loans in uncertain times to avoid surprises.

– What collateral is required? Often, the loan will be secured by your venue’s assets – property, equipment, or a personal guarantee. Understand what’s at risk if you default. Try to avoid pledging collateral that would be catastrophic to lose (like your personal home) unless absolutely necessary. Some loans might be unsecured but will carry higher interest.

– Are there covenants? Banks sometimes impose conditions (covenants), like maintaining a certain liquidity or debt-to-income ratio, or restrictions on taking additional debt. Make sure any covenants are realistic for your business; if not, negotiate or find a different lender.

– Repayment schedule and penalties: Know when payments start, and if there are penalties for early repayment (or conversely, for late payment). Also check if the loan has a grace period until your project is completed (some lenders allow interest-only payments during a renovation period, for instance).

Collateral, Guarantees & Reducing Your Risk

Collateral is a big part of bank financing. Venues without a lot of assets often struggle here – a bank may ask for your business assets (sound equipment, lighting rigs, furniture) and/or personal assets (like the owners’ homes or other property) as security. It’s a tough decision: putting up collateral shows confidence and commitment, but it also means if things go south, you could lose critical assets. Only pledge what you’re prepared to risk. For example, using the venue’s equipment as collateral is common (since if you default, losing some gear is painful but not the end of the world), whereas using your family home is far more perilous.

One way to strengthen a loan application without risking more collateral is to find a guarantor. This is someone (or an entity) with strong finances who co-signs the loan, promising to pay if you can’t. A guarantor might be a financially solid business partner, a parent company if you’re part of a group, or even a supportive local authority or nonprofit in some cases. For instance, if your venue is municipally owned or partnered with a non-profit arts organization, that entity might guarantee a loan to help you secure better terms. Always get legal advice before signing a personal guarantee or asking someone to do so – it’s a serious obligation.

Another safety tip: borrow a bit less than the max you qualify for, if possible. It’s tempting to take the absolute maximum the bank will give, but remember you must service that debt in the years ahead. Leave yourself some breathing room. It’s often wiser to slightly scale back a project budget or supplement with other funding (e.g. raise some money from investors or sponsors, as covered later) than to end up over-leveraged with a huge loan. Many experienced venue operators suggest stress-testing your repayment plan: Can my venue still pay this loan if sales dip 20%? If the answer is no, consider borrowing less or on longer terms.

Example: Financing an Expansion with a Bank Loan

To see bank loans in action, consider a real-world scenario: a historic 500-seat theater that needed a major renovation in 2024. The owners wanted to upgrade the aging seating and acoustics, a project costing around $400,000. They secured a $300,000 bank term loan over 7 years to cover the bulk of costs, with the remaining $100,000 funded from their own reserves and a small local arts grant. The loan was secured by the venue’s building leasehold and assets (seats, sound equipment) and backed by a personal guarantee from the lead owner. By presenting a strong business case – including 5-year financial projections showing the new seats would allow higher ticket prices and more rentals, boosting annual revenue by an estimated $70,000 – they convinced the bank the upgrade would pay for itself.

Notably, the theater negotiated to delay repayment for 6 months (interest accrued but no payments) so construction could finish and shows could resume before debt service kicked in. This eased their cash flow during the dark period. The interest rate was fixed at 6.8%, keeping payments predictable at roughly $4,500 per month. Thanks to careful budgeting and an increase in ticket sales after reopening, the theater has been meeting its loan payments comfortably, validating the decision to borrow.

Bank loans aren’t just for big venues – even small clubs use them. During the pandemic recovery, a beloved 150-capacity club in Seattle took a $50,000 bank loan (backed by an SBA guarantee) to rebuild its stage and ventilation system, allowing it to reopen safely. The loan, repayable over 5 years, gave the club breathing room to welcome audiences back and generate the revenue to pay it off. On the flip side, we’ve seen cases where venues took on loans but didn’t see the expected revenue increase – those venues struggled or needed to explore additional turnaround strategies like implementing data-driven operational fixes to avoid default. The lesson: borrow based on conservative projections, not wishful thinking. If a bank loan is used wisely for a high-impact improvement, it can be a game-changer for a venue. But if used to simply plug operating losses without a plan, it might just kick the can down the road.

Overall, traditional loans remain a viable and often cost-effective way to finance venue projects – as long as you prepare through rigorous planning and understand the obligations. Many world-class venues were built or renovated on bank financing. For example, the owners of Paris’s historic La Clef cinema (a collective-run arts venue) negotiated a bank loan to help buy their building in 2024 when faced with a sale – even with community funds raised, they needed support from two banks to reach the €2.35M purchase price. The banks came on board after the group showed broad community backing and a solid revenue plan. The takeaway: if you do your homework and demonstrate commitment, banks can be willing partners in your venue’s future.

Case Study: Leveraging a Line of Credit for Venue Property Management

When discussing venue finance, operators often focus on massive term loans, but flexible capital is equally crucial. Consider this recent case study of a venue property utilizing a line of credit to navigate seasonal cash flow and incremental upgrades. A 1,200-capacity independent music hall in Chicago owned its historic building but faced a common challenge: the property required constant, unpredictable maintenance, and summer festival season always caused a dip in indoor ticket sales. Instead of taking out a rigid term loan, the operators secured a $150,000 revolving business line of credit secured by the venue property.

This financial tool acted as a safety net. In July 2024, when the HVAC system unexpectedly failed right before a sold-out weekend, they drew $40,000 from the credit line to replace the chiller immediately, avoiding canceled shows and refunded tickets. Because they only paid interest on the drawn amount, the carrying cost was minimal. By October, as their busy fall touring season ramped up, the robust cash flow allowed them to pay the balance back down to zero. This real-world example highlights how a line of credit for venues or properties provides the agility needed to handle emergency repairs, bridge off-season gaps, or even fund deposits for major talent without disrupting day-to-day operations.

Looking closely at this case study of a venue property utilizing a line of credit, it becomes clear that liquidity is just as critical as overall profitability. When analyzing any case study on a line of credit for venues or properties, the recurring theme is operational resilience. Having pre-approved access to funds means operators aren’t forced into predatory, high-interest short-term borrowing when a boiler breaks or a major booking requires an immediate deposit. Instead, it transforms a potential crisis into a manageable, temporary balance on the ledger.

Attracting Private Investors & Equity Partners

Identifying Potential Investors for Your Venue

Who would invest in a music or arts venue? It turns out, more types of investors than you might think. The first step is to identify what kind of investor fits your venue. Potential sources of private investment include:

– High-Net-Worth Individuals (Angels): These could be local entrepreneurs, real estate developers, or simply music-loving millionaires in your region. Some wealthy individuals take pride in supporting the local cultural scene and might invest for a mix of modest returns and the social/vanity benefit of owning a piece of a cool venue. For example, a tech entrepreneur in your city who’s a regular concert-goer might be interested in backing your venue’s expansion rather than opening their own restaurant. It never hurts to network at business events or let it be known in the community that you seek investors.

– Artists and Industry Figures: Successful musicians or music executives sometimes invest in venues, either out of passion or strategic interest. In the UK, artists like Ed Sheeran and Frank Turner have even invested in funds to save grassroots venues through community ownership. If your venue has a strong brand or history, a famous artist who has affinity for it might be willing to help (occasionally artists have stepped up to save venues where they got their start). Similarly, independent promoters or agents could invest to have a stake in a regularly gigging venue – essentially vertically integrating their business.

– Strategic Partners (Promoters & Music Companies): Consider partnerships with promotion companies or event producers. A regional promoter might invest capital in your venue in exchange for an ownership share or a long-term booking agreement. This can be mutually beneficial – you get funding and guaranteed shows, they get a home base venue. In fact, many indie venues are partly owned by promotion companies or booking agencies. Be cautious: partnering with a big promoter (like Live Nation or AEG) brings resources but you may lose some independence in booking. Still, mid-tier promoters often look for reliable venues to invest in. Collaboration can be invaluable for concert venues – external promoters bring not just money but expertise, creating win-win venue-promoter partnerships.

– Existing Customers or Community Members: Don’t overlook your own fan base or local community of venue supporters. While these folks might participate via crowdfunding (discussed later), sometimes a loyal patron or local business leader might step up as an anchor investor. For instance, the owner of a nearby brewery or the president of a local music society could have interest in seeing your venue thrive, and capital to invest. These “community angels” often care about the mission as much as the profit.

– Private Equity or Investment Funds: Purely financial investors (like private equity firms) typically focus on larger, highly profitable venues or chains, not single small venues – unless you have a plan to scale up (e.g. open multiple locations or franchise a concept). There are some niche investment funds for hospitality and entertainment properties. If your venue is large (say an arena or major theater) or you plan aggressive expansion, you might attract this type of investor. But for most venues, individual or strategic investors are more likely.

The key is to network extensively: make it known through industry contacts, local business groups, and arts networks that you are open to investment or partnerships. You might quietly circulate a prospectus or reach out to people who have shown past interest in local arts. Venues that have successfully found investors often did so through personal connections or community leadership circles rather than cold calls. So tap your board (if you have one), city officials, music industry colleagues, and anyone who might introduce you to potential backers. And remember, investors can come from anywhere – one independent theater in Australia found a tourism-sector investor from Asia who wanted a foothold in the market; another small venue in Toronto got investment from a group of doctors who loved jazz and wanted to keep the local jazz club alive. Keep an open mind and cast a wide net.

Crafting Your Pitch: Value, Vision, and Viability

Once you have a potential investor’s ear, how do you convince them to invest in your venue? It’s all about presenting value, vision, and viability. In practice, that means blending the hard numbers with the heart and soul of your venue:

– Demonstrate the Business Opportunity: Investors will ask, “What’s in it for me?” Be prepared with a clear explanation of how they could get a return. This doesn’t necessarily mean huge profits (few music venues are cash cows), but perhaps steady annual returns or eventual resale value. Lay out revenue streams (tickets, bar, rentals, sponsorships) and how the infusion of capital will boost those revenues. For example, “With $200k to build a second floor bar, we expect bar sales to increase 50%, generating an additional $100k/year, of which an investor could receive a proportional share.” Show realistic ROI scenarios – even if it’s, say, 8-10% annual return, many investors will find that reasonable for a local business investment. If you’re offering equity, also discuss the long-term vision (e.g. growth or the possibility of selling the venue company in 5-10 years or buying the property for appreciation). If offering a revenue-share or debt investment, outline the payback schedule. Hard data and credible financial forecasts are a must (again, your budgeting homework comes into play).

– Emphasize Your Venue’s Unique Strengths: Unlike a startup selling a new gadget, a venue has intangible assets – community presence, cultural value, brand legacy. Make sure your pitch highlights what makes your venue special and how that translates to a sustainable enterprise. For example, your historic theater might have a loyal patron base and name recognition that ensure a baseline attendance; your nightclub might enjoy a rare 2am license in a city with few late-night venues (a competitive advantage); or perhaps your venue’s programming niche (e.g. Latin music, avant-garde art) cornered a market. Experienced venue operators know to sell their track record – how many shows you host annually, average attendance, notable sold-out events, strong relationships with promoters/artists – all of which reduce the risk for an investor. Essentially, convince them that “This venue is here to stay, and with your help it can flourish – here’s proof.”

– Share Your Vision (and Passion): Investors can get money market returns anywhere; part of why they invest in a venue is the story. Paint a picture of the future: “We want to transform this venue into the premier mid-size concert hall in our region, with state-of-the-art sound and an attached music academy – becoming a community hub and drawing bigger acts. Here’s how we’ll get there…” Show enthusiasm and commitment. Many investors are drawn by the idea of “saving” or “elevating” a beloved venue. If your mission aligns with theirs – say, keeping live indie music thriving in your city – make that emotional appeal. However, balance passion with pragmatism. Avoid overly rosy projections or glossing over challenges; you’ll earn trust by demonstrating awareness of risks and having mitigation plans. For example, acknowledge the competition or past financial struggles, then explain what you’re changing (better marketing, new partnerships, etc.). Transparency goes a long way in convincing people you’re a trustworthy steward for their money.

– Highlight Community Support and Stakeholder Buy-In: If you already have some funding committed (even a grant or your own money), mention it. If local authorities or industry figures support your project (letters of support, or a known artist backing you), leverage that social proof. Investors feel more comfortable joining when they see others on board. For instance, “We’ve already raised $50k from community donations and the city has offered a $25k matching grant – with your investment, we can complete the funding.” Showing that your audience or community is excited – maybe via a successful crowdfunding presale or petitions – can also tip the scales. People invest in momentum, so build that sense that “this will happen, you don’t want to miss out on being part of it.”

When crafting your pitch, it may help to literally create a pitch deck (a slide presentation) and a short executive summary document. Treat it as you would pitching a startup business. Include market demographics (city population, tourism data if relevant), comparables (are there similar venues in other cities doing well?), and clear financials. Keep it concise and focused – hit the main points an investor cares about: How much money, what for, what do they get, how will the venue not fail, and why this is a worthwhile project. Rehearse your presentation and be ready for tough questions (because they will ask!). If financial analysis isn’t your strong suit, consider bringing on a financial advisor or at least having an accountant review your figures before you present them – credibility is everything.

Finally, tailor your pitch to the investor’s perspective. If it’s a culturally-minded investor, stress the community impact and legacy; if it’s a pure businessperson, focus on numbers and risk management. And listen to their responses – understanding an investor’s concerns or goals will help you refine your offer (for example, some may prefer a quicker return via revenue sharing, while others might be happy owning equity for the long haul).

Structuring the Partnership: Equity, Profit-Sharing, or Debt

When an investor is interested, the next step is deciding what form their investment will take. This defines your partnership and has big implications for control and future finances. Common structures include:

– Equity Investment (Ownership Share): The investor buys a percentage of your venue business (or the holding company that owns the venue). In return for their capital, they become a co-owner, sharing in profits (and losses) proportionally. Equity can be minority (you sell, say, 20% and keep 80% control) or majority (over 50%, meaning they have controlling stake – generally not advisable unless you’re comfortable relinquishing control). Equity is patient capital – the investor’s return comes from future profits or a future sale of the business; there’s no guaranteed payout. This can be good for cash flow (no monthly payments), but it dilutes your ownership and decision-making. Be very clear about roles: will the investor be hands-off, or do they expect a say in operations? Pro tip: If doing an equity deal, use a shareholders’ agreement to spell out who has voting rights on what decisions, and consider clauses like right of first refusal (if they try to sell their share, you get first chance to buy it back) to maintain control long-term.

– Revenue-Sharing or Profit-Sharing Deal: Here the investor’s money is treated not as ownership but as an investment that will be paid back from a certain portion of revenue or profit over time. For example, an investor puts in $100,000 with an agreement that they receive 10% of the venue’s gross revenues each quarter until they’ve recouped $150,000 (their principal plus 50% return). Or it might be framed as, say, 20% of net profits for X years. This is essentially a revenue-based financing model. It’s attractive to some investors because they start seeing returns quickly (as you earn, they earn). For venue operators, the upside is you don’t give up ownership, and if business is slow, payments adjust (you’re not paying a fixed amount regardless of income). The downside: if business is strong, you might end up paying a lot more back (but that’s okay if the pie grew). These deals need crystal-clear formulas and caps – many use a cap (like in the example, payments stop once 1.5x the investment is paid). They also require robust bookkeeping (investor will want to verify the revenue numbers). But many independent venues have done informal profit-share deals with backers. It aligns incentives in that the investor succeeds only when the venue does. Just be cautious to structure a percentage that leaves you enough operating cash; don’t promise such a big slice that you starve your own budget.

– Private Loan (Debt) or Convertible Debt: Sometimes an investor might actually prefer to lend the money to the venue at an agreed interest rate, rather than take equity. This is basically a private loan (could be promissory note, etc.). For example, a local benefactor lends you $200k at 5% annual interest, to be repaid over 10 years. This can be simpler – you treat it like any other loan (often slightly more flexible terms since it’s not a bank). However, investors may do this only if they trust you greatly, since they are taking similar risk as equity but with capped return (the interest). Convertible debt is a hybrid: it starts as a loan, but the investor can convert it to equity under certain conditions (say, if not repaid in 5 years, or if the venue’s value increases, etc.). This is more common in startup finance but could be used if an investor likes the idea of equity but also wants some protection – they lend you money and will convert to ownership if you can’t pay it back. For you, that means if things go well you simply pay a loan; if things go poorly, you might not pay the money back but they end up owning part of your venue. Again, get legal counsel to navigate these structures.

– Joint Venture or Project Partnership: If the financing is for a specific expansion or new program (like opening a second location, building a rooftop lounge, etc.), you might set up a joint venture entity just for that project. The investor puts money into that entity and you both share its returns, without them owning your main business. For example, you and an investor create “XYZ Venue Events LLC” to which the investor contributes capital to produce a new festival series at your venue, and you split profits from those events, but the investor doesn’t own your venue itself. This can ring-fence the partnership to one aspect. However, it adds complexity to manage separate entities. Still, it’s a way to partner on revenue-generating initiatives without selling the farm.

No matter the structure, use experienced entertainment attorneys to draft the agreements. There are many details to cover: what exactly the investor gets (equity %, profit %, etc.), when and how they get paid, their role (advisory? board seat?), what happens if either party wants out, dispute resolution, etc. Don’t just download a generic contract – work with someone who knows venue or small business deals. Also, think long-term. Many venues have gone wrong by taking what seemed like friendly investments, only to face conflicts later over creative direction or money, similar to challenges in sourcing funding and investment for festivals. Clear agreements and aligning values up front would mitigate this. (We’ll talk more about safeguarding your mission in a later section.)

One more thing: be realistic about valuation. If selling equity, you and the investor must agree what the whole venue business is worth to decide how much equity their money buys. Venue businesses don’t follow Silicon Valley multiples; often it’s based on a multiple of annual EBITDA or simply negotiation. If your venue nets $50k a year profit, an investor isn’t going to value you at $5 million. Many venue deals happen around 3–5x annual profit or even just 1x revenue for small venues – but every case differs. The more unique and growth potential your venue has, the better your valuation argument. Just be prepared that you might need to part with a significant slice of ownership to raise substantial money, which is why some operators prefer debt or other means if they feel valuations are too low. It’s a trade-off: maintain control vs. obtain capital. There’s no universal right answer – it depends on your goals, the investor’s stance, and how much you need the money.

Success Story: When a Private Partnership Saved a Venue

To illustrate how investor partnerships can work, let’s look at a success story. Case Study: The Phoenix Concert Hall (fictional name for a real scenario) – a 600-capacity independent venue in Germany – was on the brink of closure in 2021. The owners had exhausted personal funds during the pandemic and needed €250,000 to refurbish and rebrand the aging club to bring back crowds. Traditional loans weren’t an option (they were already in debt from lockdown). Instead, they found an unlikely investor: the founder of a local tech company who happened to be a long-time fan of the venue.

This angel investor offered the needed €250k in exchange for a 35% equity stake in the business. Both parties agreed they wanted the venue to remain true to its spirit, so they wrote into the agreement that the existing owners would retain all day-to-day control and that any sale of the venue or major change (like switching music format) required mutual consent. The investor wasn’t in it for quick profit – he loved live music and saw this as an impact investment with hopefully modest returns. Over 2022–2025, that infusion of capital allowed the venue to make critical improvements (a new sound system, revamped interior, and marketing campaign) that dramatically boosted attendance. By 2025, revenue had doubled compared to 2019, and the venue became profitable again. The investor’s share of annual profits ended up around €30k by 2025 (a roughly 12% return on his investment – not bad for a passion project), and the venue was saved from the brink.

This partnership worked because the investor’s values aligned with the venue’s mission – he explicitly wanted to keep the indie music scene alive. There was good chemistry and clear communication. The owners regularly update the investor on the club’s performance, and he occasionally uses his business expertise to advise on marketing. They even gave him a small “VIP investor booth” in the club as a token of appreciation (and a fun perk he enjoys with friends). Crucially, the legal agreement had an exit clause: neither party can force a sale of the whole venue before 5 years, and after that any party can be bought out if an independent valuation is agreed upon. This ensures down the line, if either wants to part ways, there’s a process.

Not all investor stories are so rosy. Pitfall Example: A different venue, a community theater in Canada, took on an investor who put in money but later demanded repayment far sooner than agreed because his own financial situation changed. The venue hadn’t yet stabilized and couldn’t buy him out, leading to legal disputes. The lesson: include provisions for if an investor wants out early (right of first refusal for you to find a replacement investor, or a predefined buyout formula) and try to vet the investor’s stability and expectations. Also, maintain an open dialogue; surprises are often what cause panics and conflicts.

In summary, private investors can catalyze a venue’s success, bring new ideas, and share the financial burden. Many iconic venues have survived thanks to a well-structured partnership – from small clubs saved by local benefactors to major theaters that brought on private equity for big renovations. The keys are to find the right partner, align on goals, and document everything to avoid misunderstandings. If you do that, investor money can indeed fuel your venue’s future without derailing its spirit.

Creative Financing: Sponsorships, Revenue-Sharing & Alternative Deals

Not every funding solution comes from a bank or equity investor. Some venue operators have leveraged creative financing models that tap into future revenue or partner resources in clever ways. These alternatives can be more flexible or mission-friendly than traditional loans, though they come with their own trade-offs. Let’s explore a few:

Revenue-Based Financing: Pay as You Earn

Imagine getting funding now and paying it back only as your venue generates revenue, rather than a fixed monthly sum. That’s the idea behind revenue-based financing. In this model, you receive capital upfront (from an investor or specialized financing company) and agree to pay back a percentage of your monthly or quarterly revenue until a certain total payback is reached. It’s like the profit-sharing investor deal we discussed, but often structured with a firm payback cap. For instance, you receive $100,000 now, and each month you pay 5% of your gross revenue back until you’ve paid $120,000 in total (which might take a few years, depending on sales). If business is slow, your payments shrink; if business is booming, you pay it off faster.

This can be attractive to venues with volatile income or strong seasonal swings. During slow months, you’re not crushed by a fixed loan payment. And it aligns the funder’s interest with yours – they only get paid when you do well. There are now fintech companies and funds offering revenue-based financing to small businesses, including restaurants and venues, typically in the five to six-figure range. They usually charge a higher effective cost than a bank loan (that $100k for $120k payback is effectively a 20% premium, which might equate to an APR in the low teens depending on speed of repayment – still often less than credit cards).

When considering these deals, read the terms carefully. Key questions: Does the percentage come off gross revenue or net (gross is more common)? What’s the maximum time it can go (is there a time after which you still owe a balance, or is it purely until cap is reached)? Are there any personal guarantees (usually not, as the revenue itself is the collateral)? Also, ensure the percentage is reasonable – giving up 5-10% of gross revenue can be fine, but much higher and you may starve your operations. It’s wise to run worst-case scenarios: if your revenue is 30% lower than expected, can you still cover expenses after giving them their cut? The flexibility is nice, but it’s not “free money” – you are essentially pre-selling a chunk of future earnings.

Real-world usage: A mid-size venue in Texas used a revenue-based advance to fund a new LED wall installation. They got a $80,000 advance from a specialty lender, agreeing to pay 8% of their monthly ticketing and bar revenue until $100,000 was repaid. It took them about 30 months to hit that target (business rebounded strongly post-COVID, so sometimes they paid $4k in a month, sometimes only $2k in slower months). In the end, it cost a bit more than a bank loan might have, but they didn’t have to worry about fixed payments during several unpredictably slow months. They also avoided putting up collateral. They felt it was a fair trade to get the upgrade done when banks weren’t willing to lend at the time.

Increasingly, even ticketing platforms are offering flexible financing tied to event revenue. For example, Ticket Fairy’s event ticketing platform offers an advance funding program that can provide qualified promoters and venues anywhere from $10,000 to $3M upfront to cover production or venue upgrade costs, with the advance recouped from ticket sales. These kinds of industry-specific solutions integrate financing with your cash flow – essentially using your future ticket revenue as collateral. (Unlike shady ticket resale loan schemes, Ticket Fairy’s approach doesn’t involve surge pricing or predatory terms – it’s designed to support the venue’s growth.) The takeaway is: explore industry fintech options; you might find a revenue-based deal that suits your needs better than a rigid bank loan.

Vendor Partnerships & Barter Financing

Another creative route is to leverage partners or vendors for financing or in-kind support. This can take many forms:

– Equipment Financing/Leasing: If you need expensive gear (sound boards, lighting rigs, video screens), many equipment vendors or leasing companies will allow you to pay over time – basically a loan but secured by the equipment itself. Often these are structured so that the gear effectively “pays for itself” as you use it for shows. Some companies even do lease-to-own deals. While this is common (not that creative), what’s interesting is negotiating directly with a vendor for a special arrangement. For instance, a sound company might install a top-of-line PA in your venue at a discount or no upfront cost if you agree to exclusively use and showcase their brand and maybe share a tiny cut of event revenue with them. They get marketing exposure and possibly a slice of ticket or bar sales until the system is paid off. It’s like a sponsorship (discussed next) combined with financing. If you have a good relationship with an equipment provider, it’s worth asking – sometimes they have programs for venues.

– Sponsor or Brand-Funded Upgrades: We typically think of sponsors as paying for advertising at a venue, but they can also fund infrastructure. For example, a brewery or beverage distributor might bankroll the construction of a new bar or VIP lounge in your venue in exchange for a multi-year exclusive beverage contract and branding rights on that space. You get a new facility; they recoup via product sales and exposure. A famous example is London’s 100 Club, which was saved from closure when Converse (the shoe brand) stepped in with a sponsorship deal to save the 100 Club. Converse got branding inside the venue and goodwill for preserving a music landmark. In arena-scale venues, naming rights deals are essentially this model – a brand pays a large sum upfront (or annually) that often helps fund venue construction or renovation, and in return the venue carries the brand’s name (e.g. “CFG Bank Arena” after a $250M renovation in Baltimore, or “Crypto.com Arena” in LA). At a smaller scale, you might name your new stage after a sponsor who financed its build, or have “The [Sponsor Name] Green Room” if they helped refurbish backstage. The key is to match with sponsors that see clear value in associating with your audience – and to ensure the funds they provide are earmarked for the venue improvements promised.

– Promoter Co-Promotes and Guarantees: Earlier we noted promoters as potential investors; even short of an ownership stake, you can structure deals where a promoter helps finance certain shows or series at your venue to share risk and reward. In a “co-promote” agreement, a promoter might front some of the money for an artist guarantee or production costs, in exchange for a cut of the show’s profits. This frees up your capital for other needs (effectively the promoter is financing that event). While this is more an operational financing rather than capital investment in the venue, it can indirectly support your finances by reducing out-of-pocket costs. Some venues negotiate season-long deals: e.g. a promoter commits to bringing X number of concerts and covers upfront costs for those, ensuring the venue a baseline of content without spending its own cash on booking. This kind of partnership was crucial during the shaky reopening period post-pandemic – venues that partnered with promoters for risk-sharing managed to host shows without betting the bank on each booking. It’s a win-win deal structure for venue-promoter partnerships that fills your calendar while controlling financial risk.

– Barter and In-Kind Contributions: Think outside the box of cash. Perhaps a local construction firm is willing to renovate your venue at below market cost during their slow season, if you give them free event space for their corporate parties for a couple years. Or a lighting tech company provides gear in-kind for your upgrade if you prominently credit them and allow potential clients to tour your venue as a showcase. These indirect financings reduce the money you need to raise. One real example: a theater in Minneapolis struck a deal with a seating manufacturer – the company installed new seats (value over $100k) at minimal charge, and in return the venue became a showpiece the manufacturer uses to bring other clients to see their seats in a real venue environment. Essentially, the company treated it as marketing expense. The theater could never have afforded those seats otherwise.

The common thread in all these is trading future value or exposure for present investment. It requires finding partners whose business goals align with your needs. To pursue such deals, get creative in your outreach: if you need a new HVAC, maybe approach an HVAC company about sponsorship; if your stage is crumbling, maybe a local carpentry business could become a sponsor in exchange for rebuilding it at cost. You’ll need to put together a mini-pitch for these partners just like you would for a cash investor: what will they get out of it? Use data about your audience demographics, foot traffic, media coverage, etc. (For guidance on articulating value to sponsors, see our detailed playbook on attracting and growing venue sponsorships – it explains how venues can secure brand partnerships that offset costs and boost income by highlighting their unique audience and assets.) The more you can show the tangible benefit to the partner, the more likely they’ll contribute resources that effectively finance your upgrades.

Of course, be careful with promises: if you give a sponsor too much control or visibility, you might alienate your crowd (nobody likes a venue plastered in ads, and you don’t want to turn off fans by “selling out” excessively). Choose partners that enhance the venue experience rather than detract from it – e.g. a quality beer brand building you a cool bar is a plus; a random corporation slapping their logo everywhere for a buck is not worth it in the long run. Also, structure the duration of such deals clearly (most sponsorship or vendor deals should have an end date or performance clauses). You don’t want to be tied to an underpaying sponsor forever, especially as your venue grows in value. The great thing about creative partnerships is they can significantly reduce the cash you need to raise, and they build a network of stakeholders invested in your success. The flip side is complexity – you may have to manage ongoing obligations (free tickets for sponsors, revenue sharing calculations, etc.). Keep the accounting transparent and honor your deals, and these partnerships will remain fruitful sources of support.

Event Financing: Should I Take a Loan for a Big Event?

A frequent question among ambitious promoters and venue operators is: “Should I take a loan for a big event?” While securing capital for long-term property improvements is standard practice, borrowing heavily to fund a single, high-risk show requires extreme caution. Event financing is inherently volatile; a sudden weather cancellation, an artist dropout, or poor ticket sales can leave you with a massive debt and no asset to show for it. If you are considering taking on debt for a specific festival or blockbuster concert, it is generally safer to explore revenue-based advances (like ticketing platform funding) or co-promotion deals where risk is shared, rather than putting your venue’s core assets on the line for a one-off gamble.

If you do decide that borrowing is the only way to secure a marquee booking, approach this specific type of event financing with strict guardrails. Venue finance experts recommend ring-fencing the event’s budget from your core operational funds. Consider short-term bridge loans or specialized promoter advances that are tied directly to ticketing milestones rather than traditional bank debt. By structuring the capital this way, you protect your venue property from being liquidated if the festival or mega-concert underperforms. Always run a break-even analysis factoring in the cost of capital before signing any term sheet.

Below is a quick comparison of various financing models – how they work, their benefits and drawbacks, and examples – to help visualize where these creative options fit in:

| Financing Model | Typical Use Case & Method | Benefits | Drawbacks / Risks | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bank Loan (Term Loan or Mortgage) | Major renovations, expansion, property purchase. Borrow lump sum, repay with interest over 5–20 years (fixed monthly payments). | – Predictable payments and timeline. – No loss of ownership or control. – Can be low interest if credit is good. |

– Adds fixed debt cost regardless of business performance. – Requires collateral or guarantees; risk of asset loss on default. – Tougher approval if venue finances are weak. |

A theater takes a $500k loan over 10 years to upgrade its sound and lighting systems, using the building as collateral. Monthly payment ~$5.5k. |

| Private Investor (Equity) | Opening new venue or major capital injection. Investor buys stake (e.g. 20-40% ownership) in exchange for funding. Shares profits going forward. | – Large capital infusion with no immediate repayments. – Investor may bring expertise and industry connections. – Spread risk with a partner. |

– Permanent share of profits given up; potential loss of control if a big stake. – Possible disagreements over business decisions or vision. – Equity can be complex to value; exiting partnership can be tricky. |

A local entrepreneur invests $1M for a 30% equity stake to reopen a historic venue. The investor gets 30% of annual profits and a say in major decisions. |

| Private Investor (Revenue/Profit Share) | Venue needs funding for improvements but owner wants to retain full ownership. Investor puts in cash for a defined share of revenue or profit until a target is met (or for a set term). | – No equity surrendered if structured as pure revenue share. – Payments flex with performance – easier to handle in slow periods. – Investor incentive aligned with venue success. |

– If business grows quickly, investor could earn more than a loan interest would have cost. – Requires diligent tracking and transparent reporting of revenue. – Terms can be complex; need clear cap or end date to avoid perpetual payouts. |

An investor provides $100k to upgrade the venue’s patio in exchange for 15% of quarterly net profits until $180k total is paid back (approx. 5 years if projections hold). |

| Equity Crowdfunding / Community Shares | “Save the venue” campaign or expansion funded by a large number of small investors (fans, community). Investors collectively own a stake or receive revenue share. Often done via online platforms. | – Engages your fan base; turns supporters into owners/ambassadors. – Can be marketed as a community cause – good PR and loyalty boost. – No large single debt obligation; terms can be designed favorably (e.g. non-voting shares). |

– Very time and effort intensive to market and manage the campaign. – May need hundreds of investors to reach goal – lots of stakeholder management. – Regulatory requirements (equity raises must comply with securities laws, though many countries have crowdfunding exemptions up to certain amounts). – If offering equity, future profits are shared and many shareholders involved. |

Fans purchase community shares to raise $250k to keep an indie club open. 500 fans invest $500 each for a collective 40% non-voting equity; a community-elected board represents their interests while founders retain control. |

| Brand Sponsorship / Naming Rights | Specific venue upgrades or operating support funded by a corporate sponsor in exchange for branding, exclusivity or naming rights. Often multiyear deals. | – Instant capital infusion (or valuable in-kind support) without debt or equity loss. – Brand’s marketing might amplify venue’s profile. – Can offset operational costs (e.g. a beer sponsor provides annual cash plus product). |

– Sponsor may demand significant branding or influence that could alienate some patrons (watch for “selling out” perception). – Typically time-limited; when deal ends you might need to find a new sponsor or lose that income. – If sponsor faces PR issues, could indirectly affect venue’s image. |

A brewery funds $100k towards a new outdoor stage and bar build-out. In return, they get pouring exclusivity at the venue and the area is named after the brand for 5 years. The sponsor’s investment covers construction costs the venue couldn’t afford upfront. |

| Vendor Financing / Trade-Outs | Venue gets equipment or services now and pays later or over time, often by partnering with the vendor. Could involve lease-to-own, or free/discounted equipment in exchange for something (marketing, revenue share). | – Low or no upfront cost for crucial improvements. – Partner’s interests aligned (they want you to succeed to showcase their product or recoup via revenue). – Less paperwork than bank loans in some cases. |

– If revenue share or deferred payment, can bite into future cash flow. – May be obligated to stick with a vendor/brand even if you find better options later (lock-in risk). – Need to deliver on any promised exposure or contract terms to keep relationship positive. |

A sound company installs a new $75k PA system at no upfront cost. The venue agrees to pay 8% of ticket revenues to the vendor for 3 years (or until $90k is paid). The vendor also gets to showcase the system to potential buyers at the venue. |

Each of these models can be the right solution under the right circumstances. In fact, many venues use a combination – for instance, a bank loan for building repairs and a sponsor for new furniture, while the owner still retains majority equity but maybe gives a small share to a partner. As a venue operator, it’s your job to mix and match financing tools to fit your unique project and risk tolerance. Next, we’ll discuss tapping the crowd and community, which has become a lifeline for many venues in recent years.

Crowdfunding & Community Investment: Fans as Financial Lifelines

Turning Fans into Investors (Equity Crowdfunding 101)

When traditional avenues falter, who better to turn to than the people who love your venue most – your audience and community? Crowdfunding allows you to raise capital from a large number of supporters, each contributing a small amount, that adds up to a significant total. By 2026, venues have gotten very savvy with crowdfunding, moving beyond simple donation drives to more structured community investment campaigns.

There are two main types of crowdfunding relevant to venues:

– Donation/Reward Crowdfunding: This is the Kickstarter-style approach. Supporters donate or pledge money (often in exchange for rewards like free tickets, merch, their name on a “thank you” wall, etc.). They do not get equity or a share of profits – it’s essentially a fundraising campaign, sometimes framed as “Save our venue” or pre-selling future tickets. Many venues used this model during the COVID shutdowns (e.g. GoFundMe campaigns) successfully. It’s simpler (less legal hassle) but is essentially asking for altruism or selling perks. There’s no financial return for supporters beyond the rewards or goodwill.

– Equity Crowdfunding / Community Shares: Here, supporters actually invest and receive a form of equity or financial instrument that ties their contribution to the venue’s future success. In some cases it’s literal shares in the company (via regulated equity crowdfunding platforms). In other cases, especially in the UK and Europe, it might be a Community Benefit Society model or a cooperative share (where people get membership and possibly dividends or interest, but not traditional stock). This approach treats the crowd as investors – typically small investors putting in maybe $100–$1,000 each – but potentially hundreds or thousands of them. Equity crowdfunding is regulated: for example, in the US, Regulation Crowdfunding allows companies to raise up to $5 million a year from the public with certain disclosures; the UK has well-established equity crowdfunding platforms like Crowdcube and Seedrs that have facilitated venue campaigns; Europe and Australia have their own rules but generally allow these campaigns with caps. It’s critical to use a reputable platform that handles the legal compliance and transaction processing, rather than trying to sell shares under the table (which could violate securities laws).

What do community investors get? Some campaigns offer a straightforward share of ownership – e.g. each $500 share entitles the holder to 0.001% of the venue company and any dividends. Others might structure it as a profit-sharing bond (supporters invest and will get their money back with interest if the venue does well, basically a community loan). Or as membership stakes, where they get voting rights on certain venue matters and maybe perks, but any financial return is limited. The UK’s Music Venue Trust, for example, launched community share offers to buy freeholds of venues, where investors get a small annual return and the social benefit of preserving venues through community ownership.

Equity crowdfunding has opened up a new frontier because it lets you tap into the passion of your fan base as investors, not just donors. Fans-turned-investors can become powerful ambassadors for your venue – they literally have a stake in its success. Plus, raising say $300k from 600 people giving $500 each might be more achievable than finding one or two investors to pony up that amount. However, you have to manage a large number of stakeholders and comply with whatever reporting or communication you promised. Many campaigns communicate via email newsletters or online forums to their army of new mini-shareholders, keeping them updated on the venue’s progress.

Designing a Crowd Investment Campaign (and Making it Succeed)

Running a crowdfunding campaign – especially one where you seek large sums – is a major project in itself. Here are some keys to success:

– Compelling Story and Urgency: Just like pitching an investor, you need to sell the crowd on why the venue needs the money and what for. But with the public, the emotional appeal is even more important. Are you preserving a piece of cultural heritage? Building something the community desperately needs? Fighting off a threat (like redevelopment)? Create a narrative that people want to be a part of. A bit of urgency or a deadline can spur action (e.g. “we need to raise $200k by March to keep our lease, or we may close”). Be genuine – authenticity resonates. The legendary Melbourne venue “The Tote” described its crowdfunding as the last chance to save a beloved music institution from being turned into apartments, which galvanized fans globally to help raise AU$3 million to save The Tote.

– Tangible Goals and Rewards: If donation-based, set attractive rewards at various tiers (and price them such that you still net a lot). For example, at $50 a donor gets their name on a mural, at $100 a free ticket to a reopening party, $500 gets a year-long VIP pass, $1000 gets their own bar stool with their name on it, etc. Be creative and offer experiences money can’t usually buy (meet & greet with a band at the venue, etc.). If equity-based, while you can’t offer “rewards” per se beyond the investment instrument, you can still offer small perks to investors (like all investors get a membership card, or early access to tickets, etc. – just ensure it doesn’t violate any securities rules on offering additional inducements). The more people feel they are joining a special club by investing, the more they’ll chip in.

– Set Realistic Targets (with a Cushion): Decide how much you need versus how much you think you can reasonably raise from your community. Look at your fan base size, social media following, and prior crowdfunding outcomes in your area. It’s often wise to set a minimum goal to at least hit a critical amount, but also have a stretch goal. Some platforms allow flexible funding (you keep what you raise even if short of goal) while others are all-or-nothing. All-or-nothing can motivate urgency but be careful to not set it so high that you risk getting nothing. Also factor in fees (crowdfunding platforms take ~5-8%) and costs of campaign (video production, marketing, etc.). Aim to exceed your minimum goal because there are always unplanned expenses in venue projects.

– Marketing the Campaign: Think of a crowdfunding campaign like a concert or festival – you must promote the heck out of it. Launch with a bang (press releases, local news coverage, an event if possible). Leverage all channels: email lists, social media, press, artists who love your venue (ask bands to share the campaign link or even do a short video calling fans to support), community organizations, and local businesses. Regularly update progress and celebrate milestones (“We hit 50%, keep it going!”). People are more likely to jump in when they see momentum and community buzz. Many successful venue crowdfunds have a mid-campaign event – maybe a benefit show or live stream – to spike interest. Also, personal outreach matters: get your staff, promoters, and loyal patrons involved in spreading the word. It can feel like a political campaign – because you are rallying a crowd to your cause.

– Transparency and Trust: Especially for investment-based campaigns, address potential supporters’ questions openly. Why this amount? How will funds be used exactly? What’s the plan if you hit or don’t hit the goal? Who’s managing the funds and project? The more you show you have a solid plan (with maybe sketches of the renovation, quotes from contractors, or a timeline for reopening), the more confidence people will have to invest. Also be clear on investor perks/returns: if you promise a dividend or interest, make sure it’s realistic and legally compliant. Many community investors are okay with a modest return, but they at least want to know the structure. And if it’s a donation campaign, reassure how their money secures the venue’s future (e.g. “This will cover rent for the next year and install a new sprinkler system so we can continue operations safely.”)

– Anchor Investors and Match Funding: A tactic to build credibility is securing some larger commitments behind the scenes that you announce at launch. For example, a local business or a city development fund might agree to contribute a chunk (say $50k) if the crowd raises the rest. Announcing such matching funds or initial seed investments signals to the public that major stakeholders believe in the project, which encourages smaller investors to join. During the UK’s Own Our Venues campaign, having famous artists and even institutional grants in the mix (like Arts Council England’s £500k support) gave social proof that the mission was sound, as seen in the Own Our Venues initiative. Even on a smaller scale, “lead gifts” help – maybe a couple of superfans pledge $5k each; you tout that as “already 10% funded by first supporters!” which motivates others.

One crucial aspect: if you’re doing equity or shared ownership, plan the governance. Do the community investors get any say (board seats, voting on certain issues at an annual meeting)? Or is it purely a financial arrangement? Many venue campaigns choose to form a community trust or cooperative that holds the asset (like the building) while an operator runs the venue. For example, the Music Venue Trust’s initiative uses a Community Benefit Society model to buy venue properties and then lease them affordably to venue operators. The community investors invest in the society (not the venue directly) and get a small return and the knowledge that their money is preserving the venue. In other cases, venues have just added potentially hundreds of direct shareholders – which can be messy to manage unless using nominee structures (some crowdfunding platforms pool all investors under one nominee entity to appear as one shareholder for simplicity). Decide what makes sense for you and communicate it. You might say “all investors become members of the Friends of XYZ Venue nonprofit, which will advise on venue programming” if you want involvement, or conversely “investors are passive and the existing management continues making all decisions” if you need that clarity.

Success and failure stories abound. On the success side, take “The Tote” in Melbourne: facing sale and likely closure, the community, spearheaded by loyal music promoters, launched a campaign that raised over AU$3 million from about 12,000 fans in 2023. This money, combined with additional funds from the new owner-managers, secured the venue’s purchase, and it is now slated to be held in a trust for future generations. This shows the power of sheer fan devotion – people will invest to save a cultural icon. In the UK, Music Venue Trust’s ongoing Own Our Venues project raised over £1.8M to secure grassroots music venues toward purchasing grassroots venue properties, showing how industry and community can come together (with contributions ranging from small fan investments to big names like Ed Sheeran chipping in). On the other hand, there have been campaigns that fell short. A common pitfall is overestimating the crowd – not every venue has a large enough fan base willing to pay. Some venues tried during COVID to raise huge sums and only got a fraction, sometimes because their outreach didn’t break out of their immediate circle. Other failures involve poor communication or misuse of funds (if supporters feel their money wasn’t used as promised, trust is broken).

In summary, crowd-based financing can be incredible for not just raising money but cementing your venue’s place in people’s hearts. It turns a business transaction into a community project. But it’s hard work – essentially a full-fledged campaign that requires as much savvy in marketing and PR as it does financial finesse. Done right, you not only get funding, but you also gain an army of advocates. As one venue operator put it, “Our crowdfunders are now our family – they’re our loudest promoters, they bring friends to shows, they even volunteer to help paint the place. We got way more than money; we solidified our future customer base.” That kind of engagement is priceless and can pay dividends for years to come. Just go in with eyes open: consult legal experts for equity campaigns, commit the time to run the campaign properly, and be prepared to deliver on your promises to the crowd.

Successes, Pitfalls, and Lessons from Community-Funded Venues

Let’s highlight a few notable examples from around the world where community financing played a definitive role, and what we can learn from them:

- Melbourne’s The Tote – Saved by Community Shares: We discussed this above – an iconic rock club put up for sale in 2023, spurring a massive community investment drive. The campaign hit its AU$3M goal thanks to enormous grassroots energy. However, the road had bumps: when the initial crowdfunding target was reached, the existing owners unexpectedly said the initial offer wasn’t enough, causing public backlash. Ultimately, the new buyers (a pair of local music promoters leading the campaign) negotiated a deal to save The Tote from closing by combining the crowdfunded money with their own funds and a bank loan. Lesson: Even after a successful raise, negotiations can get tough – have contingency plans and don’t declare victory until contracts are signed. From a supporter management view, The Tote’s team had to quickly address confusion and frustration when the sale wasn’t immediately secured despite reaching the goal. They did so by communicating transparently and doubling down on their commitment, which kept the community on board until the purchase was finalized. Now The Tote is slated to be placed in a community trust, meaning it will be protected for future generations as a music venue. It’s a triumphant outcome showcasing how die-hard fans can literally become owners to keep a venue alive.

- UK Grassroots Venues – Own Our Venues Campaign: The Music Venue Trust (MVT) in the UK launched the “Own Our Venues” initiative in 2022, which is essentially a nationwide crowdfunding effort to buy the freehold (property) of small venues and lease them back affordably under protected status of benevolent ownership. By late 2025, in its first phase, it raised over £1.5M from 1,300+ investors. Additionally, music industry companies and famous artists invested (Ed Sheeran, Sony Music, etc.). This campaign’s success (and continuing momentum) highlights a big lesson: collective action through a central organization can unlock support that an individual venue might not get. Not every tiny venue could find Ed Sheeran to invest, but by banding together under MVT, the movement gained star power. It also taught us about structuring community investments: MVT used a Community Benefit Society model, meaning investors get community shares with a target modest return (~3% annually) and the satisfaction of preserving venues, rather than moonshot profits. Lesson: When pitching community investment, aligning it as a social-good investment (with reasonable returns) can attract both sentimental fans and more traditional investors. Transparency has been key too – MVT regularly updates investors on venue purchases and has clear governance for how venues are selected and managed. This fosters trust and sustained support.

- Paris’s La Clef Cinema – Cooperative Purchase: Crossing into cinema (a venue nonetheless), the story of La Clef in Paris is instructive. A collective of film-lovers occupied the defunct art cinema and fought for years to buy it from a property developer. They combined crowdfunding, public fundraising events, and crucially secured bank loans to finally purchase the venue in 2024. The owner agreed to a lower price (€2.35M down from €2.9M) given the community pressure and needed renovations. It took support from two ethical banks (Crédit Coopératif and La Nef), plus a major donation and sponsorship, to close the deal. Lesson: Crowdfunding alone wasn’t enough – they had to smartly mix sources (sound familiar?). The community group’s persistence and ability to get a bank on board shows that a passionate community can even sway financial institutions when the cause is sound. But it also exemplifies how slow and challenging the process can be (several years in this case). Another takeaway: they formed a cooperative to run La Clef, illustrating that a community-owned venue can be structured democratically, but one must be prepared for the complexity of consensus decision-making once the dust settles.

- Local Pub and Venue Buyouts: In smaller towns, there have been cases of local residents pooling money to buy their pub or music venue when the owner retires or plans to sell. These often rely on community bonds or shares. For example, villagers in Somerset, England saved their centuries-old pub this way in 2022, and that pub doubles as a music venue on weekends. While these might involve smaller sums (tens or hundreds of thousands), the principle is the same. Lesson: even if your venue isn’t famous globally, you may have enough supporters locally to mount a community buyout if you become threatened. It helps if the venue has been around long enough to be deemed “an institution”. Engaging local council or government support can bolster these efforts – sometimes they pitch in funds or at least technical assistance if they see public will.

- When Crowdfunding Falls Short: It’s also educational to see when it doesn’t work. A hypothetical example drawn from several real ones: a mid-sized venue in a big city attempted to crowdfund $500k for renovations but only raised $50k. Why? Factors included a lack of wide community recognition (it was relatively new and niche), insufficient marketing (few press stories, mostly just the venue’s own social media, which didn’t reach new audiences), and donors not understanding where the money was going (vague goals). That venue had to scrap its expansion and later quietly brought on a private investor anyway. Lesson: Crowdfunding isn’t magic – it requires either a large passionate following or extraordinary outreach efforts (preferably both). If your venue is newer or not immediately emotionally resonant to a lot of people, you might be better off focusing on traditional financing or significantly upping your marketing game to educate people on why they should care and contribute.

To summarize the crowdfunding chapter: community financing can yield incredible results – a saved venue, a bought building, a stronger bond with your patrons. It can also be a rollercoaster of uncertainty, work, and emotions. Plan diligently, inspire your supporters, and have backup strategies. Even if you fall a bit short, partial funds raised can sometimes be leveraged to get other funding (e.g. showing a bank that “we have $50k from the community, can you lend the rest?”). And remember, not every venue will luck out with rockstars and hundreds of investors swooping in – but if you don’t ask, you don’t get. Many venue operators are pleasantly surprised by how much their community will rally when given the opportunity. In 2026, fans expect transparency and a chance to be part of the story – crowdfunding gives them that, and can give you the capital to write your venue’s next chapter.

Combining Funding Sources for Maximum Impact

So far we’ve looked at loans, investors, partnerships, and community funding as separate paths. In reality, many venues use a blend of these financing sources to meet their goals. Think of it like financing a film – rarely does one investor cover the whole budget; instead you assemble a patchwork of funding. For venues, mixing sources can reduce reliance on any one channel and play to each source’s strengths. However, it requires good coordination and planning to ensure the pieces fit together. This section explores how to layer multiple financing methods effectively.

Layered Funding Strategies: Diversify Your Capital Stack

Why combine sources? Often because no single source can (or should) give you everything. For example, maybe you can only qualify for a bank loan up to $200k, but your project is $500k – you might raise the rest via investors or crowdfunding. Or perhaps an investor will give money but you don’t want to give away too much equity – so you take some debt too. Diversifying funding can also spread risk and obligation: a bit of debt (with fixed payments), a bit of equity (no payments, but sharing future upside), maybe some crowdfunding (which might be lower pressure money if from fans), and some sponsor contribution (essentially “free” money in exchange for marketing). By balancing the mix, you avoid overloading on any one thing like debt.

One common combination in 2026 is: Bank Loan + Crowdfunding + Grants/Donations. For instance, a venue might get a bank loan for structural repairs, run a crowdfunding campaign for things the community cares about like a new mural or improved seating, and also apply for any available arts grants or city funds to cover specific items (like soundproofing or accessibility upgrades). Each piece covers a part of the budget. The advantage is if one piece falls short, the project might still proceed scaled to what’s raised. It’s like having multiple lifelines. In an ideal scenario, success in one area fuels others – e.g. a strong crowdfunding start might convince the bank to approve the loan (seeing community support as a validation), or landing a small government grant might impress private investors that your venue has civic backing.