Live events in 2026 are bigger than ever – and so are the challenges of managing union labor on-site. From local stagehand unions in big cities to trade unions for electricians and riggers, venue operators must navigate a maze of rules and expectations. Those rules come with real benefits (skilled, safety-conscious crew) but also added costs and complexity. In an era when many independent venues face razor-thin margins amid rising costs and strategies for overcoming staffing shortages, understanding how to work effectively with unionized staff is more critical than ever. This guide demystifies union labor compliance, budgeting, and crew harmony, helping venue managers keep shows running smoothly without costly disputes.

Understanding the 2026 Union Labor Landscape

Why Unions Still Matter in Live Events

In 2026, labour unions remain a powerful force in the live entertainment industry. Stagehands, technicians, and even some front-of-house staff at larger venues are often union members protected by collective bargaining agreements. These agreements set standards for pay, working hours, safety practices, and more. The resurgence of live events post-pandemic has coincided with a wave of labour activism across many industries – and live entertainment is no exception. From concert crew to hospitality staff at venues, unions are advocating strongly for fair wages and conditions. Experienced venue operators know that ignoring this reality can mean bad press or even shutdowns due to strikes. High-profile labor actions (from Broadway theaters to major festivals) in recent years underscore that unions will flex their muscles if pushed – so it’s far better to work with them than against them.

Union-Heavy Markets vs. Right-to-Work Regions

Union influence isn’t uniform everywhere; it varies greatly by region. In union-strongholds like New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, London, or Paris, it’s almost guaranteed that if you operate a sizable venue, union labor will be involved in some aspect of your events. Some city-owned venues require all technicians and stagehands to be union members by contract or law – for example, a historic municipal theatre might insist that you hire union stagehands for any concert or show. By contrast, in so-called “right-to-work” areas (certain U.S. states in the South, for instance), venues aren’t legally obliged to use union labor. However, right-to-work doesn’t mean unions are nonexistent; many large convention centers or arenas in Florida, Texas, and other right-to-work states still employ union crews because of their expertise and to ensure consistent technical standards across events. The key takeaway is: always know what kind of labor environment you’re operating in. If your venue is in a union-heavy market, plan on working within those structures. If you’re in a region with less union presence, you may have more flexibility – but even then, touring productions might bring union requirements with them (for instance, a touring Broadway show’s contract might stipulate union hands for load-in).

Global Differences and Trends in 2026

Around the world, the picture varies. In North America, IATSE stagehands, IBEW electricians, and Teamsters truck drivers are mainstays in major cities. Canada’s large venues mirror U.S. union norms in cities like Toronto or Vancouver. Across Europe, formal union rules can be a bit less omnipresent for rock/pop venues, but strong labour laws fill much of the gap. Countries like Germany or France may require certain staff conditions (limits on working hours, generous breaks, etc.) whether or not a union is present. The UK often operates with a mix of union and non-union crew in live events, but you’ll still encounter unions like BECTU for theater technicians or the Musicians’ Union for orchestra gigs. Australia and New Zealand have industry awards that set minimum pay rates – effectively similar to union contracts even if crew aren’t all card-carrying union members. Meanwhile, in some Asian markets, you may find fewer formal unions in venue production, but don’t let that fool you into dropping standards – savvy international promoters still treat crews well and follow local labor laws closely. Across the board, 2026 has heightened awareness of crew welfare. Whether via union negotiations or industry-wide movements, there’s increasing pressure on venues to offer decent pay, reasonable hours, and safe working conditions for the people behind the scenes.

Turn Fans Into Your Marketing Team

Ticket Fairy's built-in referral rewards system incentivizes attendees to share your event, delivering 15-25% sales boosts and 30x ROI vs paid ads.

Navigating Local Union Rules and Contracts

Do Your Homework: Know the Rules Before You Book

One of the biggest mistakes a venue operator can make is to “assume” how union labor works at their venue. Every city and venue can have its own labor agreements and practices. Before you even finalize an event booking, research the local union landscape. Is your venue a “union house” (requiring union labor for all events)? If not, are there specific tasks that unions have jurisdiction over? For example, many U.S. arenas and convention centers mandate union riggers for anything hung from the roof, or union loaders for any trucking of gear. Many theaters require union ushers or box office staff, not just backstage crew. Don’t wait until show week to find this out. Contact the relevant union locals or a venue colleagues’ network early on. Venues that run smoothly have managers who establish relationships with union business agents well in advance. By reaching out 3-6 months before a major event, you can clarify exactly which roles must be union, what the crew calls should look like, and negotiate any exceptions if possible. For instance, if a touring production has its own trusted video technician, can they work alongside (not replace) a union video tech rather than having to hire two extra people? In some cases, local unions will allow a visiting specialist to work provided a union member shadows them, which means you pay one extra person to observe. Knowing these nuances ahead of time will prevent nasty surprises on your labor invoice — or show-stopping disputes on the day.

Demystifying Union Contracts (CBAs)

If your venue is a union house, there will be a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) in place between the venue (or a contractors’ association) and the union. At first glance, these contracts can be intimidating – dozens of pages of clauses, pay scales, and work rules. But it’s crucial to understand the key points in your local union’s CBA. Important sections to review include:

Ready to Sell Tickets?

Create professional event pages with built-in payment processing, marketing tools, and real-time analytics.

- Wage Scales and Job Classifications: The contract will list hourly rates for each role (e.g. stagehand, rigger, lighting board operator, head carpenter, etc.). Often there are different tiers – a base rate for general stagehands and higher rates for specialists or department heads. Make note of these rates; they will form the backbone of your labor budget.

- Overtime Triggers: The CBA will spell out when overtime pay kicks in (after how many hours per day or per week) and the multiplier (typically 1.5x or 2x normal rate). It may also define premium pay for overnight hours or holidays. We’ll delve into these rules in the next section.

- Minimum Calls and Staffing Minimums: Most agreements require minimum hours of pay for any call (often 4 hours), and some stipulate minimum crew sizes for certain activities. For example, the contract might say any load-in calls require at least 8 stagehands, or if the house is opened to the public, at least 2 union spotlight operators must be on duty – regardless of actual need. Highlight these requirements in your copy of the contract.

- Breaks and Meals: The CBA will state how often crews must get rest or meal breaks, and what penalties apply if they don’t. (Typically a meal break by 5 hours into a shift, with financial penalties if not provided.)

- Jurisdiction and Scope: This defines what work the union labor must do versus what can be done by others. It might say all “scenic installation” is union jurisdiction – meaning if you or the artist’s team want to do some stage decorating, technically you’d have to call in union carpenters to do it. Know these boundaries to avoid overstepping.

- Grievance and Arbitration Procedures: Hopefully you never need to use these, but it’s good to know how disputes are handled. There will be a process for the union steward or representative to raise issues and a path to arbitration if needed. Understanding this chain of communication can help you address issues the right way if they arise (more on conflict resolution later).

Pro tip: Don’t go it alone – talk to others who’ve managed events at your venue or similar venues. Often, experienced production managers or venue operators can summarize the “greatest hits” of a union contract in plain English. For example, a veteran stage manager might tell you, “This city’s stagehands get time-and-a-half after 8 hours, double-time after midnight, and they always take a meal at the 5-hour mark – no exceptions.” That one sentence is gold, summarizing the core things you need to plan around. Use industry contacts, or consider hiring a production consultant, to get up to speed on local rules if you’re new to a venue.

Local Laws and “Prevailing Wage” Requirements

Beyond union contracts, remember that government labor laws overlay everything. Many countries have laws about overtime (e.g., in the EU many workers can’t legally work more than 48 hours a week on average), mandatory rest, and minimum wages. In some cases, local law might mandate overtime pay even if your staff aren’t union – effectively making non-union crews follow similar rules to unions. One concept to know is “prevailing wage.” This is common in parts of the U.S. when events occur on public property or use government funds. Prevailing wage laws require you to pay workers according to rates set by the local authorities (often pegged to union wage scales). For instance, San Francisco mandates prevailing wages for event workers on city property – meaning even if you somehow hired non-union labor, you’d still have to pay them the same as union rates. The idea is to prevent undercutting and ensure fair pay across the board. If your venue is municipally owned, or you’re producing an event in a city park/plaza, definitely check if prevailing wage laws apply. Non-compliance can lead to fines or even your event being shut down by city inspectors. Similarly, some cities have specific requirements like hiring off-duty police (who might be unionized) for security, or using union electricians for any high-voltage work, etc. The bottom line: do your due diligence on both union rules and local laws any time you plan an event, especially in a new city. As one motto goes, “Know the rules well, so you can break none and bend a few if needed.” When you’re knowledgeable, you can sometimes negotiate minor adjustments or at least plan smarter within the constraints.

Key Union Work Rules: Compliance 101

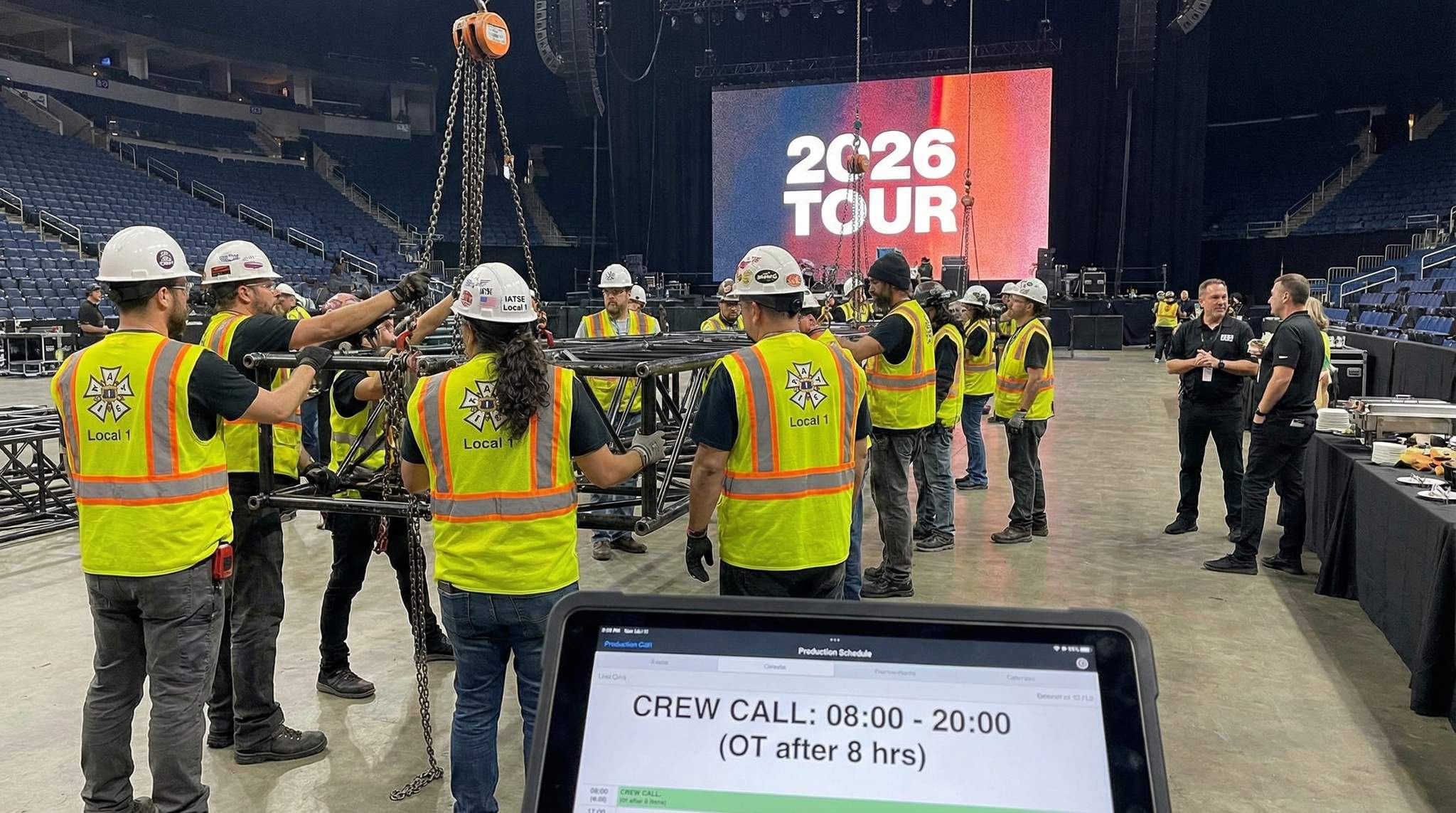

Standard Workday Length and Overtime

The defining feature of union crew labor is the structured workday. Unlike some non-union crews who might work 10-12 hours straight at a flat rate, union agreements usually define a standard day as 8 hours. After that, overtime pay kicks in. The typical pattern in many agreements is:

- Time-and-a-Half (1.5x) after 8 hours in a day. For example, if a stagehand’s base rate is $40/hour, the 9th hour of work in that day costs $60.

- Double Time (2x) after 12 hours in a day (and sometimes for any work in late-night hours, such as post-midnight). Using the same example, hour 13 would cost $80 at double rate.

- Weekly Overtime: Many contracts also stipulate overtime if a person works more than 40 hours in a week, even if no single day went over 8. And a 7th consecutive day of work is often double-time by default, while some contracts even make the 6th consecutive day 1.5x.

What does this mean practically? It means staffing schedules are critical. If you have a single crew do a marathon 16-hour load-in, be prepared for the cost to balloon after hour 8. Let’s illustrate with a simplified example:

Boost Revenue With Smart Upsells

Sell merchandise, VIP upgrades, parking passes, and add-ons during checkout and via post-purchase emails. Increase average order value by up to 220%.

| Scenario | Crew Hours Each | Base Rate | Overtime Hours (1.5x) | Double-time Hours (2x) | Total Labor Cost for 1 Crew Member |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-union crew, 10-hour shift (no OT) | 10 hours | $25/h | 0 (flat rate) | 0 | $250 (if paid as flat day rate) |

| Union crew, 10-hour shift | 8 + 2 hours | $40/h | 2 hours at $60/h | 0 | $8×$40 + 2×$60 = $400 |

| Union crew, 14-hour day | 8 + 4 + 2 hours | $40/h | 4 hours at $60/h | 2 hours at $80/h | $8×$40 + 4×$60 + 2×$80 = $640 |

In this rough example, a non-union technician might cost $250 for a long day, whereas a union technician costs $400 for a 10-hour day – and $640 for a 14-hour day. The rates and rules vary city to city, but the principle stands: long days get expensive. That’s why smart venue managers break work into shifts and avoid scheduling anyone for ultra-long days when possible. It can literally save thousands of dollars and also keep the crew safer (no one is at their best after 14 hours up a lighting truss). Remember, union crews will not “stick around for free” just to get the job done – if your show runs late or load-out drags on, expect to pay for those overtime hours. Plan accordingly.

It’s also worth noting overnight hours and holidays usually command premium pay. Many union contracts specify that any work between midnight and 7am is paid at double time, even if the person hadn’t hit 12 hours yet. Likewise, unions often charge time-and-a-half or double for working on a Sunday or on federal holidays. Know these “special” rates in the contract and try to avoid scheduling work during those times unless absolutely necessary (or budget extra for it). For example, if you can schedule load-out on Monday morning instead of overnight Sunday right after a show, you might cut labor costs significantly – and your crew will thank you for the rest.

Grow Your Events

Leverage referral marketing, social sharing incentives, and audience insights to sell more tickets.

Turnaround Times and Rest Requirements

Another critical rule in union labour (and increasingly in general labor laws) is mandatory rest time between shifts. This is often called “turnaround.” A typical requirement is at least 8 hours off between the end of one shift and the start of the next. Some agreements even require 10 or 11 hours off (for instance, certain film/TV crew unions demand 10+ hours rest). If you violate this, the union contract will impose a penalty, commonly that the worker is paid at overtime rates until they do get the minimum rest. Let’s say your riggers finish tearing down a stage at 2am, and you have them back at the venue at 8am (only 6 hours later). Those riggers might earn double-time starting at 8am and continue at that rate until 10am, because they were shorted 2 hours of rest. Beyond cost, think about safety: fatigue is a major risk in event production. A crew member who hasn’t slept enough could injure themselves or others. Professional venue managers treat turnaround rules as gospel. As one veteran put it, “If we load them out past midnight, they’re not back until at least 8 or 9 the next morning – no exceptions.” Build your schedule with realistic breaks between days. If you must do a crazy overnight (e.g., an arena converting from a basketball game to a concert by next day), consider having two separate crews: the overnight crew and then a day crew, so no individual works nonstop. Indeed, the most efficient venues often use relays of crew to stay within safe hour limits. For example, an arena might bring in a fresh team at 11pm to carry on a conversion that another team started at 3pm. This way, nobody exceeds 8-10 hours, and the work continues 24/7 in shifts. Such coordination takes effort, but that’s how places like major arenas get flipped for events at record speed (the United Center in Chicago famously transforms from one sport to another in under 3 hours with a 50-person crew) (www.ticketfairy.com).

Meal Breaks and Penalties

One of the easiest ways to run afoul of a union contract is by missing a meal break. Unions (and human beings in general!) rightly insist on meal breaks during long shifts. A common rule is a 1-hour lunch/dinner break by no later than 5 hours into the shift. Some contracts allow a shorter 30-minute break if a hot meal is provided on-site. If breaks are not given, meal penalties apply – essentially a fine paid to each worker. For example, a union contract might state that if a crew doesn’t break by the 5th hour, then starting at hour 6, each crew member accrues an extra hour’s pay at 1.5x rate for every hour until break. This can snowball quickly. Imagine you have 40 stagehands and due to a delay, you keep working through what should have been their lunch. By the time they finally eat, each person has 1 or 2 hours of penalty pay. You might be on the hook for dozens of hours of extra pay because you skipped a 1-hour break – a very expensive tradeoff!

Operationally, the solution is meticulous scheduling. Treat crew meal breaks as non-negotiable items in your production timeline. If your schedule is so tight that you think “we can’t stop or we’ll fall behind,” that’s a red flag – build in a buffer or stagger breaks. Many venues stagger crew meals: e.g., half the crew goes at 1:00pm, the other half at 2:00pm, so work never fully stops but everyone gets fed. Or, schedule a pause in rehearsals or soundcheck to let the tech team eat. Providing catering on-site is highly recommended; it can shorten how long people are away and demonstrates you care about their well-being. In some union agreements, having a catered meal can allow a “walking meal” – a shorter paid break where crew eat quickly and get back to work without incurring penalties (the tradeoff being you’re paying them during that break, but that’s often cheaper than a penalty). Check your contract for this clause. Also, remember special dietary needs – a vegan or gluten-free crew member won’t be happy if the only food is pizza. A bit of care in meal planning goes a long way to maintaining morale.

One more thing: Don’t assume crew can just “grab a snack when they have a minute.” While a flexible non-union crew might do that, union rules formalize break times for a reason. If an inspector or union steward is present, they will note if people didn’t take an official break. Even if the crew personally says “it’s fine, let’s push through,” that can come back to bite you (they could file a grievance later, or you set a bad precedent). The safest course is to always provide proper breaks on time. Your production will run better with a fed, rested crew anyway.

Minimum Call Times and Staffing Requirements

Unions often ensure a guaranteed amount of work (or pay) for their members through minimum call times and crew size requirements. A minimum call means even if a worker is only needed for an hour, you pay them a minimum number of hours – commonly 4 hours. For venue managers, this means you should avoid very short tasks at odd times. If you just need a couple stagehands to plug something in for 30 minutes, see if you can schedule that task to coincide with a larger call, or accept that you’re paying 4 hours for 0.5 hours of work. Perhaps find other useful work for them to fill the remaining time (maintenance, cleaning, etc.) so the time isn’t wasted. Also be mindful that splitting calls within one day might each incur separate minimums. If you send a crew away at 12pm and call them back at 6pm, that could be two separate 4-hour minimum payments, whereas if they just stayed through (with breaks) you’d pay straight through (though watch their overtime in that case!).

Crew staffing minimums mean certain departments or tasks require a set number of workers regardless of actual need. For example, a contract might dictate that operating a spotlight requires 2 people (one operator and one assistant) even if one person could technically do it. Or if any rigging work is done, at least 3 riggers must be called in. These rules are often tied to safety – having extra hands to spot each other – but sometimes are simply a way to ensure employment. You might chafe at having to hire six people when you think four could handle it, but it’s usually non-negotiable under the contract. Plan your budget around these numbers. If you know the union requires a minimum of 1 electrician, 1 carpenter, 1 sound, 1 lighting, etc. for any show, then even a tiny event in a big union venue will have a baseline labor cost. This can influence what rentals or small events you accept at your venue; you need to charge clients enough to cover the crew union minimums or you’ll lose money on small shows.

Additionally, many union agreements require that department heads or “key” personnel are present for any work in their department and that each department has a designated lead. That means if you have any lighting work going on, you must have the Head Electrician (a higher-paid lead) on duty overseeing it. Same for sound (Head Audio) or staging (Head Carpenter). For venue management, this means even if a touring production brings their own LD (Lighting Designer) to run the show, you might still be required to have your union Head Electrician present (and on the payroll) during the show in case of issues or simply to fulfill the contract. These heads are usually billed at a premium rate. It’s wise to factor at least 3-4 “core” leads into every event’s labor plan: one each for lighting, audio, staging, and possibly video or rigging, depending on your venue setup. They might be working hands-on, or just supervising, but either way they’re on the clock. The positive side is that these senior crew can be your allies – they are often very experienced and can help things run safely and on time. Build a good rapport with them (more on this later in Crew Harmony) and they’ll often help save you money by working efficiently and advising on the best crew setup for a task.

To sum up, union work rules are all about structured fairness: fair pay for long hours, fair breaks for hard work, fair minimum employment. From a compliance standpoint, if you respect these rules, you’ll avoid most conflicts. The union steward (if present at your venue) will see that you’re running things by the book – giving breaks on time, not running folks into the ground, hiring the proper crew complement – and they’ll be far less likely to lodge grievances. Much like how you treat artist riders or safety regulations, union rules are an essential part of show planning. By mastering them, you turn a potential minefield into a manageable routine.

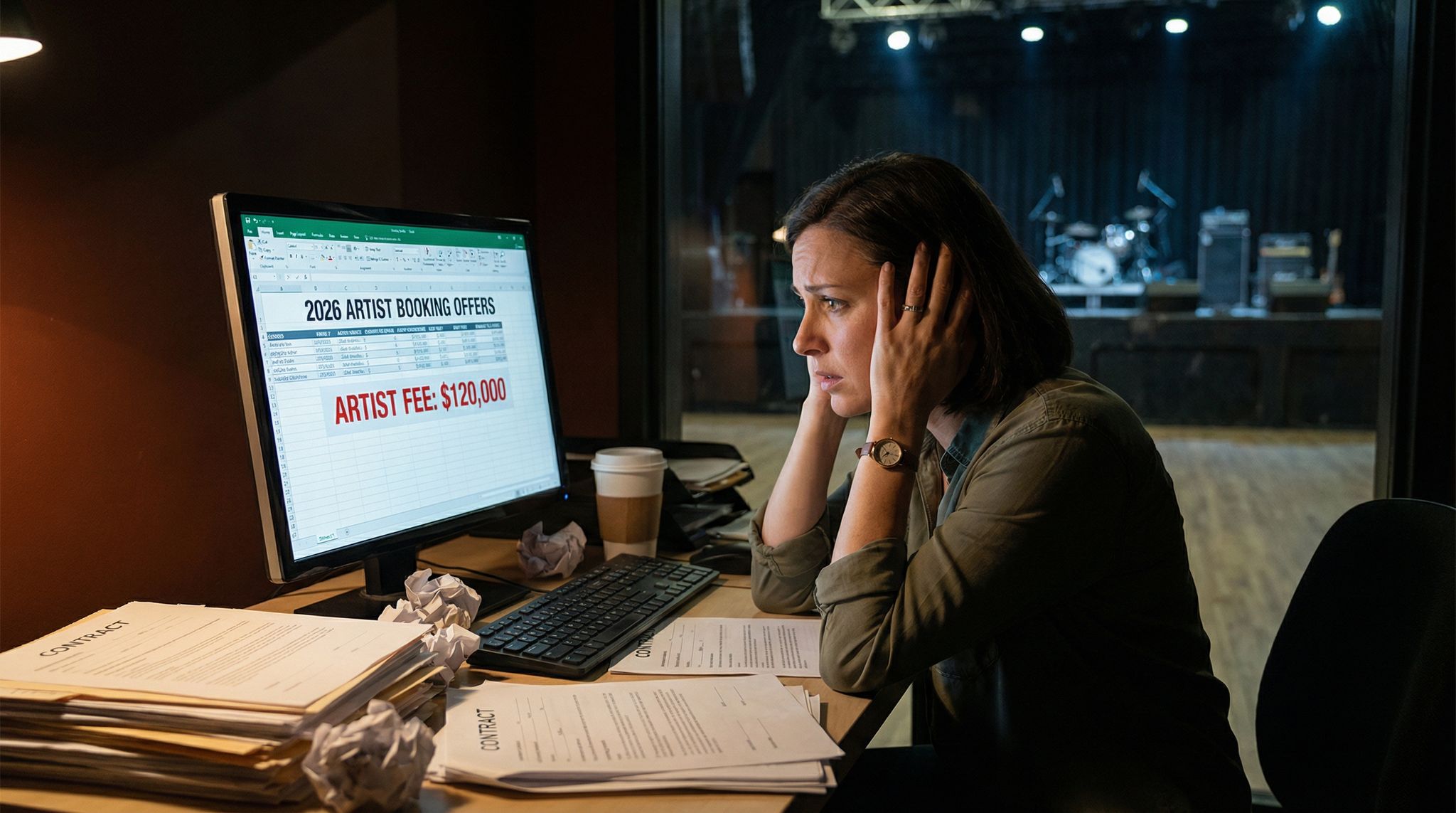

Budgeting for Union Labor Costs

Higher Base Wages and Benefits

It’s no secret that union labor costs more per hour than entry-level non-union labor. But it’s important to appreciate what you’re getting for that cost. Union crew members are generally trained, certified where needed, and bring years of experience – and their pay rates reflect that. In many cases, union stagehands also receive benefits like health insurance and pension contributions (often built into the hourly rates or added on top). For instance, you might see in a union contract that the base wage is $40/hour, but the venue also contributes an additional percentage to a benefits fund. When budgeting, account for the fully loaded cost, not just the base wage. A “$40/hour” stagehand might effectively cost $50+ after payroll taxes, benefits, and union fees are added. Some contracts explicitly list these add-ons: e.g., “Hourly rates include 10% vacation pay and 10.4% pension”. That means out of that wage, part is earmarked for those funds. It’s still real money out of your budget, but at least you know it’s funding a stable workforce (which can translate to lower turnover and higher reliability – intangible benefits for your venue).

Unions also tend to negotiate regular raises. If your venue’s union contract was signed in 2024 with 3% annual wage increases, you need to build those increases into forward-looking budgets. Don’t price an event for 2026 using 2024 labor rates, or you’ll come up short. Always use the most current rate sheet. Many venues keep a summary sheet or calculator on hand – for example, a spreadsheet where you plug in how many of each crew and hours, and it computes costs with the current rates. If you don’t have one, consider making it (or ask the union office, which might even provide one). This helps in giving clients quotes too – you can say “Here’s the labor cost for your event” with confidence if it’s systematically calculated.

How much higher are union wages? It varies, but as a rough ballpark, base rates might be anywhere from 20% to 100% higher than non-union gig workers, depending on the market. For example, a non-union stagehand might make $20–25/hour in a smaller city, whereas a union stagehand in a major city could be $35–$45/hour base. Specialist roles can command even more; a union head rigger or video engineer could be $50–$80/hour. And remember those are straight time rates – overtime pushes them higher. In one California performing arts center, a union master electrician earns about “$86/hour for straight time and $129/hour in overtime”. Even a mid-level union tech in that venue makes around “$75/hour base pay”. These figures underscore why careful planning is needed: the labor bill for a single busy night can run tens of thousands of dollars at large venues.

The best approach is transparency in budgeting. If you’re a venue renting to promoters or clients, be upfront that union labor is required and provide an estimate of those costs early. Nothing causes more friction than a surprised client who didn’t realize that “$5000 for staff” line item was per day. Educate them (without blaming the union) – explain that these are professional crew who ensure the event’s success. Many experienced promoters know and respect union labor, but newcomers might not. It can help to share success stories: for example, how the union riggers’ expertise prevented any delays during a complex load-in, or how the union crew’s efficiency actually saved hours (and therefore money) on the back end. When clients see the value, they’re more willing to bear the cost.

Planning for Overtime and Penalties

Even with smart scheduling, there will be events where overtime is unavoidable. Maybe an artist shows up late so your crew goes long, or a doubleheader event means back-to-back shifts. The key is to budget assuming you will have some overtime, rather than hoping you won’t. A good rule of thumb is to add a contingency percentage to your labor budget. For example, some venue managers will add 10–15% on top of the initial crew cost estimate as an “overtime cushion.” If you don’t use it, great – you come in under budget. But if a headliner encores for 30 minutes past curfew, you’ve got the buffer to pay the crew’s extra half-hour at premium.

Know the specific overtime triggers and costs for your venue, and plug those into projected scenarios. For instance, if you have an all-day festival using your venue from 10am to 11pm, you’re looking at 13 hours – which for union crew means 5 hours of overtime pay each. Calculate that from the start; don’t pretend you can magically make a 13-hour event happen with 8-hour costs. If the budget looks scary, consider shift rotations to mitigate the overtime. It might be cheaper to hire a second set of hands for part of the day than to pay one set 5 hours of time-and-a-half. Weigh it out: e.g., instead of 10 crew for 13 hours (with OT), maybe 15 crew split into two groups so that no one goes beyond 8-10 hours. You’ll pay more people for fewer hours each. Sometimes the total cost is similar, but you gain safety and freshness with people working shorter shifts.

Also plan for inefficiencies. Live events are living things – sets run late, trucks get stuck in traffic, equipment fails and needs fixing. Any such delay could mean extra labor time. One strategy is to schedule crew calls slightly longer than you think is needed, so you’ve built in an overtime allowance on paper. For example, if you think strike will go until midnight, budget the crew until 1am – that covers you if it runs long, and if it doesn’t, you saved a bit. Be mindful of the minimum call though; if you add too much padding you might pay for unused time. It’s a balancing act.

Don’t forget weekends and holidays. If your event is on a Sunday, some contracts treat all Sunday hours as 1.5x pay regardless of length (because it’s a traditional day off). Holiday shows (e.g., New Year’s Eve) could incur double time all day. These things should be identified upfront. Mark your calendar of events with a star for any such dates and triple-check the contract on how they’re handled. Many a venue has lost money by agreeing to a show on a public holiday and not factoring in that crew costs would be double.

Finally, factor in potential meal penalties or other fines in a worst-case scenario. While you should aim never to incur them, set aside a small budget line for “contingency – union penalties.” Even 1-2% of the labor budget reserved for this can cover you if something goes wrong. It’s like insurance. If you manage everything perfectly (no penalties), you can reallocate that bit to something else or count it as savings. But if the day goes haywire and you miss a break, you won’t be scrambling to justify unplanned costs to your finance team or client.

Smart Scheduling to Control Labor Costs

One of the most powerful tools a venue manager has to manage union labor costs is the schedule. Thoughtful scheduling can be the difference between a crew coming in at base rate or racking up hours of overtime. Here are key scheduling strategies:

- Stagger start times: Not every crew member needs to start at the beginning of the day. For example, if doors open at 6pm for a concert, you might start some technicians at 10am for load-in, but hold off on calling spotlight operators or extra hands until 2pm or later. Those later folks can then work the show and load-out and still be under 8 hours total. Meanwhile, the early crew might leave after sound check and not stay the whole event. Case in point: a large music festival had its core stage setup crew begin at 6am, but brought in a second shift of crew at 4pm to handle the evening headliner changeovers and final load-out. The morning crew hit 10 hours by late afternoon and went home, avoiding the costly overnight double-time, while the fresh second shift took the event through to conclusion on straight time and a bit of overtime. The result was two groups each doing ~10 hours instead of one group doing 16-18 hours, which keeps people fresh and prevents burnout.

- Plan around natural breaks: If your event has a long downtime (say a conference has an afternoon break with no sessions), use that to your advantage. You might be able to release some crew and call them back later, or stagger the meal break for everyone during that lull. Similarly, if a concert has an opening act at 7pm and the headliner not until 9pm, you could theoretically have some stagehands finish their work at 7:30pm and not stick around (especially if the headliner’s crew handles on-stage changes). Coordinate with production managers to see if you need all local crew for the entire show or just for certain parts. If local union rules allow crew to be dismissed (sometimes you have to guarantee a minimum hours, as discussed), take advantage when the work is truly done.

- Use dark days for heavy work: If you have multiple show days in a row, consider scheduling the most labor-intensive tasks on days when you can afford any overages. For instance, if you have an empty day before a big show, do as much setup then as possible, so show day crew call can be later and shorter. Or if you know the second night of a two-night run has no show the next day, you could decide to load-out that night even if it runs late (since no one needs to be back early). In contrast, if a load-out must be done overnight and you do have another event next morning, strongly consider bringing in a fresh overnight crew to handle it, letting the day crew go home to rest – yes it’s more total people, but otherwise you’ll pay massive overtime and have a tired crew by morning.

- Optimize crew size vs. hours: There’s often a trade-off between the number of crew and the length of the shift. Fewer crew could mean things take longer (possibly pushing you into OT hours), whereas more crew might get it done within straight time. Find the sweet spot. For example, could adding 2 extra stagehands on the load-in save an hour or two? If so, that might actually be cheaper than everybody staying late. Consult your department heads on these decisions – they often know exactly where an extra person would speed things up or where it’s already efficient. Also, if union rules require paying a minimum number of crew regardless, use them! If you must hire 8 stagehands but the task only needs 6, assign the extra two to start prepping another area or double up on teams to finish faster. Use the manpower you’re paying for to potentially reduce overall hours.

To illustrate smart scheduling, consider this simple comparison table:

| Approach | Crew Count × Hours (each) | Total Labor Hours Paid | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Shift (small crew, long day) | 10 crew × 12h = 120 crew-hrs | 120 + overtime (10×4 OT hrs) = 160 hrs cost | Crew hits 4 hrs overtime each (expensive; fatigue risk) |

| Staggered Shifts (larger crew, shorter shifts) | 15 crew × 8h = 120 crew-hrs | 120 hrs cost (all straight time) | More crew but nobody hits OT; work finished within 8h |

Both scenarios get the work done (120 crew-hours of effort needed). The first uses fewer people longer – incurring 40 hours of overtime pay in total. The second uses more people to finish faster – zero overtime. Even if the base pay costs equal the overtime premiums in pure dollars, the second scenario keeps everyone in straight time and likely happier/safer. In many cases, it actually saves money too (since OT is 1.5x and you didn’t pay that by adding folks). This example will vary with actual numbers, but it demonstrates why throwing more crew at a job for a shorter duration can be smarter than burning out a small crew over a long haul.

Avoiding Surprise Costs

A few extra budget tips to avoid unwelcome surprises:

- Double-check call times and end times when advancing shows. If a band insists on a 7am load-in on a Sunday, red flags should go off for both early hours (overnight premiums if crew came in super early) and it being Sunday (possibly premium pay). You might negotiate that to a reasonable time or day if you catch it early.

- Set clear curfews and communicate them to artists/promoters. If your labor budget only covers until 11pm, and you know going past will cost thousands more, make sure everyone knows the plan. Often artists are flexible on encores or meet-and-greets if they understand there’s a hard cost (and maybe a hard union cutoff) after a certain time. Some venues even have clauses in artist contracts that if the show runs past X time, the additional labor cost will be charged to the promoter/artist. That tends to ensure shows finish on time!

- Confirm the holiday schedule each year. Unions typically treat specific days as holidays (e.g., New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, etc., plus sometimes others like Labor Day or local civic holidays). If an event falls on one of those, know it well in advance. Also, note what time a “holiday” kicks in – often if a show goes past midnight into a holiday, the higher rate could start then. For example, if July 4 is a holiday and your July 3rd show loads out past midnight, you might pay holiday rates after 12:00am.

- Keep good records of crew calls and breaks. Mistakes in time-keeping can cost money. If a crew member claims they worked longer or didn’t get a break, and you have no record to verify, you’ll likely have to pay the claim. Use sign-in sheets, or digital time tracking if available, and have crew chiefs note break times. This protects you from over-billing and also builds trust with the union (they see you’re tracking things properly). As the saying goes: “If it isn’t written down, it didn’t happen.” Detailed logs can resolve disputes quickly by referencing exactly what happened.

In summary, budgeting for union labor means embracing the reality that labor will be a significant line item – but also one you can manage proactively. Plan for the worst, communicate costs early, and find creative ways to work within the rules. Many venues that initially struggled with union costs have learned to thrive by honing their scheduling and labor planning skills. They treat the union crew as partners in problem-solving: e.g., asking the union department heads “how can we do this changeover efficiently to minimize overtime?” – you’d be surprised, they often have great suggestions. After all, the crew wants a smooth day too; no one actually loves working 16-hour days even with extra pay, if it can be done in 10 with proper planning. That brings us to the next crucial part: turning the crew, whether union or not, into a cohesive team.

Blending Union and Non-Union Teams

Defining Roles and Avoiding Overlap

Many venues employ a mix of union and non-union personnel. Perhaps your core full-time operations staff (like technical directors, event managers, or some AV techs) are non-union, but you bring in union stagehands for show days. Or maybe touring productions bring their own road crew who work alongside local union crew. In these situations, role clarity is paramount. You must ensure everyone knows who does what to avoid conflict. The risk is that a well-meaning non-union staffer might start performing tasks that the union crew is supposed to handle (or vice versa), leading to grievances. For example, if your non-union production manager starts pulling cables or climbing the truss to adjust lights, union stagehands may object – that’s their job. A classic rule in union venues is that only union personnel unload and move gear from trucks; if a eager volunteer or band member starts grabbing cases, union crew can legitimately protest. The simple solution is to communicate these boundaries: inform all non-union staff and volunteers beforehand about what tasks are respected on show day in a union house. Many venues create a brief “labor ground rules” memo for visiting production teams which says, for instance, “Please note: House crew will handle all loading in/out of equipment. Visiting team should direct and supervise as needed, but not physically carry gear (per venue union rules).” This heads off most issues.

To further smooth operations, consider creating a scope of work document for each event that outlines union roles vs. others. For example: “Union lighting techs will hang and focus lights – touring LD will program the console; House carpenters will assemble staging – tour crew can place set dressing once stage is set,” etc. Share this with the union crew leads and the tour manager in advance so everyone agrees. It can be as simple as an email, but writing it down makes it clear. By defining roles, you not only prevent stepping on toes, you also ensure things don’t fall through the cracks. Each task is assigned to either union crew or non-union personnel, so there’s no ambiguity about, say, who’s responsible for plugging in the PA versus who tests it.

Sometimes, you’ll be contractually obligated to have a union member shadow any non-union worker who is doing certain tasks. For instance, at some venues if you bring an outside audio engineer (non-union) to run the show, the house might require a union A1 (lead audio) to sit at front-of-house with them or be available on standby. This can feel redundant (and indeed you’re paying for two people where one could do the job), but it can also be seen positively: the union tech is there as a backup and knows the venue’s system intimately. The best practice in those scenarios is to turn the “shadow” into a collaborator, not a potted plant. Introduce the touring/non-union engineer to the union house audio lead and encourage them to work as a team. The union person can help patch the stage, troubleshoot venue gear, communicate with other house staff, etc., while the visiting engineer focuses on the mix. When each person’s role is respected, these pairings work well. It’s when one is sidelined or one overreaches that ego clashes happen.

The Buddy System for Mixed Crews

A great technique venues use when mixing union and non-union teams is a “buddy system” or pairing structure. Essentially, for every department, designate one union lead and one non-union (or visiting) lead to coordinate together. For example, pair your house’s union head carpenter with the tour’s production manager, or your union lighting lead with the visiting lighting designer. They make a plan together and then direct their respective sub-teams accordingly. This fosters mutual respect because each “buddy” recognizes the other’s authority and expertise. The union lead ensures union rules and safety protocols are followed, while the non-union counterpart brings in the specific needs or preferences of the artist or promoter. They act as co-leaders rather than rivals.

For smaller events, you might pair individuals: say, one union stagehand and one venue staffer working side by side on a task. The union person can teach proper technique (and make sure nothing violates rules), and the staffer can help while learning. Over time, these relationships build trust. The union crew sees that the venue’s regular staff aren’t there to cut them out or demean their work – they’re part of the same production, just under a different employment status. Meanwhile, your full-time staff become adept at working in union settings without accidentally causing friction.

Another benefit of the buddy approach is knowledge transfer. Each side has something to offer. Perhaps the union folks have decades of technical know-how, while your younger non-union staff might be savvy with new technologies or social media aspects of events. Encourage a culture where skills and ideas are shared openly. A union electrician might show your intern a safer way to run cable, while the intern might share a quicker way to do digital check-ins or something – it’s a two-way street. When people start learning from each other, that “us vs. them” wall tends to come down.

Fostering Mutual Respect

At the heart of crew harmony is respect. This sounds basic, but it’s easy for cliques and divisions to form: union vs. non-union, local vs. touring, full-time vs. part-time. As the venue manager, you set the tone that everyone is part of one team delivering a great event. Avoid language that reinforces division – for instance, say “the stage crew” or “our production team” rather than “the union guys” or “our staff versus their staff.” In safety briefings or kickoff meetings, include everyone together. If you do a toolbox talk or run-through before doors open, have union and non-union crew all present and address them collectively. This sends a message of unity.

Be aware of subtle behaviors too. If the venue provides swag or catering, make sure it’s for all crew, not just your employees. One pitfall some venues have hit: giving venue staff t-shirts or free meals but not extending the same to union crew, which breeds resentment (“they think we’re second-class”). Instead, if you buy pizza after a long load-out, order enough for the whole crew and invite everyone to dig in. These small gestures carry weight. Also, celebrate wins together – if a show went really well, thank the entire crew, not just the in-house team. You might even highlight specific contributions: e.g., “Big thanks to our union riggers for getting that truss up so quickly – that kept us on schedule, great job by everyone.” People like to have their work appreciated, and union crew are no different.

It’s worth noting that many union workers take pride in their professionalism. They’ve often invested in their training and take the job seriously. Conversely, some non-union folks (like volunteers or newer hires) might be very passionate but less experienced. By setting a culture of peer mentoring instead of elitism, you turn potential friction into collaboration. If a union veteran corrects a younger crew member, frame it as guidance, not scolding. Likewise, discourage any mocking of union rules by non-union staff (“haha, break time already?” remarks are not helpful). A respectful culture is one where crew members feel valued for their contributions regardless of where their paycheck comes from. As a manager, if you see any disrespect – on either side – address it swiftly but fairly. For example, if a union member tells a volunteer “stay in your lane, you don’t know anything,” have a private word that while the intent to maintain proper roles is right, there’s a better way to teach and communicate. And if a non-union staffer badmouths the union crew (it happens: “those guys are slow/overpaid/etc.”), nip that in the bud and remind them these crew are skilled professionals critical to the show’s success.

To highlight how effective respect and collaboration can be, consider how large festivals manage labor peace with mixed crews. Top festival producers treat all workers – union, volunteer, contractor – as part of one big team with a common mission. They often hold joint orientation meetings where everyone from the volunteer coordinator to the union crew steward stands together, hears the safety briefing, and gets pumped up for the event. Bringing that same spirit into a venue setting, especially for repeated events, can pay huge dividends in crew morale and loyalty, transforming the group into a more effective unit.

Fostering Crew Harmony and Morale

Joint Training and Orientation

One often-overlooked strategy for improving union-management relations is training together. If your venue hosts an annual emergency drill or customer service workshop, invite the union crew (especially regulars) to participate alongside your staff. For example, you could hold a pre-season safety training day that includes fire evacuation procedures, new equipment demos, etc., and make sure both union stagehands and house staff are present. This not only ensures everyone has the same knowledge, but it reinforces that the union crew are part of the venue family. And practically, it’s helpful: if an evacuation happens, it doesn’t matter who’s union or not – everyone needs to know their role in getting the crowd out safely, aligning with broader venue safety initiatives. Training together breaks down social barriers as well; people chat, share experiences, maybe even bond over coffee breaks.

Cross-training opportunities deserve a mention here too. Now, formally cross-training union workers into different jobs can run into jurisdictional issues, but many venues have found ways to broaden crew skills with union cooperation. For instance, you might work with the union hall to organize a special training on new AVL (audio-visual-lighting) technology that both union members and your in-house tech team attend. The union might send apprentices or junior members to learn, and your team learns alongside. Everyone benefits by becoming more versatile. Some progressive union locals encourage upskilling like this, knowing that a more skilled crew base makes the venue more successful (which in turn leads to more work for everyone). A real-world example: a major arena invested in training its changeover crew (mostly union laborers) to also handle basic AV setup for e-sports tournaments. They coordinated with the union to certify those interested in operating LED video panels and fast network setups. When the arena started hosting e-sports, they had a ready pool of union crew who could pivot from laying basketball courts one day to assembling massive video walls the next, illustrating how venues adapting to new event types like esports rely on upskilled technical crews.

Orientation isn’t just about skills – it’s also about welcoming and culture. At the start of a big project or season, consider a kickoff meeting that includes key union personnel. The venue GM or production head can share the vision: e.g., “This year we have 40 concerts on the books; we’re aiming for record attendance; we’re also focused on safety and efficiency.” Thank everyone in advance for their hard work. These moments help union crew feel seen as stakeholders, not outsiders. Some venues even hand out a venue-branded shirt or hat to union folks who work there frequently – basically extending the team colors to them. (Of course, not all union crew will wear a venue shirt versus their own black attire on show days, but it’s the gesture that counts.)

Empowering Union Stewards and Leads

Every union crew on site will typically have a steward or supervisor who is the point person for that crew. Instead of viewing the union steward as a “shop cop” policing your compliance, make them your ally. Early in an event or load-in, introduce yourself (if you haven’t met) and establish open communication: “If you see any issues or have concerns, let me know right away so we can fix them.” This proactive approach often catches small discontents before they escalate. For example, if a non-union intern accidentally wandered on stage to move something, a steward might raise an eyebrow. If you’ve invited the steward to speak up, they’ll come to you and mention it – giving you a chance to correct it or clarify roles, rather than it turning into a formal grievance later. A quick daily or pre-show check-in with the steward (like: “Hey, everything good with the crew today? Need anything?”) can work wonders and serves as a channel for any union crew grievances. It shows you respect their role and care about the crew’s well-being.

Likewise, union department heads (leads for lighting, sound, rigging, etc.) should be looped into planning. Share schedules and set change plots with them so they can anticipate crew needs. If a lighting lead knows there’s a complex 10-minute set change, they might quietly pre-rig some lighting or have extra hands ready, saving time. Treat these folks as you would any department manager on your team – because on show day, they are managing a piece of your team. Some venues invite their core union leads to production meetings alongside promoters or touring crew. This inclusion not only taps into their expertise (they might foresee a power issue or rigging challenge nobody else noticed), but it also demonstrates trust.

A note on conflict resolution: If a union member breaks a rule or there’s a job performance issue, resist the urge to address the individual directly in an angry or public way. Instead, involve the steward or union supervisor in the conversation. For instance, say a union crew member is repeatedly late or using their phone when they shouldn’t. Pull the steward aside, express the concern calmly, and let them handle it or at least be present when you talk to the person. Union crew have contractual protections, and the steward will ensure any disciplinary action follows the agreed process. By respecting that protocol, you avoid turning a minor issue into a labor dispute. In most cases, the steward will be grateful you approached them first and will resolve the issue quietly. From the crew’s perspective, this is seen as fair – you’re not chewing someone out in front of everybody or making unilateral threats; you’re working through the proper channels. In short, empower union leadership on the ground to help maintain order. They generally want a smooth gig as much as you do.

Recognizing and Incentivizing Great Collaboration

When union and non-union team members work seamlessly together, make it a point to acknowledge that. Positive reinforcement goes a long way in breaking down lingering divides. If, for example, your in-house techs and the union stagehands pulled off a flawless stage flip in record time, celebrate it. That could be a shout-out in the post-event debrief, a thank-you email to the whole crew, or even a small celebration (donuts in the breakroom next morning, courtesy of management). These gestures show that you notice cooperation and efficient work – and that you value it. Don’t fall into a trap of only giving kudos to your full-time staff and treating union crew like ghosts. They’re very much part of the success.

Some venues implement incentive programs that include union labor. For instance, a performing arts center might have a safety reward program: if the crew goes X days without an accident or injury, everyone gets a bonus or a meal. If you do something like that, definitely involve the union crew equally. At one large theater, management instituted a quarterly “crew MVP” award and made sure to rotate it between house staff and union stagehands who went above and beyond. In one quarter, the award went to a union flyman who engineered a clever fix to a stuck curtain just in time for show open; in another, it went to a house audio tech who trained several union newcomers on the digital console. This balanced recognition sent a message that excellence is excellence, no matter who’s payroll it’s on.

Building camaraderie can be as simple as providing space for it. If your venue has a crew catering area or green room, make it communal. When crunch time is over, encourage a culture where crew members can actually socialize a bit. It could be as informal as keeping the venue open an hour after load-out with some music on so folks can unwind together before heading home. These human moments are where friendships form – and once people are friends, the union/non-union distinction matters a lot less in their day-to-day interactions.

Real-world successful collaboration example: Many venues have quietly fostered stellar union-management relations. For instance, consider a famous arena in the U.S. Midwest (venue names aside, but known in industry circles) that hadn’t had a single labor stoppage or grievance escalation in over a decade. Their secret? Management and the union steward jointly run a “crew committee” that meets monthly to discuss any issues, suggestions, and upcoming challenges. When the venue upgraded its sound system, they invited senior union audio techs to planning meetings so everyone was on the same page technically (and no jurisdiction issues arose). During the pandemic, the venue management advocated for and secured extended healthcare coverage for furloughed union crew – earning immense goodwill. Post-pandemic, those crew returned the favor with flexibility on calls and helping train new hires. The result has been a stable, harmoniously blended team. The takeaway: by investing in the well-being and inclusion of union staff, the venue gained a loyal, cooperative crew that often goes above and beyond to make events successful.

Of course, not every venue will operate at such a gold standard of harmony – but it’s something to aspire to. And it’s achievable with consistent effort and goodwill. Next, we’ll look at how to handle the tougher moments when conflicts do arise, and how to turn them into opportunities for strengthening trust.

Handling Disputes and Building Partnerships

Proactive Conflict Resolution

No matter how positive your culture, disagreements can happen. The mark of a professional operation is how quickly and fairly those conflicts are resolved. First, it pays to have a clear chain of command for crew issues. As we mentioned, the union steward is usually first stop for union crew concerns. Make sure your floor managers and stage managers know: if a union crew member raises an issue to them, they should loop in the steward (if the crew hasn’t already). And vice versa – if a supervisor has an issue with a union worker, go to the steward or union head. This keeps communication flowing properly. It’s when people bypass these channels (or worse, let frustrations fester without talking) that little issues become big ones.

Let’s say a union crew member complains that a particular task isn’t in their job description (e.g., “The projectionist shouldn’t have to also run audio cables”). Right or wrong, take the complaint seriously and discuss it immediately. In that scenario you might gather the union lead, the person, and a production manager and quickly consult the work scope in the contract. If it turns out the crew member is correct, you simply assign the task to the right person (even if it means calling in another crew member and paying accordingly). If the crew member was mistaken, you explain the expectation and note that the contract allows it – ideally the steward backs you up if it’s clear. Either way, you solved it on the spot and everyone can move on. What you don’t want is the crew member stewing about it all show and then filing a grievance later because nobody addressed it, or feeling like you inadvertently did a union crew’s job.

Sometimes, you as the venue operator might be unhappy about something – say a union crew didn’t finish a setup by call time, causing a delay. Rather than explode in the moment, talk to the union department head privately. Use a problem-solving tone: “We were pressed for time at soundcheck. How can we avoid that? Do we need more hands or was something unclear in instructions?” This invites collaboration instead of blame. Maybe you discover there was a miscommunication or a missing tool. Fix that for next time. If it truly was a crew performance issue, the union head will often handle it internally (e.g., they might decide not to call that slower worker next time or give them a talking-to). In doing this calmly, you maintain a partnership vibe. A defensive, accusatory approach (“Your guys screwed up!”) would only make the union crew close ranks and resent management.

Keep a written log of any notable disputes or resolutions. This isn’t about building a case against anyone; it’s about having a record in case patterns emerge. For example, if meal breaks were missed on two shows in a row, your notes will remind you to investigate why – maybe the schedule is unrealistic or a particular stage manager keeps ignoring the clock. Or if one union crew member’s name keeps popping up related to issues, you can quietly ask the union to rotate in someone else. Documentation is also vital if anything ever does escalate to a formal grievance or arbitration – you’ll have the facts of what happened when. All supervisors should be noting events in a log to ensure accuracy. Moreover, documented feedback can be shared during labor-management meetings to continuously improve processes.

Formal Mechanisms and When to Use Them

Despite best efforts, occasionally issues can’t be fully resolved informally. That’s where the formal steps in the CBA come in. Typically, a grievance procedure might look like: verbal discussion -> written grievance -> meeting between higher management and union reps -> arbitration if needed. The goal is to never let it reach arbitration; that means both sides failed to settle it amicably. Arbitration can be costly, slow, and strain relationships. So, if a written grievance is filed, treat it as a serious fire to put out. Respond within the timeframe the contract stipulates and show that you’re willing to work it out. Many times, grievances are about money (like “we should be paid an extra 2 hours because XYZ”). If the amount is small and the union has a point, it might be worth simply paying and moving on, even if you think you were right. Consider it goodwill. For larger stakes or principle-based issues, you might need a sit-down with union leadership. Go into that meeting with an open mind and all your documentation. Also, try to understand the union’s perspective: are they worried about a precedent being set? Do they feel someone was treated unfairly? If you can address the root concern, the settlement becomes easier.

One thing to remember: the union and the venue ultimately have a common interest – successful events with happy clients and steady work. Reminding everyone of that can refocus a contentious discussion. You might say in a meeting, “We all want these shows to go well so that the promoter comes back next year, which means more work for all of us. Let’s figure out how to ensure this kind of mix-up doesn’t happen again.” Now it’s not management vs. workers, it’s team-fixing-a-problem. In fact, your resolution might involve both sides compromising or doing something differently. For example, after a dispute about a volunteer doing union work, you might agree to brief volunteers more strictly (management action) and the union might agree that on future events the steward will proactively remind volunteers of boundaries too (union action). Both take responsibility.

If you do reach a settlement on an issue, follow through on it religiously. Nothing erodes trust faster than making a deal and then ignoring it later. If you promised to always schedule a second spotlight operator for safety after a grievance about solo operation, then make sure from now on you budget and schedule that second spot op. The union will notice that you keep your word, which makes them more inclined to be flexible next time a minor issue comes up.

Turning Challenges into Partnerships

Often, a crisis or conflict can be the catalyst for a stronger partnership going forward. Some venues actually credit a past dispute with ultimately improving communication. For example, there’s the case of a film festival that initially tried to bypass union projectionists and then had to scramble when protests arose – but after negotiating, the festival not only hired the union projectionists, they brought them on as advisors and the event ran better than ever. Instead of harboring grudges, both sides in that scenario built a bridge, involving labor organizations and political leaders to find a solution. The festival learned the value of skilled union operators, and the union appreciated the festival’s mission and became a supporter in making it succeed each year.

Another case study: A certain large theater had an adversarial relationship with its stagehands’ union years ago – constant grievances, slow work pace, open hostility even. When new management came in, they decided to reset the tone. They sat down with union leaders and acknowledged all the past issues, then asked, “What can we do better, and here’s what we need from you.” That frank conversation led to practical changes like better backstage equipment (management invested in new lifts and lighting so the crew could work more efficiently) and a new labor-management safety committee that met monthly. Over the next season, the grievance count dropped to near zero and productivity soared. By the time a huge touring production came in, the crew and management were so in sync that the tour producers raved it was the smoothest local crew they’d worked with. The punchline: that tour decided to make the theater a regular stop and even held an extended residency the following year – a win for the venue’s revenue and a win for union labor hours. It all started from confronting issues openly and committing to partnership.

If you’re facing a current labor challenge at your venue – maybe high costs, or crew dissatisfaction, or fear of unionization if currently non-union – try reframing it as an opportunity. Engage with your workers (union or not) about their concerns. Engage with union reps about your business concerns. Often, you’ll find both sides can take steps to help the other. Perhaps the union can offer a more flexible crew call structure for experimental events, and you in turn guarantee a minimum number of work calls per month. Creative solutions abound when people actually talk and trust each other. In 2026, some venues are even involving union staff in planning discussions for new technologies and workflows, ensuring buy-in from day one rather than imposing changes top-down. This inclusive approach tends to reduce resistance and build a sense of joint ownership of the venue’s success.

Know when to ask for help: If things are truly fraught, it’s okay to bring in an outside mediator or consultant. Organizations like the International Association of Venue Managers (IAVM) sometimes offer resources or can connect you with peers who’ve dealt with similar issues. There are also professional labor mediators who specialize in bridging gaps in entertainment and events. Sometimes an external perspective can find the win-win that eludes those entrenched in the situation. But in most cases, simply improving day-to-day communication and demonstrating mutual respect will steer you away from the brink of serious disputes.

Long-Term Relationship Building

The final piece of the puzzle is thinking beyond individual events or even individual contracts. Aim to cultivate a long-term relationship with the unions connected to your venue. That means keeping dialogue open even in off-season or when you’re not in the middle of a show. For example, invite union leaders to your venue’s end-of-year holiday party or to an open house event. Send a congratulatory note if you hear the union business agent got re-elected or if a prominent union member retires after long service. These human touches outside of the immediate work grind create goodwill. Some venues partner with unions on community service – like jointly hosting a charity drive or participating in a career day for technical trades. It shows you’re both invested in the local community and on the same side in those efforts.

When contract negotiation time comes (usually every few years the CBA is renegotiated), you’ll be glad if you’ve laid this groundwork. Negotiations can be tense by nature (wages and terms are at stake), but if the overall relationship is strong, it’s much easier to negotiate in good faith and reach an outcome that works for both. You might even get more flexibility or operational concessions in the new contract because the union trusts the venue not to abuse them. For instance, they might allow a pilot program of a venue hybrid streaming crew (mix of union camera operators and non-union IT personnel) to support your new digital audience offerings, whereas a union with a chip on its shoulder would reject anything atypical out of hand. Building trust literally pays off in innovation and efficiency.

Remember that today’s union crew could be tomorrow’s full-time staff or biggest fans of your venue. There are plenty of cases where union stagehands later take on venue management roles, or where they become the institutional memory that trains generations of newcomers. Treat them with the respect you’d give a valued colleague or mentor, and they often reciprocate with loyalty and dedication that goes beyond punching a clock. When venue operators speak of crew family, it usually includes those union brothers and sisters who have been hauling cases and flying scenery at that venue for 20–30 years. In the end, that’s the ideal state: union crew and venue management working together so closely that to outsiders it’s indistinguishable – it’s just one big crew making the magic happen.

By embracing compliance as a baseline and harmony as a goal, you transform union labor from a source of stress into one of your venue’s greatest assets. After all, when every member of your crew – irrespective of union status – is motivated, heard, and aligned, the results show up in flawless events, controlled costs, and repeat business. Now, let’s wrap up with key lessons from this discussion.

Conclusion: Embracing Unions as Partners in 2026

Working with union labor at venues doesn’t have to be an adversarial or bewildering experience. As we’ve explored, it comes down to knowledge, planning, and people skills. Venues that thrive in 2026 are those that treat unions as partners, not obstacles. Compliance with contracts and labor laws is your foundation – it keeps you out of trouble and builds trust. On that foundation, you can optimize costs by smart scheduling and honest budgeting, avoiding nasty surprises by expecting the expected (overtime, breaks, etc.). And with a solid plan and clear rules in place, you’re free to focus on crew harmony, turning a diverse group of union and non-union workers into one cohesive team.

What does success look like? It’s stagehands who take pride in their work and your venue, because they feel respected and fairly treated. It’s non-union staff who welcome the union crew load-in day, because they know they’ll learn a trick or two from seasoned pros. It’s a backstage that’s calm, professional, even friendly – rather than tense with “us vs. them” vibes. It’s being able to pick up the phone and call the union business agent to brainstorm how to handle an unusual event requirement, rather than only ever talking when there’s a problem. It’s having confidence that when the house lights go down and the show starts, every spotlight operator, sound tech, rigger, and usher is giving their all to make it a success, because they feel like stakeholders – not hired hands.

In 30+ years of venue management, veteran operators have seen both sides: venues that fought their unions and struggled, and venues that embraced union labor as a cornerstone of their excellence. The latter is the model to emulate. Live events are unpredictable – you need your crew’s goodwill when a curveball comes. If you’ve built a cooperative environment, union crew will go the extra mile when the show is on the line. They’ll stay late to fix that last-minute issue (knowing you’ll pay them fairly for it), they’ll adapt roles to cover an unexpected gap (knowing it’s a team effort), and they’ll present a united front with you to visiting productions that “this is how we run a world-class venue.” That kind of crew unity and professionalism becomes a selling point for your venue.

As you navigate compliance, costs, and crew dynamics, remember that at the end of the day it’s all about humans working together. Unions are simply a framework to ensure those humans are treated well – which is exactly what you as a venue operator want too, if you aim for longevity and success. By demystifying the rules and investing in relationships, you demote the “union issue” from a storm cloud to just another part of the business you manage with confidence. The payoff is smoother operations, predictable budgets, and shows that wow audiences without backstage drama. In the live events world, when the crew is happy, the artists are happy, and the fans are happy – and that is the ultimate goal.

Before we close out, let’s recap the most important takeaways from this guide.